SIE Magazine

Our Obsession with Story – A Survival Drive

We as filmmakers pursue a career in storytelling.

That seems trivial – of course, that is what filmmaking is about: storytelling. But if you just withdraw yourself for a moment and think from much further away, as an imaginary alien species that doesn’t tell stories, you realize that what we’re doing here on Earth seems absolutely bizarre:

The Strange Obsession With Story

There are people who imagine stories, write them down, and then there are actors playing out these stories, and finally there’s a crowd of people who watch these stories and pay money for it. People spend their hard-earned resources to keep those afloat that tell them stories.

I can understand that human buy clothes, that humans pay rent or buy food. All of those make sense. But when you think about humans buying the experience of stories being told to them, it just seems really odd. I challenge you as a reader to ask yourself this fundamental question: Why is it that you are watching films, that you are playing games, that you are reading fictional and non-fictional books? Ask beyond the “because I’m bored” answer.

For the past years, this question popped up over and over again: Why stories? What makes stories so special that we look forward to seeing a certain film or obsess over the allegedly life-changing experience of reading a book?

Over the past days, I had a breakthrough in my thought process. It happened on the bathroom mostly, which is where I incubate ideas – no matter if shower, toilet or bubble bath, this is my place of solitude and associative thinking culminating in some realization.

I was working on the Cinema of Change podcast with Joshua Oppenheimer that got me thinking about the connection between documentary and fictional narratives. I watched “Fail” and “Humans are Awesome” videos for breakfast. I went to my acting class and performed a scene as well as studying my fellow classmates’ acting work on stage, wondering why the hell we were doing this in the first place, and why I couldn’t take my eyes off their performances.

All of these played a role in my realization of why we have this incessant drive to consume stories: Stories are part of our survival drive.

Survival of the Educated

When we think back to “What were the first stories told?”, we zoom back into the stone age, when bipeds had climbed towards the top of the food chain and the Homo Sapiens family started developing higher intelligence than any other species on the planet. We walked upright, had four fingers and a thumb, and had these hands freely available for tasks that allowed us to rise to the occasion, such as building tools or painting caves.

When we’d come home from a long day of food collection, we probably told extremely primitive stories, through basic language or cave paintings – the earliest known cave painting dating 35,000 years back. “This is how we hunted down this sabretooth tiger”, or “This is how five of our tribe members died eating red berries in the forest”. If you didn’t listen to those stories, it might have been you who died the next day of the superior claws of a sabre-toothed cat or from eating poison berries.

Listening to these stories of your tribe members was a simple means of informing yourself on how to stay alive.

Later in human history, you’d read and watch theatre plays that told great tales of human connection, deception, love, intrigue and so on – and allowed you to learn about how to interact with other people, how to relate to the society around you. At that point, it was less the sabre-toothed cats or poison berries that were dangerous to you – it was botched social relationships and failed romantic engagements that posed a major threat to you participating in the gene pool and pass on your DNA to the next generation.

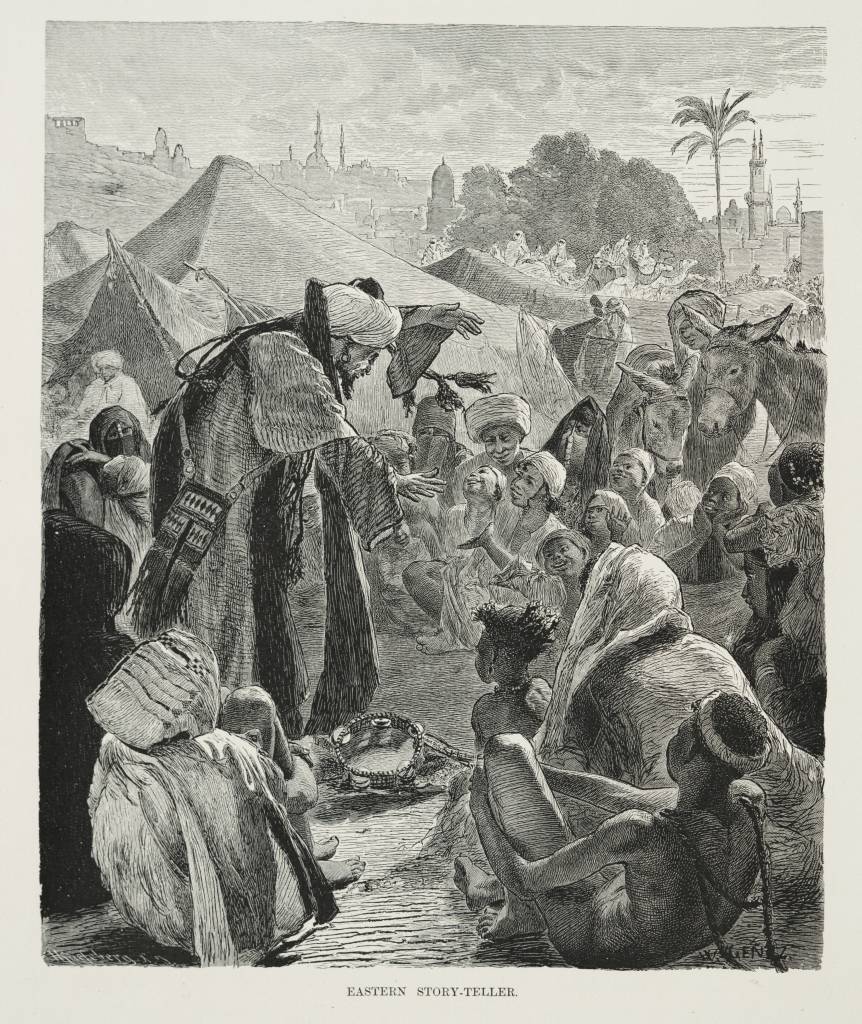

An Eastern Storyteller from the 19th century – storytelling and artworks depicting this process were spread around the entire world, as if it was an universal form of human communication.

And nowadays, we watch and read all sorts of stories – no matter if Zombie Apocalypse, Romantic Comedy, gritty Western, or a touching Drama – all of them have one not necessarily intended commonality: They teach us about the world, about people, and about ourselves. Not only is the consumption of stories survival-driven, but the telling of them is as well.

Why are we so keen to tell our friends what happened to us last weekend? Why do people invest decades of their life living an abysmal existence as indie filmmakers or as struggling novelists, despite having all the education needed to easily prosper in another field and live comfortably?

My suggestion is that deep down, we want our “tribe” to survive; our closest group of friends should learn from our successes and misfortunes. So, we pass on our experiences, and we achieve that by telling a personal story. The screenplay writer is doing just that as well, but to a far larger potential audience. Over the millenia, we evolved our stories from simple “how I killed the sabre-tooth cat” explanative narratives to complicated, artistic, indirect, poetic pieces of story that take a lot longer to decode their exact learning lessons out of the literary shell.

If I look at myself, there’s a good reason why I was so obsessed with certain content:

I loved watching “The OC” because it taught me so much about romance, love, boyfriend<>girlfriend dynamics and social relationships. I still love watching Fail videos – car accidents, stupid sporting incidents, general Schadenfreude-inducing misfortune – because I can learn about how to avoid getting hurt or killed by sheer stupidity.

I love reading books that teach me about survival in the film industry, which in turn allows me to produce a safer livelihood for myself and pick better chances to transcend the Starving Artist syndrome. For nearly any piece of entertainment I consume, I can find some relevance to my own survival and well-being through this consumption of information.

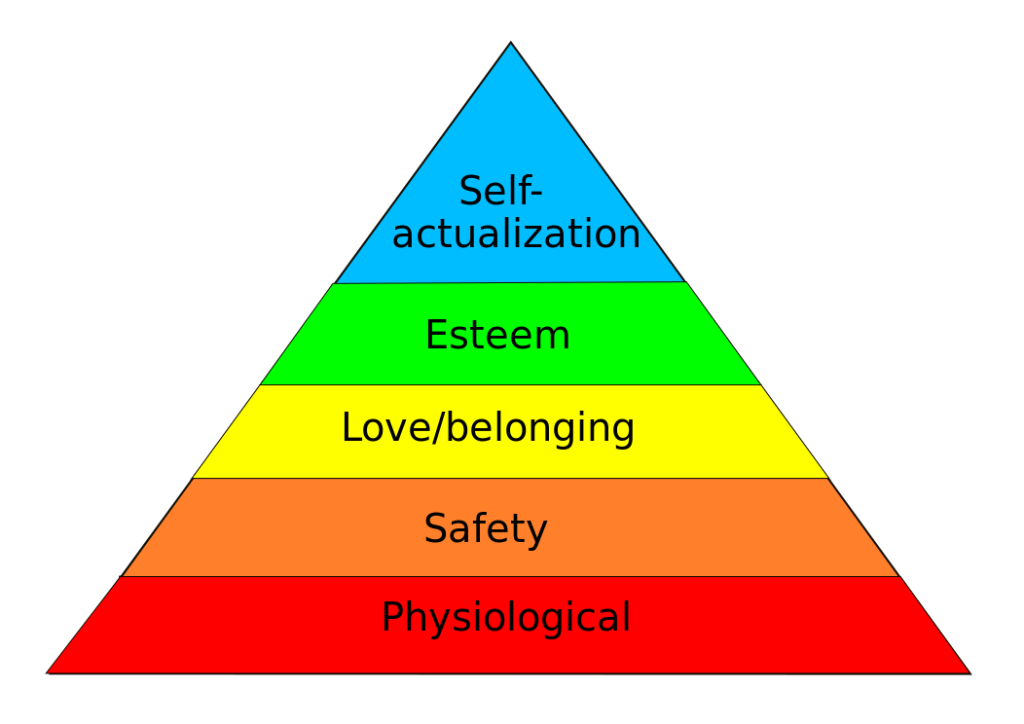

When we look at watching films, we could classify scenes into learning lessons within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: The love scene helps us with learning about love and belonging; the fight scene helps us to expand our need for safety; the “Cast Away” plot helps us learn about our physiological need for sleep, hunger and shelter.

Hungry for Relevant Information

In a way, our endless consumption of information is, in one way or the other, an instinct to help us survive. We don’t just open the phone book and try to memorize all the names in there, since this consumption of organized information yields little to no survival benefit. But we love watching viral videos, as they teach us about the Zeitgeist. We love watching TV shows, as they allow us to relate to our colleagues and friends in terms of shared interests. Nearly all this organized, comprehensive information allows us to further our social status and become a functional member of society, on a small and personal as well as a big and professional scale.

And it just happens to be that one of our favorite ways of consuming this information is through stories. An incredible, under-appreciated book on this subject of “What makes stories themselves so powerful” is “Story Proof” by Kendall Haven. For my thesis “Cinema of Change: The Persuasive Impact of Narrative Motion Pictures on Individual and Society”, this book was instrumental in forming a theory on how story works on a neuroscientific level. One of the main points in the book is that we’re exposed to stories from an early point in our lives , through fables and fairytales and bedtime stories. Another theory is about information organization in the human brain, and theorizes that we organize information in the story format.

Whether it is nature or nurture, we have a unique disposition towards information that is organized around characters, plot and struggle. If we notice any of these elements in a piece of text, imagery or motion picture, we become extra-perceptive and are able to memorize information with greater ease. Which is funny, because 90% of our education system rests on a completely contrary style of information delivery, which is arguably incredibly inefficient.

In a good film, there are multiple stories running simultaneously, and we can’t get enough: The music is telling a story, the visual is telling another. There is the story of each character, the story that the plot itself provides, the story that is being said, and the story of what is being left unsaid.

The 4D Stories being told by a screen – it’s simply a change of medium, but the fascination and desire for this experience stays the same.

An Undying Obsession

It is really quite miraculous if you think about the intricate system of motion picture entertainment that we have developed to simply consume survival-relevant information.

Critics will argue that this I subscribe to the theory of Evolutionary Psychology with my article, and that is completely correct. The critique is perfectly appropriate insofar that my thought model here has similar testability problems as Evolutionary Psychology itself has, which is one of its major lacks as a scientific theory.

Naturally, this is not the only dimension of story and its fascination for us humans. Knowing this, I do however willingly go on a reductionistic leg and suggest that the information-consumptive survival drive is the primary force behind our undying fascination for story.

As long as we’re not able to learn about the world in more effective ways than through stories – which are arguably the most information-dense form of education at our disposal – we will not stop telling them.

And in an ever-more complex world, we will stay hungry for more stories.

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Media Impact

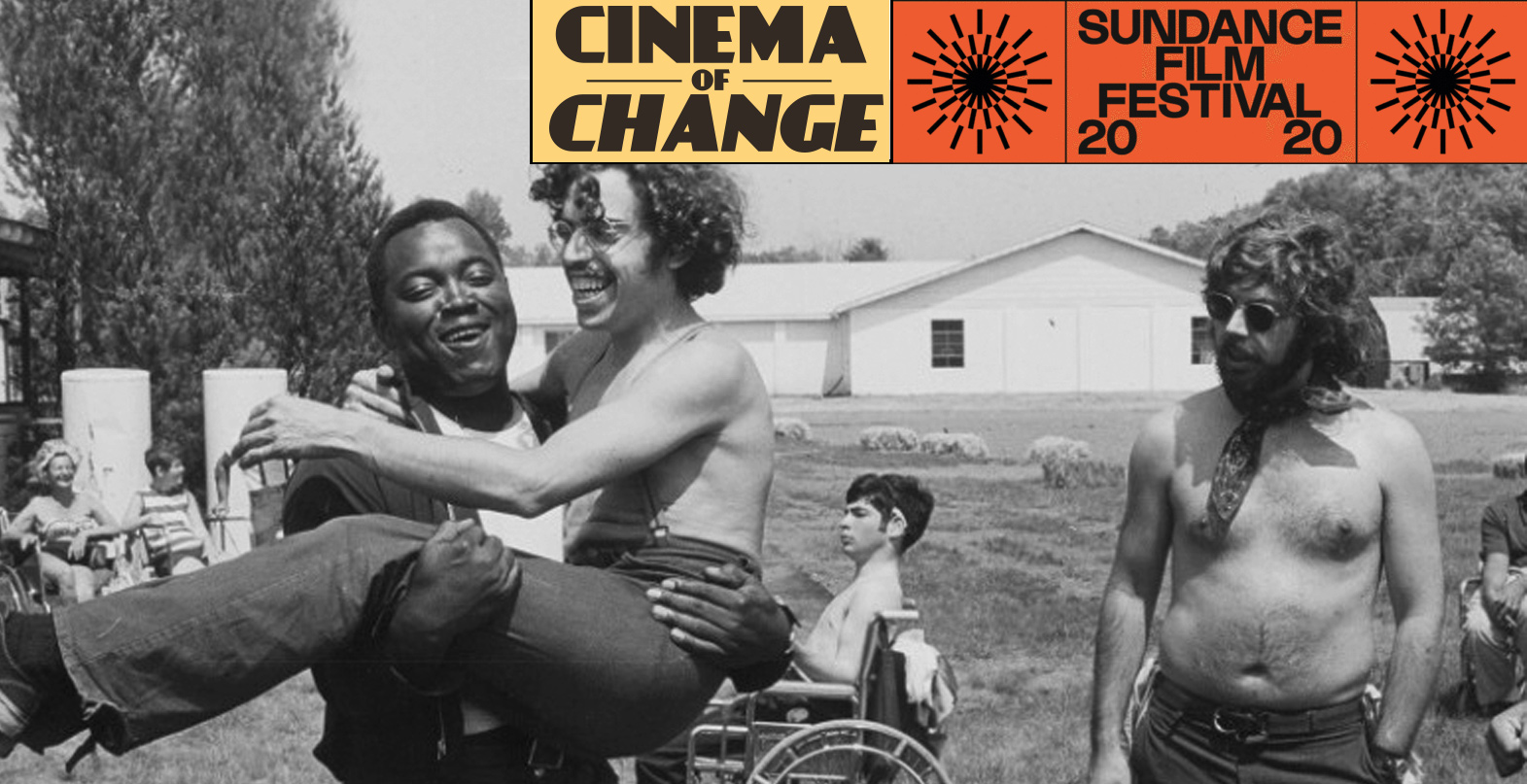

“Crip Camp”: Unified Disability opens Sundance 2020

What happens when a bunch of teenagers go to summer camp in their height of puberty? The wreak havoc, have a great time, try some contraband drugs, and fool around with each other in a virginity-defying quest for adulthood. What happens if these teenagers have Polio, Cerebral Palsy, Down Syndrome, Spina Bifida or MS? The same thing. Just with a lot more wheelchairs involved in the baseball games and make-out sessions.

That’s the world “Crip Camp” introduces us to – for the first 40 minutes of the film, we are immersed in a wonderfully “inappropriate” summer camp Jened in upstate New York. This camp, founded by parents of kids with Cerebral Palsy, operated for nearly 20 years (approx. 1960-1980 with a second 25-year-run in another location until the early 2000s, which isn’t mentioned in the film) and provided an un-sheltered source of freedom for disabled teenagers, and an opportunity for human connection and growth to camp counselors from all over the United States.

Pity VS Profanity

Many films about disability utilize pathos, pity and pain. They are careful in the treatment of their characters and not to step on any toes – a bit like the THR review of the film. And while there is a lot of that in a disabled person’s life – and in many people’s lives regardless of ability – there’s plenty of joy, profanity and profound insights to be had in a film about disability. And, unlike the THR tip-toeing, it’s massively liberating how the film dealt with disability. Not as weakness or fragility, but as a simple fact of life. These are awesome people sharing hilarious and moving insights in what it’s like to be in their shoes.

I might be stepping on toes here, but in my experience with friends and acqinantes with disabilities, none of them want to be linguistically or physically babied or touched with white gloves. There are obvious physical needs that different disabilities come with, but I don’t think it’s productive to be all too sensitive around a person with a disability – it creates the same sort of “separate but equal” impression that sending them off to their own school does. And I think this true equality, making fun of each other and treating each other like we’re on the same level, leads to much more honest relationships.

One of my personal favorites of this level-headed approaches in the film was one of the camp alums recounting a story of his first date in the camp, along the lines: “A camp counselor taught me how to kiss the night before. That was the best physical therapy I’ve ever received. And then the next day, I had my first date with this girl at the camp. She touched my … cock. It was wonderful.” I’ve had similar conversations with quadruplegic friends in my personal life. Many disabled teenagers are perverts just like the rest of us.

These are simply not the things you’d expect if you’re an outsider – but they are the common thread that break assumptions and prejudice. When someone curses on screen, you know you can practically trust them, and there’s no need to put on a pity party. The use of humor is brilliantly applied in Crip Camp to remove barriers – whether it’s barriers between disabled groups, or barriers between the disabled world and the other 80-ish% of the population.

You might say, oh please, we all have disabled people in our lives, and things are much better now. Sure, most of us know a number of people with disabilities. They make up about 20% of the world’s population, practically forming the largest minority on the globe – and it’s hard to avoid getting to know 1 in 5 people. That doesn’t change anything about the fact that there’s still no true equity, and while a lot has happened since the Camp Jened era of the 1960s, 2020 is still full of employment discrimination and false assumptions. As long as you’re not personally affected by birth, disability is easy to ignore. Well, chances are that 1 in 4 of 20-year-olds will become disabled before retirement.

A line in the film profoundly illustrates this invisible divide. Jim LeBrecht, one of the two directors of the film (along Nicole Newnham) and himself having been born with Spina Bifida, recalls his father giving him advice when he was admitted to a public school: “You’ll have to introduce yourself to other kids. You have to approach them and say hello, because they will be afraid to talk to you.”

As filmmakers from all walks of life, the portrayal of people with disabilities on screen is a challenge – not so much in this film because it’s a film made by the community for the community. For those that don’t quite have good access or understanding of disability, RespectAbility’s “Hollywood Disability Toolkit” is a truly comprehensive 50-page guide to do things better. Unfortunately, the guide doesn’t directly recommend to make your disabled characters swear and talk about teenage sexuality – but that doesn’t change anything about the fact that these are powerful tools to disarm your audiences’ potential “fear of the other”. In the end, we’re all just people that can relate to each other’s human experience.

Record Occupations and Missing Footnotes

The film allows us to follow the teenage troublemakers of Camp Janed into their adult lives, where a number of them become political activists, deeply involved in pushing disability rights issues. Crip Camp focuses on one of the campers with Polio, Judy Heumann, who leads a street blockade in 1970s New York for disability rights and then graduates to West Coast activism, gaining continuous steam for the cause, up to the epic mid-point of the film, where hundreds of people with disabilities stage the “504 Sit-In” in the Health, Education and Welfare offices of the Federal Building in San Francisco. Joseph Califano, administrator of the HEW at the time, was unwilling to sign Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was supposed to ban publicly funded discrimination against people with disabilities. Judy and a number of other well-organized community leaders took over the building and made history: The sit-in was the longest occupation of a federal building in the existence of the U.S. (which the film doesn’t quite mention in its historical gravitas). Even Drunk History made an episode on this badass move.

The “Capitol Crawl”, where wheelchair users of all kinds shed their wheelchairs and climbed the non-accessible stairs to the highest symbol of U.S. politics, the capitol.

Up to this point, we’re wrapped up in a beautiful storyline of these teenagers-turned-activists, and appropriately traces the tremendous power the 504 sit-in and Judy Heumann’s delegation trip to Washington had with convincing Califano (after holding candlelight vigils in front of his house and following him to public appearances) to sign 504 into power.

The film then takes a bit of a leap of faith in simplifying the history of the American Disabilities Act of 1990, which followed nearly 17 years later. For the uninitiated, this is the act that put wheelchair ramps into place in all public buildings and gave a lot of protection to people with disabilities, opening up countless new avenues of opportunity – “to assure equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities.” I wondered many times what stars had to align for the disabled communities to have so much unified political power (as they had 30 years ago) to push through such an incredible piece of legislation. On an international level for example, countries like Austria and Japan have had quite pitiful disability laws in comparison to the U.S., usually lagging behind 15-25 years. The ADA was the first act in the world to give such wide support to people with disabilities, and positioned the Bush Senior-era U.S. as the global leader in disability relations.

The film’s narrative centers around direct action and activism like the Capitol Crawl. While these are cinematic moments and films need to simplify history to fit a narrative in a limited amount of time, it gives us a wrong impression of how history happens.

Work like the professional lobbying of Patrisha Wright, or the institutional recommendations of government agencies like the National Council on Disability were instrumental in shifting the tide in favor of the ADA, and the film unfortunately makes no mention of it. I’m not suggesting that the film is under an oscar-speech-style obligation of rattling down all people that should be thanked for the ADA, or that it needs to dive into the complicated politics at the top that made this happen. It would have simply been a nice gesture to have one of the interviewees give a footnote a la “a lot of other things had to work out, outside of our lead character’s activism, to get a historical bill like this put on the table and signed into existence.” As this film can serve as a role model for future activists, it carries some reasonable responsibility to not accidentally further a naive, romantic narrative of “magical activism and easy social change”.

Social change is incredibly difficult, and the people that achieve it study large scale systems, build powerful alliances and invest decades of their lives to utilize the right time in history in order to make a dent in the universe.

United towards Accessibility

This film is about people from all walks of disability and ability coming together to crush an unfair system and fight for accessibility. Together. United. The way it should be. The stories of Crip Camp and the ADA are rather rare exceptions to the usually fractured communities of people with disabilities. As you can imagine, each community has their own interests and doesn’t always see an incentive to support another community. Yet, politically speaking, individual disabilities usually make up single-digit percentages on a global level, but all disabled communities united form a 15-20% front, the “largest minority in the world”, according to the WHO. The more united this front, the more likely things like the ADA can happen again and re-balance the world.

Watch Crip Camp and get inspired. Join or support an organization like RespectAbility that actively works on re-unifying the disability community for political leverage. As humans, we are better than just shunning our fellow humans because of some genetic variation, accident or other circumstance. There’s so much to be gained from creating an equally accessible world for all – and right now, that’s not the case.

Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

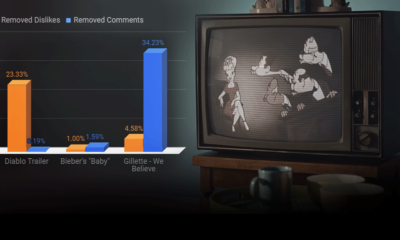

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films