Companies

Hollywood: To Pivot or Perish?

What happened to the days of classical Hollywood when hit movies weren’t a sequel or some variation thereof? When a film wasn’t made on the bias to hit upwards of a billion dollars through immense amounts of action to keep us stimulated? Today, I think many would agree these aspects of the entertainment industry are what continue to be detrimental to the heart and soul that used to be Hollywood. When referring to “Hollywood,” I am speaking of archetypal studios like Paramount, Warner Brothers, etc., which have all been pillars in the formation of the industry; a time when original screenplays would get green-lit more often than screenplay adaptions. When referring to the “entertainment industry,” I am speaking of all companies young and old that contribute to the pool of film and media content. However, today we see studios that were once powerhouses now struggling to stay afloat; MGM is perhaps a key example of this type of decline. Now our movie-going experience has completely transformed, and who is to blame? Moviegoers and filmmakers seem to all have different theories; some blame media-tech companies like Netflix that keep people comfortable in their homes, others blame globalization as China continues to have a larger influence over the films America produces, and others simply blame consumers, claiming audiences today are harder to please. Perhaps all of the above are true, but what few have bothered to examine are the effects conventional economics has had on Hollywood. What this article will try to prove is how Hollywood continues to dig its own grave by focusing narrowly on the same conventional economic model, thus failing to adapt to behavioral economics. I will take from sources on the web that discuss relevant topics in the entertainment industry, while supplementing with works from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow, Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational, as well as other key points from Ry Schill, a professor at Cambridge who I had the pleasure of working with this summer. Ultimately, Hollywood’s direction should cause us to ask ourselves where it will be in 10, 20 or 30 plus years. As a cultural industry, how can it thrive if it is becoming so narrowly focused on “tentpole” films that strip originality away not just from those involved in making the films, but also those who watch? Who will, or who has already started to fill this void Hollywood is creating in producing unoriginal and regurgitated stories? Answers to such questions will paint a larger narrative as to where Hollywood could potentially end up in the future, and how behavioral economics could pivot the trajectory of an industry that is thriving on short-term successes.

YOUR BRAIN & ITS BIASES (TRUST ME, YOU DON’T WANT TO SKIM THIS PART)

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman discusses the differences between the System 1 and System 2 parts of the brain. He describes System 1 as operating “automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control,” while System 2 “allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations.”[1] For the sake of argument, lets consider the entertainment industry having a mind of its own that, much like a human’s mind, battles between its System 1 and 2 preferences. However, entertainment’s System 1 has a streamlined goal that operates on a linear equation with little room for flexibility. In the mind of Hollywood today, its System 1 goal is to produce content that reaps (huge) profit, gains in popularity, and if at all possible ensures the making of a sequel for a sense of short-term security. As Kehneman would suggest, these kinds of acts of security operate within System 1 to create an illusion, where one’s understanding of the past “feeds the further illusion that one can predict and control the future. These illusions are comforting. They reduce the anxiety that we would experience if allowed ourselves to fully acknowledge the uncertainties.”[2] However, System 2 recognizes the risks in operating linearly, bearing in mind the social aspects involved in creating such one-sided content for consumers. It recognizes the need to fulfill originality as a cultural industry, fearing the linear equation that could effect the long-term through short-term successes. By putting each system in conversation with one another, behavioral economics can help create a balance in seeing how each operate together to reach the same end goal.

YOUR BRAIN + HOLLYWOOD’S “BRAIN”

Many aspects of Hollywood today continue to inhibit itself from recognizing the behavioral elements of its own industry by focusing narrowly on its economic gains. Hollywood now aims (and thrives) on tentpole films, big budget movies that will have promising global returns. Examples of tentpole films include the Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games, Fast & Furious, etc. Making these films that guarantee at least 3 sequels is where Hollywood continues to peg itself in becoming an industry that makes only large grandiose films. This has become an issue of relativity, as Ariely suggests, “we not only tend to compare things with one another but also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable – and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily.”[3] It is allowing for its System 1 to pervade System 2 in agreeing for the remake of certain films based, perhaps unintentionally, on the comparison of films like Titanic and Avatar that created a historically high standard as to what it meant to succeed (let’s not forget, these two films were black swans, many feared their potential and saw them as financial suicide). These actions are contributing also to what Kahneman would call a “hindsight bias” where in this case it leads studio execs “to assess the quality of a decision not by whether the process was sound but by whether its outcome was good or bad.”[4] Thus, because the Fast & Furious franchise has done so well at the box office, Hollywood sees danger in grappling with its System 2 to create something fresh. Instead, responding to its System 1 method seems like the safest bet in making (now seven) Fast & Furious films for the sake of profit. Let me be clear, I work in entertainment and have a fond admiration for what our executives do (as I aspire to perhaps fill their shoes one day), however what Hollywood is missing now is a sense of equilibrium; and when and if I do fill the shoes of an executive I want there to be a sense of balance in the content we consume. Right now, Hollywood’s current method is detrimental to it as an industry, and arguably to society’s culture as a whole. With this System 1 model, Hollywood will undoubtedly continue to make Fast & Furious films until the day they stop generating profit, at which point the industry will frantically move on to the next tentpole at the expense of original films with original screenplays (and who knows, there could be the next Avatar buried in all the unread stacks of screenplays collecting dust on an intern’s desk). It has started to create a dichotomy in society’s cultural entertainment: tentpole films vs. all other films. It’s no surprise that today “all other films” are struggling to remain relevant in Hollywood, as its outrageous anchoring effect continues to affect subsequent judgments of box office success. This anchoring effect has introduced an entirely new standard as to what it means to create a successful film with Avatar grossing $2.7 billion worldwide, causing us to question how much longer other films of a less grandiose nature have left to survive in mainstream Hollywood.

With this narrow trajectory of tentpole filmmaking for the sake of massive gains, it gives rise to the question as to where Hollywood is destined to go as it continues see all other films as financial suicide. Many have tried to answer this, and some of Hollywood’s greatest minds have said Hollywood is on the brink of a major implosion. Steven Spielberg has been quoted in believing that it will take a few half dozen blockbusters to flop at the box office to alter the industry forever.[5] He then predicts that price variances at movie theaters could be introduced where, “you’re gonna (sic) have to pay $25 for the next Iron Man, you’re probably only going to have to pay $7 to see Lincoln.”[6] Spielberg then went on to say that Lincoln “came ‘this close’ to being an HBO movie instead of a theatrical release.”[7] Similarly, George Lucas suggests movies could turn “into a Broadway play model, whereby fewer movies are released, they stay in theaters for a year and ticket prices are much higher.”[8] If a movie like Lincoln was close to becoming an HBO film, this has heavy implications on Hollywood’s potential trajectory. If Hollywood wishes to continue as a large player in producing content with a balanced portfolio, it must pivot. By contributing behavioral economics to its overdone, conventional economic tendencies it could save itself from sewing the seeds to its own destruction.

YOUR BRAIN + HOLLYWOOD’S “BRAIN” + REAL-LIFE EXAMPLE

One prevalent instance to Hollywood’s self-destruction is the writer’s strike of 2007-2008 that lasted nearly 100 days. As The Los Angeles Times noted, the walkout cost an estimated $3 billion to the local economy, shedding light on how heavily reliant the city of Los Angeles is on the contribution of employees in entertainment.[9] The writer’s walked out of their jobs largely to mandate payments on shows displayed via the web while also securing the WGA’s authority for programming on the Internet. Up until that point, studios mocked at writer’s who were demanding such seemingly reasonable requests, suggesting they instead receive “multiyear study”, a tradeoff that still had Hollywood reaping most of the profit and leaving its writers exploited and overworked.[10] This strike is one dramatic example as to how Hollywood’s attentional bias is condoning irrational behavior on an internal, corporate level. Hollywood continues to operate by focusing on one or two solutions to a problem, while ignoring the rest. Its attentional bias leaves it focusing narrowly on issues that should receive more notice, much like the strike that started small but quickly grew, or the creation of tentpoles. Ultimately the writers won a hard battle, but still fell short under Hollywood’s new contract. In the end, “writers received guarantees that any guild member hired to create original shows for the Web would be covered under a union contract. But the tentative contract enables studios to hire nonunion writers to work on low-budget Internet shows, giving them flexibility they sought to compete…”[11] The strike disrupted not just the studios involved, but also the local economy and much of the nation’s audiences who expected new shows on television.

The writer’s strike was one of the most detrimental strikes in Hollywood in recent years. If Hollywood wishes to remain competitive as a cultural industry at least in the market of original content it must refocus, which is where behavioral economics could play a key part in this solution. Behavioral economics will help add to its current models in seeing beyond the linear equation of how to maximize profit. Behavioral economics recognizes biases (such as the ones previously mentioned) and uses them as vehicles to prevent detrimental events like the writer’s strike. Unfortunately it seems to take Hollywood such extremes in order for it to recognize the need for certain benefits and changes in policy to keep its industry moving forward. Hollywood shouldn’t wait until the next strike or until a dozen blockbusters flop to bring change, which is where a model that introduces a mix of economics and psychology could create equality within its corporate sectors and a sense of equilibrium in theaters. Furthermore, Hollywood’s perceived glamour continues to attract talented employees but fails at appreciating lower levels of management through indecent pay and difficult working conditions. It has successfully created a gambler’s fallacy as an industry, causing its lower-tiered employees to be exploited in also operating on the hope of achieving great success and respect. This has allowed for an intense stratification of wealth between employees and a legitimization of poor working conditions. However, this old-fashioned hierarchical pyramid is quickly being challenged as newer companies like Hulu are forming, changing the way the entertainment industry operates.

OLD HOLLYWOOD VERSUS NEW HOLLYWOOD

Hollywood is not changing, and as a result it is allowing younger companies to learn from its stagnation in fixing the way the entire entertainment industry runs. Netflix was (arguably) a pillar in this change, introducing not just progressive original content but also progressive working conditions and very high salaries. There’s no rational reason as to why Hollywood couldn’t at least strive for these goals before VOD (video on demand) and younger companies alike, other than the fact that it is stuck in operating within System 1. Hollywood operates until it is on the brink of a disaster before it justifies its need to change, and as result it has turned into an industry that produces selective films while suppressing upward mobility. If Hollywood embraced behavioral economics just as other VOD/entertainment-tech companies have started to do, it would see greater returns not just financially but also in viewers’ and employees’ fulfillment. In focusing on tentpole films, Hollywood is only benefiting in the short-term, allowing younger companies with fresher content and happier employees to more likely dominate the market in the future.

In order to deconstruct its growing bubbling issue Hollywood must begin to embrace its behavioral economic counterpart, a concern that continues to give Hollywood’s key decision makers an implausible view of the future. As Spielberg and Lucas suggest, Hollywood is heading in a direction that permits itself in becoming an industry of spectacle at the expense of its traditional past and unknown future. It’s as if Hollywood today rests at a crossroads in having to decide which direction it wants to pursue; one that wishes to compete with more tech-driven companies in structure and content, or one that will capitalize on the making of big budget films perhaps to evolve in a Broadway-type model per Lucas’ prediction. At its surface, it seems pursing the avenue of spectacle would be the most plausible path for Hollywood to follow. However, the thought of Hollywood evolving into such a grandiose repetition is saddening, a reminder of the darker sides of conventional economics in blinding those so deeply involved with its numbers effecting the wider portfolio of films we used to expect from Hollywood. Yet conventional economics is not entirely the culprit, however it has been wrongly misused in the pursuit of making movies; it has been allowed to influence how an industry of cultural gatekeeping operates. If Hollywood embraced behavioral economics in addition to conventional economics, it would create a finer sense of equilibrium for its content, viewers, and employees involved. There are many solutions to the problem, but to be clearer as to how to incorporate behavioral economics – allow me to spitball an idea. To create a sense of equilibrium is to allow for the integration of a grandiose experience (say, IMAX), with films that don’t necessarily have to be of a grandiose nature. Let’s take Bird Man for example, one of the lowest grossing movies to ever win an Oscar for best picture. However, what if we had allowed Bird Man to run alongside an Avenger-type film, perhaps then we could experiment releasing a film of more artistic character with a film of more, let’s say, grandiose nature like any Marvel film. A film like Bird Man I’d argue would be awesome in 70mm, we just have to begin to incorporate such films with our growing technologies and not toss them aside; what if it didn’t win an Oscar? What would have happened to its reputation as a well-done, artistically-risky, original film? More tech-driven companies like IMAX and Netflix have grown exponentially in the last decade in large part due to their ability to more finely balance its System 1 and System 2, but it is still not too late for Hollywood to do the same.

[1] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow (p. 22). New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Ciroux.[2] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow (p. 200). New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Ciroux.[3] Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational (p. 8). New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers.[4] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow (p. 198). New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Ciroux.[5] Bond, Paul. “Steven Spielberg Predicts ‘Implosion’ of Film Industry.” June 12, 2013.[6] Ibid.[7] Ibid.[8] Ibid.[9] Eller, Claudia, and Richard Verrier. “Hollywood Writers Strike Ends.” February 13, 2008.[10] Eller, Claudia, and Richard Verrier. “Hollywood Writers Strike Ends.” February 13, 2008.[11] Ibid.

Companies

Aging and Nuclear War in the Writers’ Room

Have you ever heard of Hollywood, Health, & Society? Most likely not.

Yet, you have probably watched something that they have worked on. With over 1,100 aired storylines from 2012-2017 including those for Grey’s Anatomy, NCIS, and black-ish, Hollywood, Health, & Society (HH&S) serves to provide entertainment industry writers with accurate information on storylines related to health, safety, and national security. This pretty much includes everything from aging to nuclear war.

For example, that April 30th, 2017, episode of American Crime that included immigration, opiate abuse, and human trafficking in the plot? Data analysis is currently in progress for a cross-sectional study of viewers.

With the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center, HH&S not only pairs experts with writers, but also conducts extensive research on their impact and the correlation between seeing things on screen and audiences’ changed perceptions of those topics. HH&S maintains a low public profile, but is very much involved in the writers’ rooms and guilds. Their approach is two-fold:

1) Reactive – responding to requests and needs for HH&S services, which manifests in the form of phone calls and/or emails to the center, expert consultations, guidance on accurate language.

2) Proactive – introducing writers and entertainment professionals to subject matter experts through panel discussions, screenings and immersive events; a quarterly newsletter, tip sheets and impact studies.

Students, you are welcome to use this resource as well! HH&S serves writers at all stages of their careers, although of course, shows on the air or already in production have priority.

To learn more about the research and impact studies behind HH&S:

– Featured list of tip sheets for writers

– CDC’s list of tip sheets from A-Z

– On location trips for writers to gain understanding for certain topics

Follow Hollywood, Health, and Society on Facebook and Twitter to stay updated with their work and upcoming opportunities.

Companies

Social Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

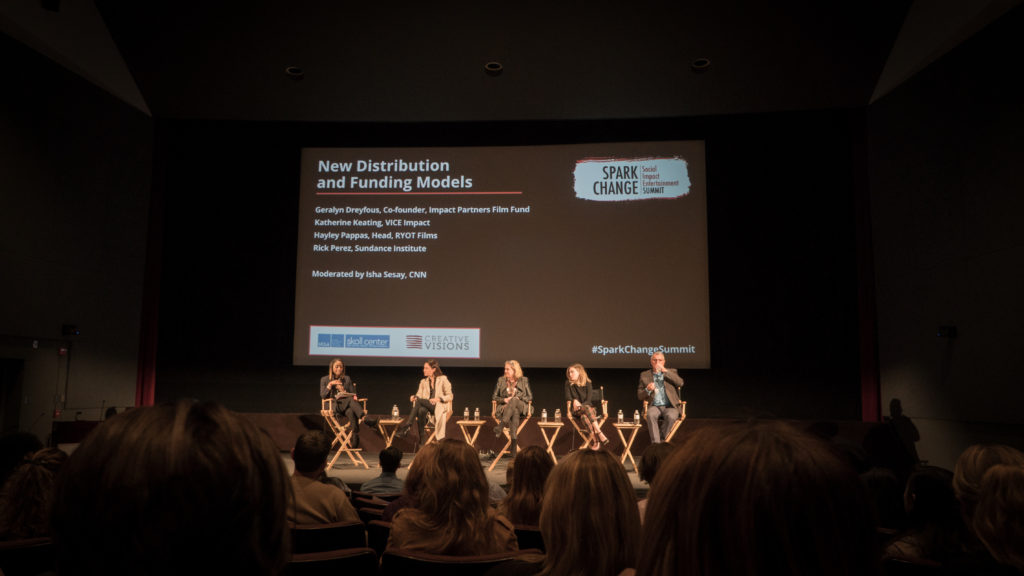

“Social impact entertainment’s time has come,” Teri Schwartz, the dean of UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television said as she welcomed everyone to the first Skoll Center summit. Nonprofit leaders, social campaign strategists, experts in distribution and funding, and a variety of creators gathered to define social impact entertainment, learn more about storytelling, and discuss new distribution and funding models.

Students and professionals alike joined in the conversation thinking about questions like: Is intention enough? What is the difference between storytelling and advocacy? What are examples of previously successful social impact campaigns and how can we follow those models? In this time of mass streaming platforms, how can artists market their social impact content and demand awareness?

The social impact entertainment field is developing, but very much alive. However, unlike industries that sometimes hide information to maximize self-growth, it is critically important for us to collaborate in this space and build a community of entertainment activists. Cinema of Change sent several to this summit to do exactly that: share what we’ve learned and be honest about what we don’t know yet.

So, what’s the secret sauce? How can films change the world?

Truth is, like the entertainment industry itself, there is not one path to ending climate change or human trafficking through film (unfortunately, I know). However, whether it is documentary, narrative, or docu-fiction, everything begins with storytelling.

-

STORYTELLING

No matter how important the statistics are or how beautiful the production design is, people are not going to watch a film that has no story. Sometimes, that is why a narrative film may even have a larger impact on a social issue than a documentary film because people relate and empathize to the fictional characters more and will walk away with those emotions in mind.

Holly Gordon, Chief Impact Officer of Participant Media: There’s a difference between storytelling and advocacy. Storytelling comes 100% from intention, but also creativity. “Creativity means intention and the ability to tell a story.” And that’s what leads to transformational change, which is long-term and visionary, compared to transactional change.

Hayley Pappas, Head of RYOT: As a reminder, “It doesn’t always have to be heartbreaking to be transformative. You can laugh a lot and see something in a new way.”

Davis Guggenheim, director of An Inconvenient Truth and He Named Me Malala: “Without the intention, you’re not going to do it. It’s too hard.” Documentaries can hit a wall sometimes because everyone working is so passionate about the topic, but when you go into the editing room, there’s no story.

As much as we support documentaries here at Cinema of Change, we also believe that mega blockbusters and social impact are not mutually exclusive. In fact, we wrote an article on exactly why we think the opposite here.

Darnell Strom, Creative Artists Agency: “Story matters. Representation on screen matters and that has a ripple effect.” Sometimes, filmmakers may not set out to have a specific intention, yet organic social issue campaigns arise from a great story. Take Black Panther for example. Disney probably did not set out to create a transformative piece about black culture through a Marvel comic book story, but the film had a majority black cast and depicted a woman leading the technological developments. Now, nonprofits are jumping up about women in STEM and young black boys and girls can watch the film and be like, Hey, if someone who looks like me can do it, so can I.

-

MEASURING SOCIAL IMPACT

Great, this film tells an incredible story about a disadvantaged youth rising from poverty and attending a prestigious university, but how do we measure the social impact? In other terms, how do we calculate the number of minds changed, or decisions made to take action? Even Gordon agreed that transformational change is very hard to measure, but it can be done.

Holly Gordon: For Girls Rising, which is both a film and nonprofit about the importance of educating young girls, measurement meant hiring Mission Management to analyze impact in three ways: changed minds (reach), changed lives (money raised), and changed policy (shifts in government policy). Gordon worked on relationship building with a number of nonprofits and even leaders like Michelle Obama to develop impact partnerships and shape campaigns around the themes in the documentary, before a single frame was even shot.

Rory Kennedy, director of Last Days in Vietnam and Ghosts of Abu Ghraib: Social impact is often thought of in large numbers: raising millions of dollars, changing thousands of lives, but it is also just as important on an individual level. For example, in Last Days in Vietnam, Stuart Herrington, a counterintelligence officer in the Vietnam War, was responsible for safely evacuating American soldiers at end of the war, but he knowingly left 422 Vietnamese soldiers there despite promising them safety. At the premiere of the documentary, Harrington reflected on his guilt and regret for leaving all those lives behind and said that he dreaded ever meeting one of the 422. Sure enough, one of the Vietnamese soldiers Harrington left walked up on stage and told him, “I forgive you.” That moment left both of the men in tears and it may not have changed a hundred lives, but it changed two.

-

IMPORTANCE OF SOCIAL IMPACT CAMPAIGNS

When a film wraps, the awareness and campaign work most definitely does not. Social impact campaigns are critical to accelerating awareness and creating a sustainable, lasting effect. They’re arguably more effective when launched before the film even begins production.

Bonnie Abaunza, founder of The Abaunza Group which has launched campaigns for The Hunting Ground, Hotel Rwanda, Cries from Syria: These impact campaigns are designed to intersect all industries and companies. Impact comes from educating students, mobilizing ambassadors, challenging companies, and partnering with nonprofits and policy leaders who care. One example of a highly successful social impact campaign is the one for Blood Diamond. Lena Khan, the director of The Tiger Hunter, even told Abaunza that she has a conflict-free diamond on her hand because of the film. Jewelry companies like Tiffany & Co. joined the movement by labelling their diamonds as “conflict-free” especially because more and more people started asking about it. Amnesty International created an entire curriculum to introduce the issue to students.

Ted Richane, Vulcan Productions Impact and Engagement: At the end of the day, “We can have our strategies, but the best thing we can do is listen. The community is awesome and going to be inspired and go to take the issue upon themselves.” That’s the ultimate goal, right? Launch the campaign, tell the story, and empower others to share and do something about it all.

-

DISTRIBUTING AND FUNDING SOCIAL IMPACT FILMS

The world of distribution and funding can be quite daunting to enter, because no matter how passionate someone is, it is always difficult to get the money needed to transform passion into action. Major companies are also a huge part of the conversation. How do they decide what films to green light? How can indie artists break out with both an entertaining film and one that creates change?

Geralyn Dreyfous, Co-founder of Impact Partners Film Fund: There is a shift nowadays in the distribution world. Only two films sold at Sundance this year. Netflix is commissioning their own content. Companies are not paying their creators enough, especially for short form content. To the artists: “You love it so much, you’d do it for free. But you have to stop doing it for free.” When starting out with trying to find investors, you can always pitch to the Impact Partners Film Fund, but if you’re not successful there, think about incentives and break up your budget into smaller chunks for financing. Can you give donors credits, on screen thanks, private screenings, and other benefits? “Mostly, founders are interested in amplifying and aligning your content with their philanthropic goals. They need to know that you’re the person to tell that story.”

Katherine Keating, Vice Impact: With a cross-platform company like Vice, it’s very important to think about who the audience is and where they are consuming their content. Some things are meant to be a series of five 1-minute shorts on Facebook, even though the artist may have pitched it as five 1-hour series. Another way to integrate the impact campaign is through brand partnership with large, respected companies. For example, Colgate, one of the biggest toothpaste sellers, is now promoting water conservation and looking at ways to reduce plastic use in their packaging. Companies are starting to recognize the importance of social impact and it’s our job as their commercial creators to push them in that direction.

Cinema of Change previously interviewed entertainment attorney Mark Litwak about the “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution”; read what Litwak has to say here.

NOW WHAT?

“To create in this chaotic world peace, to seek in this gathering darkness light, to transform the hatred into a new kind of loving. Together, we can transform this world. It’s going to be really hard. But we can do it, and it will be through storytelling and courageous people like you.” (Kathy Eldon, Co-founder of Creative Visions). With that, the SPARK CHANGE Social Impact Entertainment Summit came to end, but our work is just beginning.

As audiences, we have to demand for content that does not further marginalize communities and perpetuate stereotypes.

As companies, we cannot stay silent to the injustices in our world in order to protect our brand.

As filmmakers, we are not just producing beautiful, cinematic pieces. We have the responsibility to use those creations to spark change.

—

List of all organizations in attendance: Cause Cinema, CNN, Creative Activists Network, Creative Artists Agency, Creative Visions (co-host), Google, I am Jane Doe, Impact Partners Film Fund, Living on One, Majority Film, Participant Media (sponsor), President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities, RYOT, Skoll Center (co-host), Sundance Institute, The Abaunza Group, Vice, Vulcan Productions (sponsor) UCLA School of Theater Film Television

*Sayings in quotation marks are directly quoted. Other remarks are paraphrased.

Academia

Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

Welcome to the Cinema of Change podcast with Tobias Deml and Robert Rippberger. Cinema of Change is a magazine and community that challenges the conventions of film and its ability to effect change in the world. This episode is an interview with entertainment attorney Mark Litwak called, “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution.”

Mark Litwak is a veteran entertainment attorney. As a Producer’s Representative, he assists filmmakers in arranging financing, marketing and distribution of their films. Litwak has packaged movie projects and served as executive producer on such feature films as “The Proposal,” “Out Of Line,” “Pressure,” and “Diamond Dog.” He has provided legal services or worked as a producer rep on more than 200 feature films.

Litwak’s significance can be see in Disney’s Wreck it Ralph – where the filmmakers decided to name the owner of the arcade which encapsulates the entire plot, “Mr. Litwak”.

Content of this Episode:

- 0:22 – Introduction

- 1:33 – After learning filmmaking, what business pitfalls are common for young filmmakers?

- 5:15 – How is the Film Industry like the Wild West – creatively and in dealmaking?

- 9:11 – How can first-time filmmakers survive the Sharks in Sales and Distribution?

- 12:10 – Reporting the Bad Players: What was your Litwak Filmmakers’ Clearinghouse?

- 15:53 – CAM (Collection Account Management) – how do they help with accountability and fairness for the filmmaker?

- 19:52 – What happened to the Filmmaker’s Clearinghouse?

- 20:40 – Even Ethical Distributors will be out for their own best interest – is that true?

- 22:20 – What criteria do you base your client selection on? What homework should a filmmaker bring to a lawyer?

- 26:44 – How is New Media influencing the market and distribution?

- 34:38 – Can Indie Distribution even compete anymore with vertically integrated SVOD platforms like Hulu and Netflix?

- 39:03 – What progress can be made in the Filmmaker > Sales Agent > Distributor workflow?

- 42:44 – How can a producer put their best foot forward towards a lawyer?

- 45:50 – How can a filmmaker prepare for working with an Entertainment Lawyer?

- 46:46 – What resources exist in the film industry that even the playing field of sales and distribution a bit in favor of the independent filmmaker?

Litwak is also the author of six books: Reel Power, The Struggle for Influence and Success in the New Hollywood (William Morrow, 1986), Courtroom Crusaders (William Morrow, 1989), Dealmaking in the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 1994) (winner of the 1996 Kraszna-Krausz award for best book in the world on the film business), Contracts for the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 3rd Ed. 2012), Litwak’s Multimedia Producer’s Handbook (Silman-James Press, 1998), and Risky Business: Financing and Distributing Independent Film (Silman-James Press, 2004).

He is an adjunct professor at the U.S.C. Gould School of Law where he teaches entertainment law.

Litwak has a B.A. and M.A. degrees from Queens College of the City University of New York. He received his J.D. degree from the University of San Diego in 1977.

We hope you find this conversation interesting and insightful. Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss an episode. Until next time, be the change that you want to see in the world. Then turn it into cinema.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

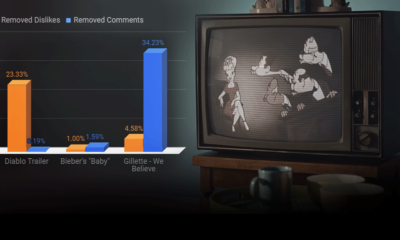

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films