Perspectives in Cinema

Translated Screams

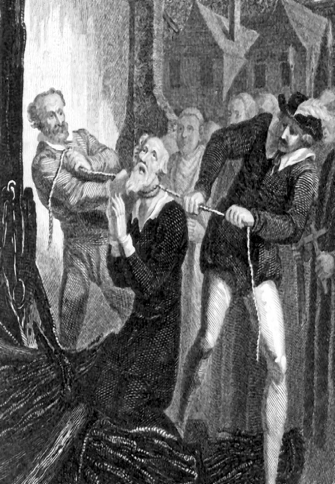

Translating culture is a pursuit that carries with it a terrifying history—on October 6th of 1536, in the town of Vilvoorde, just north of Brussels, British scholar, William Tyndale was betrayed, imprisoned, suffocated, and burned at the stake. The crime that led to his brutal execution? Translating the Bible from Greek to English, and in doing so, delivering a counter punch to Pope Paul III’s Catholic foothold on Europe. Tyndale was not alone in his rebellion or punishment. Almost two hundred years before him, the Czech theologian and Roman-Catholic priest, Jan Hus committed himself to a new interpretation of Biblical philosophy that led to a Bohemian reformation and staggered denominations upon Christianity in addition to sparking accusations of heresy that no doubt assured his execution. In fact, these apocryphal instances of brutality in the vain of God could inspire their own horror film franchise, and almost 500 years later Hollywood carries on the tradition of marrying fear and translation.

Translating culture is a pursuit that carries with it a terrifying history—on October 6th of 1536, in the town of Vilvoorde, just north of Brussels, British scholar, William Tyndale was betrayed, imprisoned, suffocated, and burned at the stake. The crime that led to his brutal execution? Translating the Bible from Greek to English, and in doing so, delivering a counter punch to Pope Paul III’s Catholic foothold on Europe. Tyndale was not alone in his rebellion or punishment. Almost two hundred years before him, the Czech theologian and Roman-Catholic priest, Jan Hus committed himself to a new interpretation of Biblical philosophy that led to a Bohemian reformation and staggered denominations upon Christianity in addition to sparking accusations of heresy that no doubt assured his execution. In fact, these apocryphal instances of brutality in the vain of God could inspire their own horror film franchise, and almost 500 years later Hollywood carries on the tradition of marrying fear and translation.

Since the first decade of the 21st century, American cinema has made concerted efforts to gobble up international features and existing properties, but how does its translation of international horror coordinate Hollywood on the X-Y axis between culture and industry? And what does the onscreen representation of women in the nightmare world tell us about our female gaze?

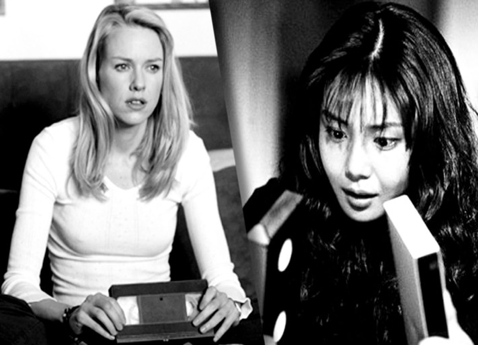

Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002) is a Hollywood stab at Hideo Nakata’s Japanese horror mystery, Ringu (1998). Originally adapted from Koji Suzuki’s novel, the movie is a freaky fable that follows an investigative reporter and her ex-husband as they track the haunted bread crumbs of an enigmatic video tape that curses its viewers. After watching the tape, audiences are doomed to die in a seven days. High concept, no doubt, but both the American and Japanese versions have found not only critical satisfaction but a financial success that continues to balloon; the American re-make established an audience and inspired two sequels, the most recent being the not-so-cleverly titled Rings in 2017.

In his Forbes review of the movie box office for the weekend after Rings’s release, Scott Mendelson reminds us that “Gore Verbinski’s The Ring was an absolute horror sensation in 2002 ($129 million from a $15m debut weekend and $248m worldwide on a $48m budget).” But The Ring‘s financial success was just the slope of the iceberg, considering American audiences received the film so well that the film is credited for kick-starting a renaissance of horror features, re-makes, and franchised screams that, like the British Invasion of mid-sixties rock ‘n’ roll, reinvigorated its genre.

Ringu floats along with a pace that is more reminiscent of a foggy noir nightmare, where the Hollywood version streamlines the horror and takes quicker breaths. Verbinski concerns himself less with mood than with special effects that liken a haunted house shock-and-awe experience. Certainly pace can flirt with ideas of culture and lifestyle, but it is the deviation in character that is particularly telling. Both versions deal with a broken family at the nucleus of a haunted house story. Mama bear love and paternal guilt tug at the parents in both movies; however it is the characterization of the father figure that reflects a glimpse of cross cultural ideals and expectations.

Ryuji, the father in the original, starkly contrasts his fictional American counterpart, Noah (Martin Henderson). Noah is a rogue photographer whose streak for individualism embodies an American prototype and leaves him too charmingly arrogant to wear the traditional necktie of fatherhood. Ryuji is a workaholic, and his stiff commitment to his academics sculpts a Japanese cliché and shines a light on struggle for Japanese parenthood. And in both versions, these paternal figures are killed-off for their failures. Or perhaps, they were simply in the way of a good horror movie kill.

Final sequence of The Ring. Martin Henderson doesn’t exactly die with his boots on.

And since we’re at the ending, let’s talk about it: Verbinski’s version broke the American mold of horror in part to remaining faithful to Ringu‘s ending. Normally, American horror ends its stories by extinguishing the source of horror completely. See King Kong (1933), The Blob (1958), and The Excorcist (1973) for examples. In short, the monster dies in America, but Japanese horror endings linger like atomic fallout.

Nakata serves up a healthy dose of anti-resolve in a final plot thread that leaves daddy dead and mommy with the discovery that the cursed tape allows its viewer to live if-and-only-if they copy the tape and copy the curse. It’s a story hook that kindles fear, fuels franchise investments, and speaks sequels for Hollywood’s love affair with foreign horror re-makes.

Takeshi Miike echoed the Ringu to similar results with Chakushin Ari (2003). Similar to Ringu, Miike’s movie deals with fear of death and perhaps a fear of technology. Here are the particulars: people begin to hear voice messages from themselves as they are dying. Sound like Ringu? Its results were similar as well, and if you’re thinking it sounds like that Ed Burns movie you caught on T.V. the other night, you’d be right. Hollywood translated Chakushin Ari into One Missed Call in 2008.

Takeshi Miike echoed the Ringu to similar results with Chakushin Ari (2003). Similar to Ringu, Miike’s movie deals with fear of death and perhaps a fear of technology. Here are the particulars: people begin to hear voice messages from themselves as they are dying. Sound like Ringu? Its results were similar as well, and if you’re thinking it sounds like that Ed Burns movie you caught on T.V. the other night, you’d be right. Hollywood translated Chakushin Ari into One Missed Call in 2008.

Many other re-makes could be mentioned, but some of the most notable titles include Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish vampire flick, Let the Right One In (2008) which was reborn into Let Me In (2010) under the direction of J.J. Abrams collaborator, Matt Reeves. Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-on (2002) cannot be ignored; also hailing from Japan, the remorseless ghost story paved way for a second Japanese film, Ju-on: The Grudge (2003) and was shadowed by two more American Grudges, the second in 2006 and the third in 2009.

Similarly, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo franchise was a smash hit before and after Hollywood snatched up the story. After the original Swedish film by Niels Arden Oplev enthralled movie-goers in 2009, Hollywood A-list director, David Fincher, captured the story within his frame. Spike Lee too looked abroad in 2013 and converted Chan-wook Park’s nightmare-fueled tragedy, Old Boy (2003), for American viewers. A noble effort in a corrupt cause, perhaps, but another example of the overseas inspired trend.

From a financial angle, it’s no surprise that Hollywood investors would piggyback their way to the bank with an entertainment package that had proven its worth in the international arena. Existing properties are proven markets. Let’s consider the case of the film geek that saw Ringu and is soured at the news of the Hollywood re-make. Guess what? He’s going to buy a ticket because geeks might rant and rave about minutia, but at the end of the day they’re dollar signs to Hollywood investors.

It’s just good business, and horror isn’t a lone wolf when it comes to the remake game. The Korean crime thriller, Infernal Affairs (2002), became The Departed (2006), which earned Martin Scorsese an overdue Oscar win for best director. You can add the Al Pacino/Robin Williams thriller, Insomnia (2002) to the list. Based on the Norwegian film of the same title, its narrative orbits around the murder investigation of a local teen. And before that, you have the highly undervalued and under-seen Kurt Russell creeper, The Vanishing (1993), began as the Dutch language film, Spoorloos (1988), just five years prior—and the index rolls on: True Lies (1994), The Talented Mr. Riply (1999), Vanilla Sky (2001) , Passion (2012), and Ghost in the Shell (2017) are a few American titles that all owe their existence to foreign studios and audiences.

It’s just good business, and horror isn’t a lone wolf when it comes to the remake game. The Korean crime thriller, Infernal Affairs (2002), became The Departed (2006), which earned Martin Scorsese an overdue Oscar win for best director. You can add the Al Pacino/Robin Williams thriller, Insomnia (2002) to the list. Based on the Norwegian film of the same title, its narrative orbits around the murder investigation of a local teen. And before that, you have the highly undervalued and under-seen Kurt Russell creeper, The Vanishing (1993), began as the Dutch language film, Spoorloos (1988), just five years prior—and the index rolls on: True Lies (1994), The Talented Mr. Riply (1999), Vanilla Sky (2001) , Passion (2012), and Ghost in the Shell (2017) are a few American titles that all owe their existence to foreign studios and audiences.

Undoubtedly the prospect of an English language re-make is a tempting fruit; one that Michael Haneke is no stranger to. By his own volition, the celebrated filmmaker undertook the task to translate his very own Austrian film, Funny Games (2017). Katey Rich incorporates her unique vantage point on the re-make in her interview with Haneke at CinemaBlend.com:

[He] has chosen to remake his 1997 film, Funny Games, shot-by-shot; the only difference is the actors, all English-speaking, and the location, which is pretty much exactly the same as the first one. The concept, of course, is identical: A rich family in their vacation home is taken hostage by two young men, who embark on a series of “games” with the family that all end in torture, humiliation, and death. But this isn’t the “torture porn” you’re used to, oh no. The moment one of the killers looks into the camera and winks, you know you’re in new, highly experimental territory.

When Rich asks Haneke directly about the remake, his response indicates precision in translation. He explains, “I didn’t have to add anything, and just to change it a little bit I thought was dishonorable. If at all, it became almost a gamble with myself, whether I was able to do the exact same film under very different circumstances.”

So translation and shared stories makes sense artistically and financially; in the case of the Ringu movies and so many foreign horror remakes, we see that fear is familiar and screams are part of a universal language, but beyond the politeness of cross cultural business banded by money and within our American gates, horror movies are addressing the country’s differences.

When nightmares resonate in mass appeal (read: ticket sales), the bad dream might be more telling than meets the eye. Flip back the calendar half a century, and you’ll discover George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead to be one of the most confrontational horror films of the year—a story that parallels the claustrophobic paranoia of a 1968 America that was turning in on itself amidst its incendiary struggle for Civil Rights and equality in sex and nomenclature. Gutsy and subtle in the same stroke, its release follows the assassinations of RFK and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Romero’s shoe-string landmark shocked audiences with imagery that presents: 1) an unusual brand of slow moving, eternally gluttonous zombies; and 2) an black hero who, after surviving a mob of ghouls, is thoughtlessly shot between the eyes by redneck law. As grim as an ending could be, Romero puts his audience through the ringer, and after all the blood, sweat, and more blood, he tells us in 1968 that it’s not going to be okay. At least not for a while.

And if Romero was telling us the brawl for racial equality won’t be an easy fight, contemporary horror movies are echoing his call and telling society that it’s still not okay. And he was right—racial tension in America is higher than has been in recent memory, and all the while modern monster movies are getting in your face about it, just as society as is getting in each other’s face about it.

And maybe that’s progress. Just like a spat in your personal life, sometimes problems are addressed with whispers before shouts, and it’s not until the fight reaches its zenith that tensions can begin to resolve. So maybe shouting is better than politely holding tongues. Horror movies might be suggesting the same, and the genre is shifting its reaction to the struggle of inequality from soft spoken subtlety—as in Night of the Living Dead’s zombie metaphor—to a roar, most popularly exemplified by Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). The surprise hit is a socially conscious film that sold the hell out of some popcorn and wears its heart on its sleeve. The horror mystery tells the story of an affluent white community who kidnaps black men to snatch their bodies and transplant their aging consciousness into young, able bodies, a premise is as imaginative as it is unapologetic.

And maybe that’s progress. Just like a spat in your personal life, sometimes problems are addressed with whispers before shouts, and it’s not until the fight reaches its zenith that tensions can begin to resolve. So maybe shouting is better than politely holding tongues. Horror movies might be suggesting the same, and the genre is shifting its reaction to the struggle of inequality from soft spoken subtlety—as in Night of the Living Dead’s zombie metaphor—to a roar, most popularly exemplified by Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). The surprise hit is a socially conscious film that sold the hell out of some popcorn and wears its heart on its sleeve. The horror mystery tells the story of an affluent white community who kidnaps black men to snatch their bodies and transplant their aging consciousness into young, able bodies, a premise is as imaginative as it is unapologetic.

Before Get Out, the terror thriller, Green Room (2015) set America’s racist underbelly as a source of horror in a plot that captures a young and carefree punk band, in a neo-Nazi venue where they witness a murder that makes them a liability. The Purge: Election Year suggested the danger of class-system animosity in a national holiday of bloodthirsty catharsis to design the story’s foundation. In her article for vox.com, Aja Romano tells us that “the home-invasion trope has been part of cinema since cinema has existed… [and] metaphorically, the allegory of the modern home invasion film is all about the sanctity and deceptive sovereignty of America as a nation state, powerful and impenetrable.” This of course smacks of fears rooted in post 9/11 terrorism and immigration—and cinema’s reaction is to punch the proverbial bull shark in the nose.

Before Get Out, the terror thriller, Green Room (2015) set America’s racist underbelly as a source of horror in a plot that captures a young and carefree punk band, in a neo-Nazi venue where they witness a murder that makes them a liability. The Purge: Election Year suggested the danger of class-system animosity in a national holiday of bloodthirsty catharsis to design the story’s foundation. In her article for vox.com, Aja Romano tells us that “the home-invasion trope has been part of cinema since cinema has existed… [and] metaphorically, the allegory of the modern home invasion film is all about the sanctity and deceptive sovereignty of America as a nation state, powerful and impenetrable.” This of course smacks of fears rooted in post 9/11 terrorism and immigration—and cinema’s reaction is to punch the proverbial bull shark in the nose.

In addition to race, horror continues to address equality among gender. As Beth Younger points out in her article for Quartz.com, movies have men speaking twice as much as women with exception of one genre: you guessed it, horror. Seeing women in danger is certainly a fetish that male horror filmmakers have brought to the social consciousness (for examples see just about every Hitchcock film ever made and the multitudes of films that were inspired by them), and so it is no surprise that ladies often lead these stories, but does this tell us more about our fears or our desires?

In addition to race, horror continues to address equality among gender. As Beth Younger points out in her article for Quartz.com, movies have men speaking twice as much as women with exception of one genre: you guessed it, horror. Seeing women in danger is certainly a fetish that male horror filmmakers have brought to the social consciousness (for examples see just about every Hitchcock film ever made and the multitudes of films that were inspired by them), and so it is no surprise that ladies often lead these stories, but does this tell us more about our fears or our desires?

Younger asserts that “the genre has moved from taking pleasure in victimizing women to focusing on women as survivors and protagonists” and lists titles such as Jennifer’s Body (2009), The Conjuring (2013), and The Witch (2015) as cases of point.

One of the great opportunities of foreign-film remakes is the ability to juxtapose. Is America’s progress part of the progress of the world, or is the country on its own timeline? Looking at 2017 alone, several titles are making waves for female representation—Die Holle (Cold Hell), an Austrian film that exposes the horrors of a woman cab driver, who must stand up to sexual aggression. She eventually embarks upon a search for a serial killer who targets female sex workers of the Muslim faith. Another title, Revenge, shares a similar theme. Our leading lady’s rape serves as the catalyst for this revenge movie that promises as much survival as vengeance. South of the border, Tigers Are Not Afraid serves as another germane example. The Mexican suspense flick trails a young girl with strange visions who survives her mother’s murder and navigates a slum surrounded by sex trafficking, dope zombies, political corruption, and gang violence. The twisted fairy tale is written and directed by Issa Lopez and is brimming with depth and imagination.

One of the great opportunities of foreign-film remakes is the ability to juxtapose. Is America’s progress part of the progress of the world, or is the country on its own timeline? Looking at 2017 alone, several titles are making waves for female representation—Die Holle (Cold Hell), an Austrian film that exposes the horrors of a woman cab driver, who must stand up to sexual aggression. She eventually embarks upon a search for a serial killer who targets female sex workers of the Muslim faith. Another title, Revenge, shares a similar theme. Our leading lady’s rape serves as the catalyst for this revenge movie that promises as much survival as vengeance. South of the border, Tigers Are Not Afraid serves as another germane example. The Mexican suspense flick trails a young girl with strange visions who survives her mother’s murder and navigates a slum surrounded by sex trafficking, dope zombies, political corruption, and gang violence. The twisted fairy tale is written and directed by Issa Lopez and is brimming with depth and imagination.

Looking back at Ringu—we can see the film chips away at patriarchy. The Japanese adaptation of the novel makes a significant revolution. It moves the protagonist from a married male to a divorced, single mother, which allows the conversation of female representation to develop. The American remake does the same, providing audiences with a heroine that on one hand takes charge of her career, but on the other hand, cannot be excused from her maternal duties. It’s a realignment of female identity in the horror tradition, but Verbinski’s American stab takes a step backwards. The Ring shows Rachel to maintain a resentment of motherhood, a conservative oversimplification of the work-family tight-rope that a single mother must balance. In her introduction scene, she’s both vulgar and glib to her son’s needs. As the story continues to build, Rachel’s parental flaws and her ex-husbands role in the film and family suggest the need for a paternal presence.

While the American film remains more conservative than its Japanese predecessor, both versions play into an genre evolution that presents women as survivors rather than objects of sex and violence. There’s no doubt that the movie world is offering opportunities for female perspectives throughout culture, but with new seasons of cinema upon us, the question of whether the world wants to hear these stories will soon be answered.

As for the dollars—they might tell you more about marketing packets than they do about the movies, but the movies themselves? They tell us everything. They tell us about our hopes, dreams, and nightmares. They shows us at our most primal and at our most civil. At our strongest, and at our weakest. They show us how we hate, and they show us how we love, and most importantly, they shows us how we do both.

The inescapable truth is that cinema’s influence on itself remains somewhere between chronic and incestuous, but with such a rich history of tossing stories back and forth across the proverbial pond, it’s safe to say that humanity has found more in common with each other than just ticket sales. So in an era of Hollywood that is plagued with sexual predators, cultural misrepresentation, and embarrassingly unequal pay and opportunity for women, there is still some slashing to do get to the root of the American disease.

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Companies

Social Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

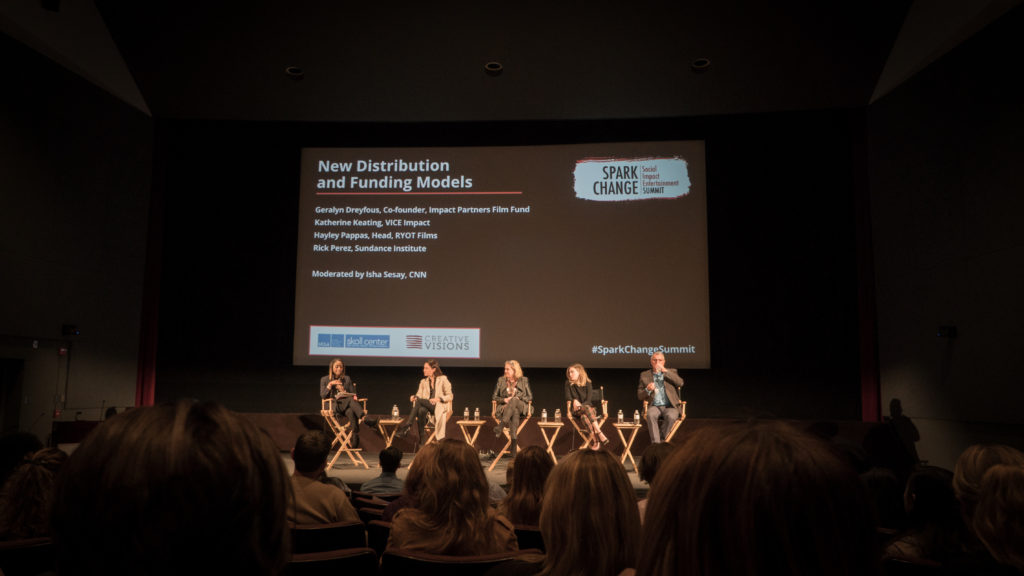

“Social impact entertainment’s time has come,” Teri Schwartz, the dean of UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television said as she welcomed everyone to the first Skoll Center summit. Nonprofit leaders, social campaign strategists, experts in distribution and funding, and a variety of creators gathered to define social impact entertainment, learn more about storytelling, and discuss new distribution and funding models.

Students and professionals alike joined in the conversation thinking about questions like: Is intention enough? What is the difference between storytelling and advocacy? What are examples of previously successful social impact campaigns and how can we follow those models? In this time of mass streaming platforms, how can artists market their social impact content and demand awareness?

The social impact entertainment field is developing, but very much alive. However, unlike industries that sometimes hide information to maximize self-growth, it is critically important for us to collaborate in this space and build a community of entertainment activists. Cinema of Change sent several to this summit to do exactly that: share what we’ve learned and be honest about what we don’t know yet.

So, what’s the secret sauce? How can films change the world?

Truth is, like the entertainment industry itself, there is not one path to ending climate change or human trafficking through film (unfortunately, I know). However, whether it is documentary, narrative, or docu-fiction, everything begins with storytelling.

-

STORYTELLING

No matter how important the statistics are or how beautiful the production design is, people are not going to watch a film that has no story. Sometimes, that is why a narrative film may even have a larger impact on a social issue than a documentary film because people relate and empathize to the fictional characters more and will walk away with those emotions in mind.

Holly Gordon, Chief Impact Officer of Participant Media: There’s a difference between storytelling and advocacy. Storytelling comes 100% from intention, but also creativity. “Creativity means intention and the ability to tell a story.” And that’s what leads to transformational change, which is long-term and visionary, compared to transactional change.

Hayley Pappas, Head of RYOT: As a reminder, “It doesn’t always have to be heartbreaking to be transformative. You can laugh a lot and see something in a new way.”

Davis Guggenheim, director of An Inconvenient Truth and He Named Me Malala: “Without the intention, you’re not going to do it. It’s too hard.” Documentaries can hit a wall sometimes because everyone working is so passionate about the topic, but when you go into the editing room, there’s no story.

As much as we support documentaries here at Cinema of Change, we also believe that mega blockbusters and social impact are not mutually exclusive. In fact, we wrote an article on exactly why we think the opposite here.

Darnell Strom, Creative Artists Agency: “Story matters. Representation on screen matters and that has a ripple effect.” Sometimes, filmmakers may not set out to have a specific intention, yet organic social issue campaigns arise from a great story. Take Black Panther for example. Disney probably did not set out to create a transformative piece about black culture through a Marvel comic book story, but the film had a majority black cast and depicted a woman leading the technological developments. Now, nonprofits are jumping up about women in STEM and young black boys and girls can watch the film and be like, Hey, if someone who looks like me can do it, so can I.

-

MEASURING SOCIAL IMPACT

Great, this film tells an incredible story about a disadvantaged youth rising from poverty and attending a prestigious university, but how do we measure the social impact? In other terms, how do we calculate the number of minds changed, or decisions made to take action? Even Gordon agreed that transformational change is very hard to measure, but it can be done.

Holly Gordon: For Girls Rising, which is both a film and nonprofit about the importance of educating young girls, measurement meant hiring Mission Management to analyze impact in three ways: changed minds (reach), changed lives (money raised), and changed policy (shifts in government policy). Gordon worked on relationship building with a number of nonprofits and even leaders like Michelle Obama to develop impact partnerships and shape campaigns around the themes in the documentary, before a single frame was even shot.

Rory Kennedy, director of Last Days in Vietnam and Ghosts of Abu Ghraib: Social impact is often thought of in large numbers: raising millions of dollars, changing thousands of lives, but it is also just as important on an individual level. For example, in Last Days in Vietnam, Stuart Herrington, a counterintelligence officer in the Vietnam War, was responsible for safely evacuating American soldiers at end of the war, but he knowingly left 422 Vietnamese soldiers there despite promising them safety. At the premiere of the documentary, Harrington reflected on his guilt and regret for leaving all those lives behind and said that he dreaded ever meeting one of the 422. Sure enough, one of the Vietnamese soldiers Harrington left walked up on stage and told him, “I forgive you.” That moment left both of the men in tears and it may not have changed a hundred lives, but it changed two.

-

IMPORTANCE OF SOCIAL IMPACT CAMPAIGNS

When a film wraps, the awareness and campaign work most definitely does not. Social impact campaigns are critical to accelerating awareness and creating a sustainable, lasting effect. They’re arguably more effective when launched before the film even begins production.

Bonnie Abaunza, founder of The Abaunza Group which has launched campaigns for The Hunting Ground, Hotel Rwanda, Cries from Syria: These impact campaigns are designed to intersect all industries and companies. Impact comes from educating students, mobilizing ambassadors, challenging companies, and partnering with nonprofits and policy leaders who care. One example of a highly successful social impact campaign is the one for Blood Diamond. Lena Khan, the director of The Tiger Hunter, even told Abaunza that she has a conflict-free diamond on her hand because of the film. Jewelry companies like Tiffany & Co. joined the movement by labelling their diamonds as “conflict-free” especially because more and more people started asking about it. Amnesty International created an entire curriculum to introduce the issue to students.

Ted Richane, Vulcan Productions Impact and Engagement: At the end of the day, “We can have our strategies, but the best thing we can do is listen. The community is awesome and going to be inspired and go to take the issue upon themselves.” That’s the ultimate goal, right? Launch the campaign, tell the story, and empower others to share and do something about it all.

-

DISTRIBUTING AND FUNDING SOCIAL IMPACT FILMS

The world of distribution and funding can be quite daunting to enter, because no matter how passionate someone is, it is always difficult to get the money needed to transform passion into action. Major companies are also a huge part of the conversation. How do they decide what films to green light? How can indie artists break out with both an entertaining film and one that creates change?

Geralyn Dreyfous, Co-founder of Impact Partners Film Fund: There is a shift nowadays in the distribution world. Only two films sold at Sundance this year. Netflix is commissioning their own content. Companies are not paying their creators enough, especially for short form content. To the artists: “You love it so much, you’d do it for free. But you have to stop doing it for free.” When starting out with trying to find investors, you can always pitch to the Impact Partners Film Fund, but if you’re not successful there, think about incentives and break up your budget into smaller chunks for financing. Can you give donors credits, on screen thanks, private screenings, and other benefits? “Mostly, founders are interested in amplifying and aligning your content with their philanthropic goals. They need to know that you’re the person to tell that story.”

Katherine Keating, Vice Impact: With a cross-platform company like Vice, it’s very important to think about who the audience is and where they are consuming their content. Some things are meant to be a series of five 1-minute shorts on Facebook, even though the artist may have pitched it as five 1-hour series. Another way to integrate the impact campaign is through brand partnership with large, respected companies. For example, Colgate, one of the biggest toothpaste sellers, is now promoting water conservation and looking at ways to reduce plastic use in their packaging. Companies are starting to recognize the importance of social impact and it’s our job as their commercial creators to push them in that direction.

Cinema of Change previously interviewed entertainment attorney Mark Litwak about the “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution”; read what Litwak has to say here.

NOW WHAT?

“To create in this chaotic world peace, to seek in this gathering darkness light, to transform the hatred into a new kind of loving. Together, we can transform this world. It’s going to be really hard. But we can do it, and it will be through storytelling and courageous people like you.” (Kathy Eldon, Co-founder of Creative Visions). With that, the SPARK CHANGE Social Impact Entertainment Summit came to end, but our work is just beginning.

As audiences, we have to demand for content that does not further marginalize communities and perpetuate stereotypes.

As companies, we cannot stay silent to the injustices in our world in order to protect our brand.

As filmmakers, we are not just producing beautiful, cinematic pieces. We have the responsibility to use those creations to spark change.

—

List of all organizations in attendance: Cause Cinema, CNN, Creative Activists Network, Creative Artists Agency, Creative Visions (co-host), Google, I am Jane Doe, Impact Partners Film Fund, Living on One, Majority Film, Participant Media (sponsor), President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities, RYOT, Skoll Center (co-host), Sundance Institute, The Abaunza Group, Vice, Vulcan Productions (sponsor) UCLA School of Theater Film Television

*Sayings in quotation marks are directly quoted. Other remarks are paraphrased.

Media Impact

Mr. President…

The character of a president matters. And in this past year since Donald Trump was elected, many of us wished for a president who displays more character, humanity and self control. We want our president to be someone who we look up to and who is the moral leader of our country and who reflects the best of our American values. Donald Trump has fallen far short.

As an electorate we might be more excited this year if Jeb Bartlet, Andrew Shepherd or Dave Kovic had been elected president. Who are they?

They are three of the most popular Presidents of all time. At least that’s what critics and the public thought. They are Presidents from popular films and television, “The West Wing”, “The American President” and “Dave”. They are Presidents that we loved and admired for their humanity from the moment we met them. Unfortunately, they were all on screen and not in the Oval Office.

Why do we love these TV and film Presidents? It’s because they display a humility and basic connection to the human experience that our politicians do not.

In “Dave” an ordinary man with the desire to help his fellow man suddenly finds himself in the oval office, impersonating the President after the real President dies while having sex with a staffer. It is the “ordinary man” quality that endears us to Dave Kovic as he tries to fill the President’s shoes. He steps into the presidency with no agenda other than to try and do his civic duty, but when he discovers he’s being used by dark political forces, he does what his heart tells him to do and strives for policies that benefit ordinary people like himself. We love this President because he is literally one of us. We root for him because he is the Everyman. “Dave” is a modern day fairytale for sure, but we love it because it fulfills our wish for what we want in a President. For him to be us.

In “The American President” President Andrew Shepherd is a widowed President who falls in love again and starts dating during an election year. This President goes after the person he loves despite all odds and at great political sacrifice. In doing so, he rediscovers his passion for why he wanted to be President. It’s love that guides him to do the right thing over political expediency. We hope always that our Presidents act in the best interest of the people and not politics, but that isn’t always the case. In this film, this President does and we cheer him for it. We also see a President awkwardly asking out a woman and dealing with issues of sex, dating and being a single father. These are relatable issues. In this film, the President is humanized, shown a man first and a President second.

Finally, Jeb Bartlett in “The West Wing” embodies the frailties and flaws of a human being as he navigates his presidency. He loses his temper often. He is loyal to a fault. We see him attend sessions with a psychiatrist. He hides his MS from the American people. This is a President who is humanly flawed on many levels and we care about him, because he carries on and does so out of a noble ideal about public service. But what humanizes him the most is what is broken about him. We all feel broken in many ways and want our leaders, our President to show us that they are not automatons, but flawed, breakable human beings… like us.

These three Presidents were created by filmmakers who could shape their characters to be who they wanted them to be, but for the most part the writers and directors who gave birth to these Presidents really shaped them to be who we wanted them to be. They gave us Presidents that rose to our expectations for humanity, Presidents with a moral compass, Presidents we would want to see in the Oval Office. But where does that leave us in the real world? Where does that leave us with November 8th?

I think that into today’s world with a 24-hour news cycle, cameras recording every moment and internet scrutiny of every aspect of a President from physical appearance, to stumbles in words and on carpets, it’s hard for a President to live up to expectations. Look how well President Obama hid being smoker, only lighting up his cigarettes out of camera view.

How would great Presidents of the past fair in today’s world? Would JFK with his many affairs and prescription drug addictions survive the media scrutiny? FDR served as President from a wheel chair and lead us through World War Two with most of America not knowing he was disabled. They only heard his voice on the radio or saw photos in which he was standing. This only reinforces how much more we know about our Presidents today. Every aspect of their life is scrutinized.

So I ask the question… Are our candidates today really worse human beings than Presidents of the past, or do we just know much more about them and therefore see all their flaws? If that’s the case, then why do we love our movie Presidents for their flaws and dislike our current President for his? I think the answer is quite simple. One is a movie and one is real life. And in the movie, the writer can craft redemption and character growth, something that Donald Trump will likely never achieve. We should hold our Presidential candidates to a much higher standard and we should hope to find candidates that aspire to the ideal we admire in our movie Presidents.

I hope our next President rises to the level of humanity, basic decency and noble purpose that we see in our movie Presidents. We should expect it. We should seek it and we should never set the bar lower to accommodate someone not willing to be the leader we require.

Real life needs heroes and role models too.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

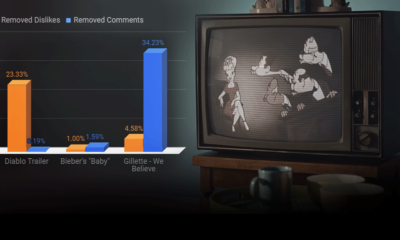

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films