Filmmakers

Framing the discussion of 50 Shades of Grey

Photo Credit: Universal Pictures and Focus Features

To say that it’s been hard to escape any mention of EL James’ juggernaut hit 50 Shades of Grey series is an understatement. Ever since March 2012 when 50 Shades of Grey first popped onto the literary scene at the top of the bestselling charts it’s seemingly become an juggernaut, continuing ever upwards with record breaking book sales and recently the first movie of a planned trilogy. The first movie of the trilogy, 50 Shades of Grey, was released February 13th to stellar ticket sales of 90 Million for the opening weekend and the two sequels were already in the works even before the premiere of the first film. Needless to escape any mention of it would require one to become cut off from all of society due to the extent the series has entered the mainstream dialogue.

The power the film wields on mainstream dialogue is unprecedented for a film adapted from such a source. The common attitude to the reading and enjoyment of erotica had been an implied social stigmatization that it was something to be hidden, yet at its height of popularity 50 Shades of Grey was being stocked in supermarket shelves and people were reading it at cafes and at bus stops. Now the movie is playing several times a day at your local movie theatre alongside other mainstream action, romance and kids’ films. Whether you’re against the series or for it the phenomenon of the 50 Shades of Grey movie has brought the discussion of the erotica genre into mainstream film for open debate and discussion.

After the initial success of the first book, 50 Shades of Grey , in 2012 the new word to enter the mainstream dialogue had been “Mommy porn”, a term coined to describe the assumed predominantly older female readership of the series and now film. The term had been sparingly used before this to refer to the stereotype of a middle aged housewife that lusted in theatres after the two hunks Edward and Jacob, of the source material for 50 Shades of Grey Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight but it is 50 Shades of Grey that has brought the term into the mainstream and arguably the erotica genre itself. This stereotype of the repressed housewife that cannot find any sexual solace except through her imagination and through reading highly vanilla romantic novels would do the books real women a disservice. Yet, why did this stereotype come to exist and dominate the conversation around 50 Shades and similar romantic series? The term itself lends to the social idea of an older woman being a sexless being once she’s had children or simply become older.

The disdain for “cougar fans” of the Twilight movies was a huge topic of discussion in the media that cropped up after each Twilight movie premiere and the release of 50 Shades of Grey in theaters has brought back up the discussion of “mommy porn”. Tied with this has been an unspoken condescension towards readers and the filmgoers that aren’t watching the movie for a joke. Everyone could read and watch 50 Shades of Grey til it became an accepted act but at the same time professing any sort of serious like of the series and by extension erotica was not acceptable. The social desire to relegate terms that lessen the desires of women and the media they consume created for women pervades the dialogue surrounding 50 Shades of Grey and its literary and film compatriots.

For background, before Stephanie Meyers decided to write about alluring vampires that sparkle in the sun and EL James decided a fanfiction about light BDSM could be her ticket to literary fame there were the bodice ripping Mills & Boon harlequin novels. Unsurprisingly these harlequin novels had always been advertised to be solely for women and as such were relegated to lesser form of literature. The defining feature of the erotica genre has always been that it’s a genre geared towards women and written by women.

This association within the social hierarchies relegated the erotica and romantic film genre to be considered a lower form of entertainment. Not even to be lumped together with the pulp novels of old that arguably were the same caliber of writing as erotica or even worse, erotica was a genre sectioned off on its own. It’s from this history that 50 Shades of Grey and its source material Twilight drew inspiration from but where Twilight censored the explicit details and only implied for mainstream commercial success 50 Shades reveled in it to puzzling mainstream success.

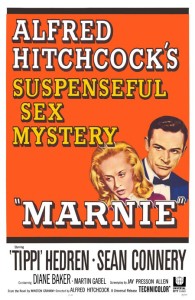

In Film,a legion of romantic movies depicting the naïve girl swept off her feet by a debonair older man have already been made for decades. There’s been a spectrum of the “love” story from the sweetly romantic to dark and forbidden. The classic psychological thriller Hitchcock film Marnie (1964), an apt example to highlight as a predecessor for 50 Shades as the plot of both films share man similarities. However in any discussion both films would be held to different standards. In Marnie a debonair businessman Mark, played by young Sean Connery, blackmails the femme fatale Marnie into marrying him as a way to rehabilitate her. The film plays out similarly to the entirety of the 50 Shades trilogy. Marnie is the Christian Grey to Mark as is Anastasia Steele in the plot of the film. Where Christian Grey is flawed and Ana seeks to rehabilitate him in his “unconventional interests” to become someone to love Mark also sought to rehabilitate Marnie from her’s. Both Christian and Marnie are scarred by their pasts and in both films it is through the sexual relationship that the two films chronicle that they are “healed”. Arguably both films have similar themes of the viewer as a voyeur into their lives as well but Marnie is considered a Hitchcock classic and 50 Shades of Grey is still a fad. While in his time Hitchcock was not an atypical filmmaker in the modern era his works are classics, with many holding his works to such a degree that it is said one could just learn film making from watching Hitchcock’s filmography. However despite other works sharing such similarities to the themes of his works to other works of similar themes many are not held to the same standard. Erotica and fiction of women as freely sexual beings is still considered a fad interest that could fade from mainstream discussion.

In Film,a legion of romantic movies depicting the naïve girl swept off her feet by a debonair older man have already been made for decades. There’s been a spectrum of the “love” story from the sweetly romantic to dark and forbidden. The classic psychological thriller Hitchcock film Marnie (1964), an apt example to highlight as a predecessor for 50 Shades as the plot of both films share man similarities. However in any discussion both films would be held to different standards. In Marnie a debonair businessman Mark, played by young Sean Connery, blackmails the femme fatale Marnie into marrying him as a way to rehabilitate her. The film plays out similarly to the entirety of the 50 Shades trilogy. Marnie is the Christian Grey to Mark as is Anastasia Steele in the plot of the film. Where Christian Grey is flawed and Ana seeks to rehabilitate him in his “unconventional interests” to become someone to love Mark also sought to rehabilitate Marnie from her’s. Both Christian and Marnie are scarred by their pasts and in both films it is through the sexual relationship that the two films chronicle that they are “healed”. Arguably both films have similar themes of the viewer as a voyeur into their lives as well but Marnie is considered a Hitchcock classic and 50 Shades of Grey is still a fad. While in his time Hitchcock was not an atypical filmmaker in the modern era his works are classics, with many holding his works to such a degree that it is said one could just learn film making from watching Hitchcock’s filmography. However despite other works sharing such similarities to the themes of his works to other works of similar themes many are not held to the same standard. Erotica and fiction of women as freely sexual beings is still considered a fad interest that could fade from mainstream discussion.

Does the new 50 Shades of Grey movie being in the mainstream discourse make it a ground breaking and a victory for feminism, because it has a female director and female protagonist, as it has been touted?

I wouldn’t agree.

Many other works of the same genre of higher caliber have had a female protagonist and presumably could have a female director if adapted for a film as well.

Is it feeding into a history of similar story tropes in the erotica genre that reflect back the social dynamics of sex that women navigate every day?

Yes.

Our every reaction is a reflection of the social structures we live and navigate in. 50 Shades of Grey will never be a masterpiece but it could be a catalyst for discussion. If 50 Shades of Grey is a joke and a fad, what relegates it to such when similar works have been gifted with the designation of “classic”?

What 50 Shades of Grey has done is create a new stream of open mainstream conversation around the traditionally stigmatized women dominated genre of erotica. The story itself isn’t innovative or anything different from other erotica novels but it is different for being chosen to be accepted into mainstream media. It is important to look at what has led to the film because with the commercial success of the first 50 Shades film there is certainly going to be a clamor for the next great erotica film. The next money maker now that the erotica genre has opened up to become a viable source of money. That “female entertainment” is not just for women after all. Making sense of the underlying factors of the discussion now will have to prepare us to better understand in the future when we could be having the legion of copycats parading through the theatres.

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

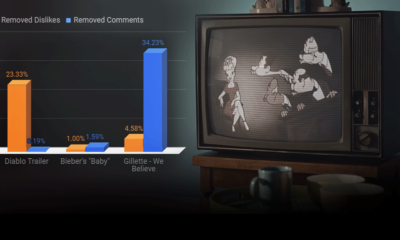

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films