Filmmakers

Learning Ethnic Relations On and Off Screen

I have been fascinated and engrossed in films for as long as I can remember. Even as a child I knew I wanted to make movies. At six years old I remember seeing my first film in a theater. It was DR. DOLITTLE. Shortly after that I saw the Godzilla movie, DESTROY ALL MONSTERS and PLANET OF THE APES. I was hooked and I wanted to make movies with monsters, disasters and fantasy. By the time I was about eight or nine, I was regularly watching Creature Feature late on Saturday nights and the 4PM matinee every day after school. These were on Channel 10 out of Rochester. We only had three channels, 8, 10 and 13. No Youtube, no cable, no streaming, no DVD and even VHS was yet to arrive on the scene. My film exposure was limited to what I saw on broadcast TV and the two movie theaters were about 25 miles from my small town. Many days on the 4PM matinee they’d play old movies that did not interest me and I’d change the channel to cartoons. If I didn’t see a monster in the first few minutes, it was carton time. Movies were my entertainment. That’s how I consumed them. That’s what they were to me. If I wasn’t entertained, I changed channels. I had yet to understand the transformational power of film, let alone the craft and art of filmmaking. All that changed with the convergence of two events in my young life. One was film related, the other was life related.

A Film That Shaped Me Early in Life

That watershed, filmic experience came on the 4pm movie matinee. As I plopped down in front of the television hoping for a monster movie or at least some action and adventure, black and white credits with soft music began to roll. It wasn’t looking good. Then I saw a cigar box of wonderful treasure… crayons, a harmonica, a pocket watch, an Indian Head Penny. Children’s treasures. This was not the kind of movie that generally interested me, but I was immediately drawn into it. Especially when the young characters Scout, Jem and Dill appeared. They were kids like me. This of course was TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD. And I remember full well that first time I saw it and the spell it cast on me as a child. It impacted me in ways I could not yet understand as a nine year old. Atticus Finch was larger than life to me. He was soft-spoken, thoughtful and on the side of right. The life lessons he imparted on Scout, he imparted on me. He was talking to me. I wanted to climb into the television set and move in with Finch Family! I wanted Jem and Scout as my brother and sister and Atticus as my father. Don’t get the wrong impression, I had a wonderful childhood in my small town, but I wanted to be part of that world, where Atticus explained things in ways I could understand. This was also the first time I can recall hearing the word “nigger”. When Scout utters it and Atticus reacts as he does, I knew it was not a good thing. And as the film played out I was given my first and the most formative lesson on race that I’ve ever had. And it came from Atticus Finch and TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD.

When Life and Fiction Intersect

A short time after seeing To Kill A Mocking Bird, the life event occurred; it was the first time I ever met a black person my own age. It happened on the sidewalk in front of Mack’s Branch Store. This was a place where we kids hung out, read comic books, bought candy and generally lingered when we didn’t want to go home. It was nearing the end of the summer and my friends and I were out front of Mack’s drawing on the sidewalk with colored chalk. I was drawing monsters of course. As I stood up to admire my work, two black kids, walked quickly past us and into the store. A boy and a girl. My friends and I looked at each other, questioningly. Finally someone said, “Who are they?” I wasn’t sure. “Where did they come from?” I certainly didn’t know.

You have to understand that there were no black people in my small, Upstate New York farm town. I had little exposure to black people save for the occasional student at the local college. And black kids? Never. And I’d never been exposed to prejudice or seen it play out in my town. For the most part I’d been insulated from the tumultuous sixties by this quiet little village. The Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam, the assassinations. These things were barely on my radar. My parents limited what news I watched, but movies were unlimited. So the only thing that went through my mind when I saw these kids was Atticus Finch and To Kill A Mockingbird.

As my friends and I traded theories as to who these kids were, they came back out with their candy and sodas. We all looked at each other. The little girl held her older brother’s hand tight and whispered something in his ear. All of us went back to drawing as the boy stepped closer and watched us. He was probably about my age, his sister, who hid behind him was a few years younger.

I kept drawing. Kept to myself. Didn’t engage. Not because I had anything against these kids, but because they were unknown and foreign to my friends and me. They just weren’t like me. I kept drawing my Godzilla. They kept watching. I wished they would just leave. But then I thought about Atticus and what he might have counseled me to do. I knew I shouldn’t be ignoring them, but what should I do? I didn’t know. I thought about it as I colored in Godzilla’s eyes. They probably don’t know what to say either. Atticus would want me to say something… but what? So I did what I always do. I talked about movies. “Do you like monster movies?” And so it went. We talked about monsters. I told them about the one that lived in our lake. They didn’t believe me. We talked about our favorite monster movies. Before long we were talking about everything and they were coloring the sidewalk with us. We learned that they were the children of migrant workers who’d come to the area to help pick apples and do seasonal farm work.

I saw the chalk dust on their black legs and hands and thought how different they were from me. I heard them both laugh as the little girl tried to color her brother’s face and I thought how much they were the same as me. And I saw them smile and play… here… with us and I was thankful for the lessons Atticus Finch had taught me.

Long-Term Perspective as a Filmmaker and as a Person

Years later I saw the film again, projected in 16mm in my 9th grade English class and I read Harper Lee’s novel. I was moved all over again.

It was one of the films that pushed me to Hollywood to become a filmmaker. I even snuck into director Robert Mulligan’s office on the Fox lot and got his autograph when I was a college freshman. And While attending film school at USC I took a job as a tour guide at Universal Studios where To Kill A Mockingbird had been filmed. As I began my tour guide training, I would wander the back lot to memorize all the sets. Near the end of one long day, I walked around the curve of one small lane and saw the Finch’s house for the first time. Drawn to it, I stepped up on the porch and sat in the porch swing where Atticus had sat with Scout. I sat there so long, I missed the van back to the upper lot, but it didn’t matter. In the fading light I sat there thinking about the film and I understood finally what that film meant to me and what it had done for me.

I wondered what might have happened had the order of those two childhood events been reversed. What if I had met those kids before I’d seen To Kill A Mockingbird. Likely I would not have spoken to them. I would have kept to myself, safe from engaging with the unknown. And that formative moment in my life would have played out very differently.

I am the filmmaker I am today because of the power of film. But I can honestly say that I am also the person I am today because of the power of film. That’s where the true power of film lies. Not only to entertain, but to influence hearts and minds and perhaps… just perhaps, inspire us to be better people.

Thank you, Atticus.

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

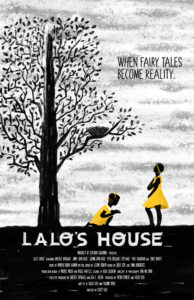

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

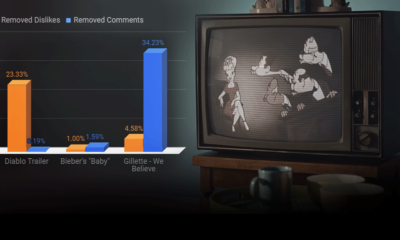

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films