Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

Exchange

For the Everyday Documentarian: From Idea to Impact

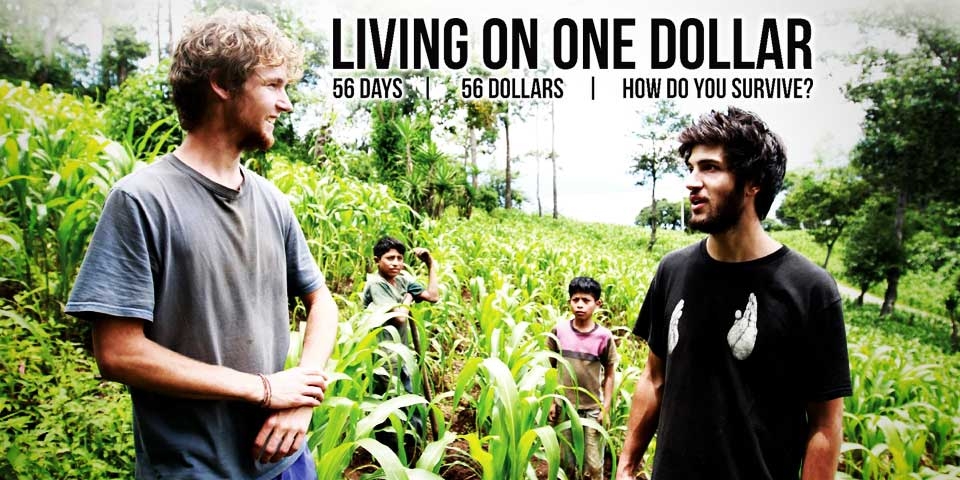

Chris Temple, one of the founders of Living on One, a documentary and impact campaign powerhouse, speaks to Cinema of Change about getting into the social impact entertainment space and what it takes to build a campaign around the film. Their documentaries, Living On One Dollar and Salam Neighbor, explore the pressing issues of poverty and the refugee crisis, and have gone on to create social and political change on an international level. Chris advocates for the everyday documentarian – anyone can and should make a documentary.

How does someone start in the impact entertainment space? What resources do you recommend?

Watch as much content as you possibly can. Follow other filmmakers across social media from diverse backgrounds. Check out No Film School. Start creating even when you don’t know how or doubt yourself! When it comes to making a documentary or any film for that matter, define your goals, audience, and intended change. Think about the primary impact dynamic, which is the #1 thing you want to come out of the film. Remember that filmmaking is a long journey. For Living On One Dollar, there were times when we were exporting version 65 of our cut and wondering how we would ever finish, but you’ll always make it happen in the end. And don’t let the gear hold you back! We filmed both our documentaries on DSLRs with lapel mics and H4N zooms. You don’t need a super fancy camera to tell a good story.

How can someone ensure that they don’t fall into “voluntourism” or have a “White Savior” attitude?

We never started our project with the goal of helping, but instead with a focus on learning. When we first embarked on our trip to Guatemala, we left with the intention of understanding the things we read about in our textbooks. And when we started to create the film, we partnered with organizations that were already doing incredible work on the ground. For example, through our collaboration with Mayan Families, we ensure that our donations go directly towards community development and are used effectively. Also recognize where you can add value, which for us was storytelling. Then, think about how you can support the cause and partner with people that can work in other aspects better than you can.

How do you cope with the emotions that arise during the documentary process?

At one point during our filming of Salam Neighbor, I didn’t want to be on camera anymore because it was an emotional moment. We were encouraging a young boy to go to school, yet later learned that his school had previously been bombed, so he experiences post-traumatic stress in school environments.

We have to recognize our own limitations as filmmakers and aid-makers, and express humility that we don’t have all the answers. The people we interacted with were the ones teaching us. They’re the experts in their own lives. We did experience some guilt coming home, almost reverse culture shock at our entitlement and culture of consumption, but guilt is not a productive emotion. It doesn’t create change; it just makes you feel worse, so how can you channel that feeling into action and creativity?

Recognize that the people you film with are people. Show the film to them before you release it online. Make updates. Continue building that relationship.

How do you overcome the fear of facing controversial subjects?

We were definitely nervous before entering the refugee camps, but realized that that stemmed from our implicit bias towards the Middle East and refugees from media and news. Of course, we sought advice from war journalists and had a 35-page security protocol, but never once did we feel unsafe.

How do you approach building a social impact campaign?

Any good impact campaign evolves from your story because the story is what people see and are moved by. Read impact guides like the one from AFI Docs Impact Lab or the Impact Field Guide. For Salam Neighbor, we focused on individualizing the refugee crisis and targeted communities that had huge refugee populations, yet weren’t really engaging with them, such as in Nebraska or Dallas Fort Worth, especially those places that were more conservative in their views of refugees. With 1001 Media, a fellow producer on the film based in the Middle East with cultural knowledge and historical perspectives, we launched an educational guide and are implementing that into the Common Core curriculum. We’re reaching out to teachers that we’ve worked with in the past and are hosting screenings as well.

How do you build partnerships with many of the development-based organizations and non-profits both in the United States and in the countries you work with? How do you approach such a collaboration?

The hardest part is starting out because you don’t have much credibility or a track record. You may only occasionally receive a reply, but listen as much as possible to those individuals who are willing to give advice. We actually connected with one of our mentors by just tweeting him again and again until he responded and agreed to watch our trailer. It’s a numbers game in some ways, but once you do hear back, prove that you’ve done your homework and are serious in what you’re asking. Have a specific question and show that you’ve gotten as far as you can without the extra help.

What has been the most difficult part of building the campaigns for Living On One Dollar and Salam Neighbor?

Finding the finances. Investors usually see a more direct reason to support a film versus an impact campaign. But slowly, we’re proving to funders that a national tour or building a curriculum is worth the time. Living On One Dollar was released years ago, but just last week, we ran a fundraiser to sponsor a new preschool in the community there. Our ongoing engagement with the community is very important to us. These stories and the impact we can make don’t end when the credits roll.

Out of curiosity, how has For My Son been doing? Do you see a difference in reach between VR and traditional film?

For My Son is most effective in person, which is why we brought it on tour and presented it at over 750 screenings as a VR exhibit. It’s currently an exhibit at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum! The technology for VR isn’t quite there yet to leapfrog into creating successful documentaries, but at the end of the day, it all depends on your goal.

What is coming up next?

We do have a feature documentary in the works that is inspired by individuals from previous films, kind of like a Boyhood, journey-of-their-lives style film. Stay tuned on our social media handles, @LivingonOne, as we will be providing teasers and more information soon!

Thank you, Chris, for speaking to Cinema of Change about your experiences with impact filmmaking. We hope audiences find this insightful and empowered to begin their own projects. As always, feel free to contact CoC or Living on One for advice, but remember to do your homework first!

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

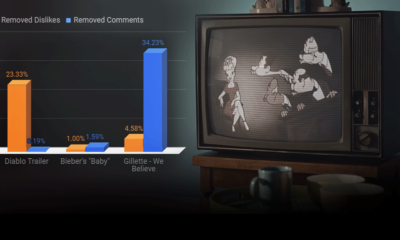

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films