Filmmakers

YouTube of Change

What are we to make of events that reach us in the form of a video clip of a police shooting that is sandwiched by both a relative’s baby pictures and today’s third unanswered invitation to a comedy show? Why are we so entranced by the no-holds-barred, oft-anonymous and rarely satisfying debate over the video’s causes and significance in the comments section? Does the way in which news is consumed by anyone who spends more than a few minutes a day online seem a little…schizophrenic to anybody else?

As your author I apologize for starting us off on this topic with a stumble, but I would rather fall before reaching the cliff’s edge, and “The News” today is nothing if not treacherous. Events of profound and systematic violence reach the eyes of millions across the globe in a simultaneous and visually identical format due to two main factors: most of the inhabited world can be filmed at any time, greatly due to cell phones, and most of the world’s population can access these images via the Internet. Millions join the public debate with written responses often as vicious as they are consequence-free thanks to the safety blankets of anonymity and groupthink. Print media are less popular than vinyl records, leaving the door open for hundreds of websites staffed by armchair journalists to scour the Internet until a police shooting, or an atrocity in the Middle-East is filmed and uploaded. With such competition there is little time for the reporter to develop an opinion before they must share it with the world.

Docs can make a big impact through simple presentation of their subject, like the opening of “Blackfish” here…

It does seem that we are all riding a wave of interest in seeing and hearing the woes of the world, not only out of curiosity but because acknowledging a problem is the first step towards fixing it. The fact is that amateur videos presented as news are a powerful source of public truth whether they deserve to be or not, and the rate at which every single one of us consumes them tends to prevent their careful examination. To be sure our fellows in print media (both analog and digital) and academic journals deserve credit for their work in uncovering the background of, say, endemic police brutality against people of color. It’s just that filmmaking at its core is sensational; it is a multi-sensory, captivating experience that works very closely with the subconscious mind. As professional filmmakers I hope that we can remind audiences that they have a choice to form opinions on a subject by watching something that is skeptical, logical, and built upon careful examination.

…or they can create a gripping story by employing scripted effects, such as what was done with these “The Jinx” reenactors.

Jonathan Mahler’s NY Times article from March 22, 2015 provides a succinct explanation of what may be socially-conscious cinema’s biggest saving grace in the Internet Age: bringing hard news to an audience while also entertaining them. Mahler’s case in point is the recently concluded HBO series The Jinx, which profiles murder suspect Robert Durst and now-famously ends with what could be his accidental confession. Was it disingenuous for the creators of The Jinx to hold their bombshell revelation until the last minute? I can only imagine what the families of the victims would answer, but the fact is that Durst’s arrest was probably inevitable from the moment the show was recorded. Mahler mentions several other recent docs that have helped lead to observable social change including Blackfish and The Invisible War. For a time the reports of criminal negligence in Blackfish contributed to SeaWorld’s declining stock value, and The Invisible War was instrumental in changing the U.S. Military’s investigation of reported rape. What they have in common are truly risky ideas and footage in a wrapper of shocking drama and excitement.

That is not to say Inside Job did a better job of reporting the 2008 financial crisis than a Huffington Post reporter simply because it is a thriller; a collection of articles spanning several years likely tells a similar story. One source’s opinion, however, is vastly more likely to become white noise in our constantly upgraded, push notification-dependent lives. Even with the proliferation of video platforms it is far less likely that the average viewer will be overwhelmed with films on a given subject. There will probably not be a Blackfish 2, nor a counterargument that is nearly as successful. The reasons for the uniqueness of films are largely financial and technical, of course, but filmmakers should still recognize that they nearly have a monopoly on long-form journalistic content these days.

Do I cry foul then that technology has made it so that any schlub with a cell phone can garner millions of views online and appear on MSNBC as a citizen-hero while producers who spend years making a well-researched, subtle exposé of societal ills are lucky if they don’t have to mortgage the house to finish? It’s tempting. However, what strikes me as the crux of the issue is that there appears to be little interaction between amateur and professional filmmakers. Opinions are formed (or reinforced) on the daily whenever a person watches a couple minutes of racist Oklahoma fraternity chanting on CNN.com at work, and ends the day with a Netflix viewing of The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975. Is it possible that the two information networks can collaborate and (pardon the pun) reach a kind of all-encompassing happy medium?

The example I would like to leave you with is one that should be familiar to Bay Area residents: 2013’s drama Fruitvale Station, about the shooting death of Oscar Grant at the hands of BART police in the early morning of New Year’s Day 2009. The various cellphone angles of the shooting exploded onto YouTube and helped start nationwide protests almost immediately. The film itself is supposedly pretty true to actual events of that day as far as can be pieced together by Grant’s friends and family, and the cellphone images themselves. I ask the reader to leave any other examples in the comments section, but this movie should be seen as a groundbreaking piece of cinema for its attempt to bring clarity and humanity to a person defined by several minutes of confused mayhem. Fruitvale is far from being the first movie based on a true story, but I’m hard-pressed to think of a true story whose protagonist was so constrained by the events that made them famous. The Internet is a noisy place and will continue to be so as folks take full advantage of its revolutionary democracy of images and voices. It need not provide a haven to those voices alone. Socially activist cinema has a long and mostly proud tradition of providing a voice for those who have none, and now it’s in a curious place of being able to provide a voice for those who have simply been drowned out.

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

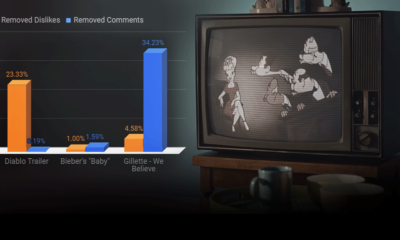

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films