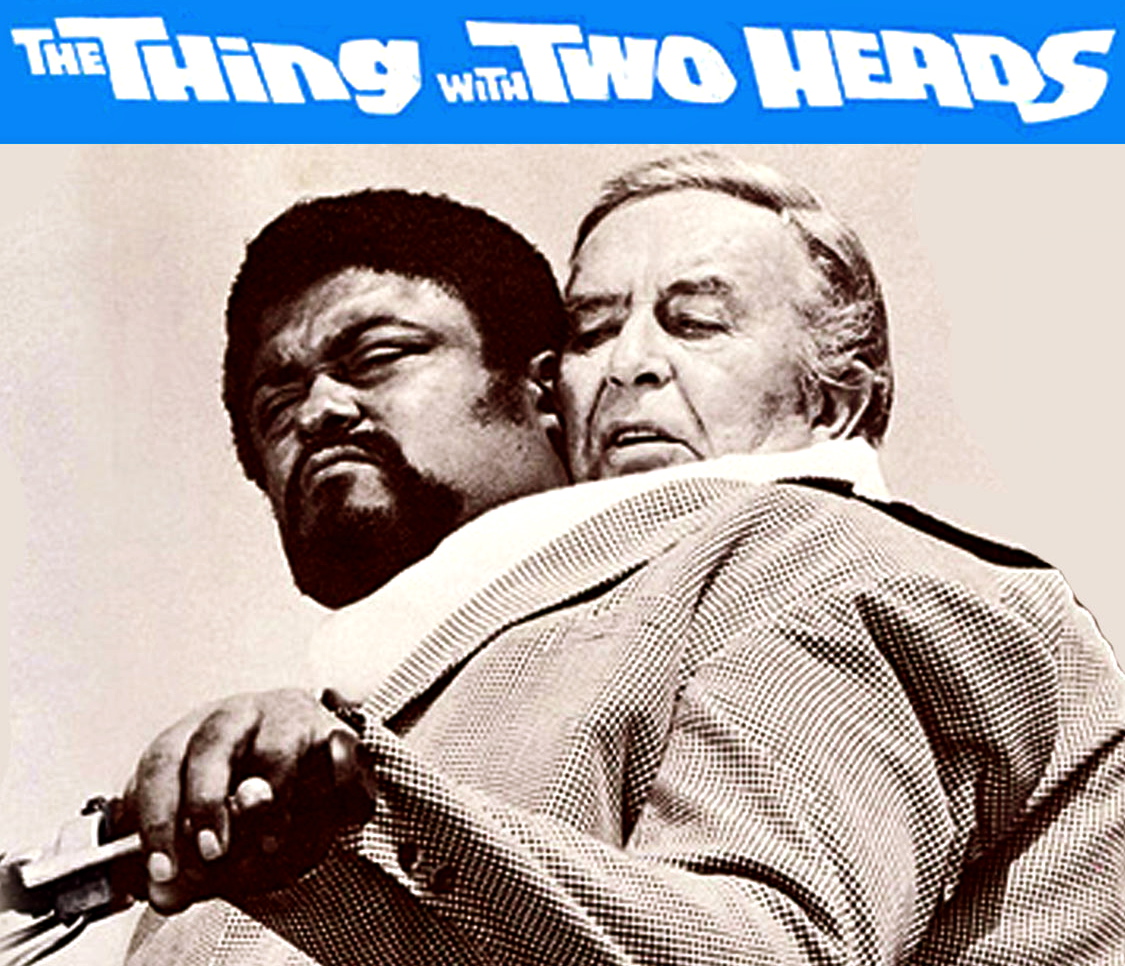

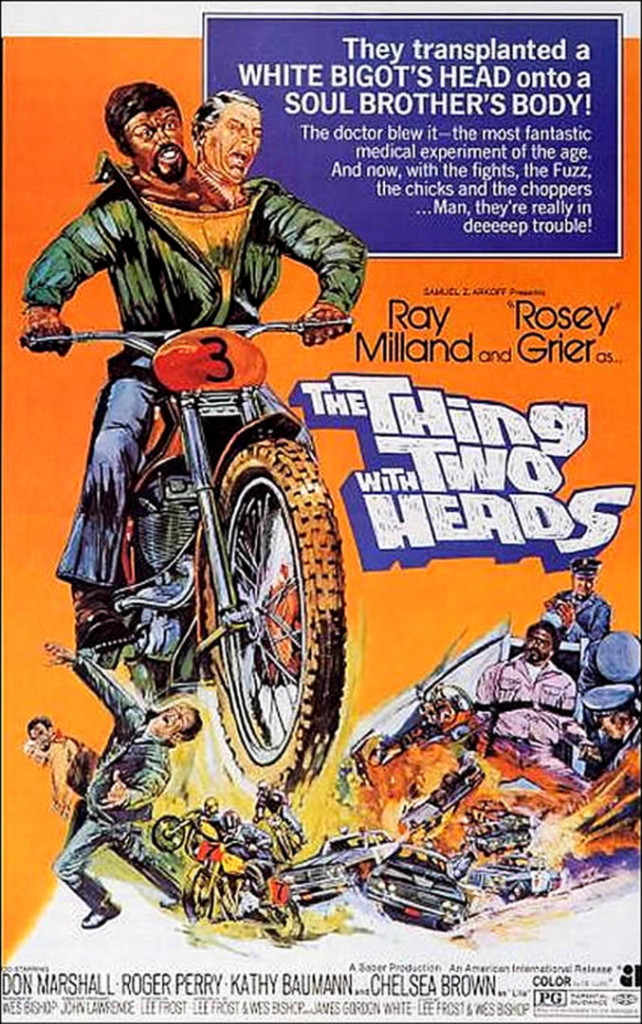

Wrongfully convicted of murder, this flick’s anti-hero (Roosevelt Greer) can’t seem to convince anyone of his innocence, so he takes a one of a kind opportunity to avoid the electric chair. The catch is he must share his body with a dying, but wealthy white racist (Ray Milland). You can almost hear the lighting strike and maniacal laughter from mere exposure to its tagline: They transplanted a white bigot’s head onto a soul brother’s body.

How could you not see this movie?

But once your ass gets in the seat, it’s easy to see how Two Heads falls flat and its conceit fails to bring any real

But once your ass gets in the seat, it’s easy to see how Two Heads falls flat and its conceit fails to bring any real

substance to the surface of interracial relations. Under director, Lee Frost’s lens, the collective “thing” bitches with itself and its repartee plays like the love-hate nucleus of a buddy cop movie without comic timing. Attached at the hip (not really, they’re likely stitched together at the neck), the unlikely duo set out outrun justice. Peppered with badass motorcycle chases and cop car explosions that aren’t exactly badass with a second serving of some not-so-special effects and jive turkey trash talk.

While Blaxploitation has always had a whiff of cheese to it, the genre’s onset provided black audiences opportunities to see black heroes on the silver screens and an alternative to the Uncle Tom films that mainstream Hollywood offered. The Thing with Two Heads bills itself as Blaxploitation, but seems to forget the substance of socio-political peril that fueled the exploitative aspects of the genre. Because the picture only remembers the shock factor, it enables the self-parody that contributed to the decline of blax films.

The blax genre busted into the cinematic scene in the late 60s, but became pretty synonymous with part of the freedom of the 70s cinema explosion that embraced a new, unfettered freedom, giving way to unforgettables such as Easy Rider (’69), Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (’70), and yes, Blaxploitation gems like Shaft (’71) and Super Fly (’72).

What is of particular interest and irony lies in the coined term itself: Black + Exploitation = Blaxploitation. This exploitation wasn’t just for the depictions on the screen, but also from the people in the streets. It appears that aside from the look, feel, and common tropes of the genre, the true defining factor of Blaxploitation is the studios’ exploitation of the urban African American market. The question of what and whom was being exploited is questioned in the conditions of the genre’s financers. In her 2007 article, “Movies and the Exploitation of Excess,” Mia Mask remarks that in order to meet the demands of African Americans, who at the time, made up 30 percent of the urban, first run theater audiences, studios cranked out dozens of cheaply made “black” films to turn a high and quick profit. Mask maintains that, “This cycle of films – most of which where produced by whites in Hollywood – desire for cinematic representation.”

What is of particular interest and irony lies in the coined term itself: Black + Exploitation = Blaxploitation. This exploitation wasn’t just for the depictions on the screen, but also from the people in the streets. It appears that aside from the look, feel, and common tropes of the genre, the true defining factor of Blaxploitation is the studios’ exploitation of the urban African American market. The question of what and whom was being exploited is questioned in the conditions of the genre’s financers. In her 2007 article, “Movies and the Exploitation of Excess,” Mia Mask remarks that in order to meet the demands of African Americans, who at the time, made up 30 percent of the urban, first run theater audiences, studios cranked out dozens of cheaply made “black” films to turn a high and quick profit. Mask maintains that, “This cycle of films – most of which where produced by whites in Hollywood – desire for cinematic representation.”

In 2015, The Thing with Two Heads serves as better as a historical artifact rather than actual entertainment. Except for its Z grade laugh ability, of course. But what does this historical artifact say? If African American audiences were salivating to be heard, for their stories to join the American film menagerie, did those audiences really crave The Thing and other nickel and dime movies?

Or were these desires thwarted by quick buck business, and did the cheaply made, underrepresented “black films” of the 70s contribute to a recycled misunderstanding of the African American struggle?

Consider the climate of 1972, when The Thing was released. America was just waking up from the 1960s and an explosion of culture change that spearheaded America into a major Civil Rights Movement. This is no joke. We’re not just talking about having dreams and holding signs, we’re talking about police brutality of an underclass, political assassinations of student leaders, CIA counterintelligence movements, the growing paranoia of Communism, Nixon’s abdication, the Seize of Chicago in ’67, the Vietnam War and its fecal flinging protests, not to mention the assassination of Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It’s a day and age filled with prison revolts and hippies and revolutionary suicide.

In short, the sins of America’s fathers were being paid by its youth, yet Black Cinema’s response is The Thing With Two Heads? How hip were the youth again? And what is cinema’s responsibility?

One of the greatest aspects of movies is, whether intended or not, these captured moving images and stories become locked into a time capsule that accompanies our history. Imagine the generation that sees The Thing or similar cheese and camp blax films. The impression it must leave is that race issues of the day were not to be taken seriously, which could be, perhaps, why some do not take race relations of the day with the level of reverence that could be present for said generation. All in all, Blaxploitation’s self parody provided a fatal blow for black film representation.

If you hang around the Facebook and Twitter water coolers, it becomes clear that the Black Community is not being heard. At least by mainstream America. Little Bobby Hutton becomes Michael Brown. West Oakland becomes Ferguson, MO. And the headlines turn to hashtags.

So, as these questions of inequality bubble to the surface of the American social conscience, Hollywood must ask itself what it has to say. What kind of stories will we tell? What heroes will grace our silver screens? Will movies lead the way and save America, or are we just a bunch of jive turkeys?

The Thing With Two Heads will offer you a lift, but beware, you’re in for a bumpy ride with no justice. Produced by Wes Bishop and John Lawrence. Distributed by American International. Canyadiggit?