Academia

Film Theory 101: Understanding Benjamin, Metz, Kaplan via Lindsay Lohan

Either you clicked on this article because you took the title’s bait or you genuinely seek to learn some film theory. My goal in doing this is not to bore you, but to hopefully have you retain something in comparing theories to Lindsay. Let’s dive into this: there are many mediums of art that try to capture life, varying expressions or some kind of phenomena, typically through the work of one artist. Film, however, challenges these philosophies in that it is a medium of art that arguably attempts to do the same thing, but due to its technological nature, and its production process, sometimes falls short when compared to the qualities we find in other forms of art. Film theorists have tried to simplify (or, complicate?) the true nature of cinema and where it lies in terms of its other artistic counterparts.

Walter Benjamin was a theorist whose ideas were based on film and its relation to the screen, Christian Metz focused on individual spectators, and Ann Kaplan theorized about society and how it reflects the films we watch. We will explore their theories and elaborate on which of these three theorists offers the best road map for understanding film and its impact in our world. In doing so, I will endeavor to make these topics less dense and compare theory with popular culture (we love you LiLo).

Walter Benjamin

Walter Benjamin (pronounced ‘ben-na-meen’) was a theorist with interests that focused on the ‘reproducibility’ of film, the representation of human beings on screen, and how these ideas demonstrated the ever-changing human perspective. Benjamin makes a convincing claim in that his theories ask the question of, why film can be like any other form of art if the core of its existence relies on it being reproduced. He uses the screen as a way to theorize his beliefs on the essence of cinema and how it derives from formal conventions and technologies. Where pieces of art like the Mona Lisa – if reproduced – would lose their prestige compared to film as an art form. Benjamin writes in regards to these forms of art, “It is this unique existence – and nothing else – that bears the mark of the history to which the work has been subject.” What he is saying here is that the whole sphere of authenticity eludes technology, not only that, but technological reproduction strips away the aura that exists within traditional art. Yes, Benjamin would really hate snapchat. Benjamin believes that stripping away this aura and producing massive amounts of art creates a sense of sameness in the world, extracting what is unique while taking away an appreciation of its historical context (let that sink in…)

Benjamin goes on to discuss the role of actors and their relationship on screen through their connection with technological apparatuses – he points out that actors on screen are aware of these apparatuses, and the fact that they are recording what will be displayed for the masses. This puts actors in vulnerable position as Benjamin writes, “It is they [the audience] who will control him [the actor].”

To Benjamin’s point, Lindsay Lohan finds/found herself in an almost parallel position to that of the actors that he describes. The paparazzi’s addiction to publicizing her life in the early 2000’s (and your unwavering desire to follow her life) put Lohan in a position where she’s aware of the fact that these photos will be shown to vast amounts of people, which put her in a vulnerable situation – yet she continued to behave in ways that drew what seemed to be undesired attention on her part.

Christian Metz

Metz takes a rather psychoanalytic approach as to why people enjoy going to the cinemas and seems to ask, what is it about the cinema that is so intriguing and why do so many people devote their time and money to watch a film? (It’s a valid question!) He focuses on the individual spectators and what their physical and psychic structures bring to the films they watch. First, Metz believes that we go to the cinema to participate in a voyeuristic gaze and to fulfill this desire of being able to look without being looked at. Metz believes that a component to all films is the subjectivity the audience derives from decoding the meaning of the film. Throughout our time in the cinema, we identify with the camera as it fulfills our desire of allowing us to look into a life unlike our own. If we did not attempt to identify with the film, Metz writes, “…film would become incomprehensible, considerably more incomprehensible than the most incomprehensible films…”

This too, is similar in what we see with people’s desire in publicizing the life of Lindsay Lohan (and Kanye and Miley and Biebz and Zuckerberg). The tabloids have made it simple for us to look into the life of a celebrity never having to experience any kind of consequence. Like the actors on screen, Lohan fulfills this desire of providing people with this sense of; ‘I’m glad that’s not me, but god this is gold’ mentality – or “schadenfreude.” This leads to the next question of why we enjoy peeping into the lives of these non/fictional characters. Metz believes that when we go to the cinema we are given this false perception of reality. Metz links this phenomenon to the idea of the mirror stage, a concept of Lacan, and challenges this in saying that films work less like a mirror and more like glass. He challenges Lacan’s theory because he believes that spectators have already experienced the mirror phase in their personal lives, so they are able to constitute and relate to everything that is already within the film. Thus, he rejects the notion of the mirror stage within films because he believes that the only things not reflected in films are the spectator’s bodies themselves, consequently becoming a clear glass rather than a mirror.

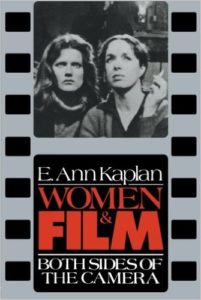

Ann Kaplan

Ann Kaplan, like Metz, was interested in the psyche and nature of the spectator believing that Hollywood acted as a portal to our “patriarchal unconscious”, which could be decoded through psychoanalysis. However, Kaplan was concerned with the intended gaze that films put on their audience and challenged many feminist film theorists’ ideas of the masculine gaze, including what this said about society. Unlike Benjamin and Metz, Kaplan was concerned with the social forces that help shape the collective medium of film. Most feminist film theorists pointed the finger at Hollywood and how many narrative films since their inception were highly masculinized – producing films with predominant male gaze while objectifying women and using them largely for sex appeal. Kaplan, although she agreed with this notion, challenged the definition of the male gaze. She believed that although a male gaze exists in almost all films, it is rather a question of dominance versus submissiveness, and any actor, be it male or female, can participate in these roles. She writes, “we need to analyze how it is that certain things turn us on, how sexuality has been constructed in patriarchy to produce pleasure in the dominance-submission forms, before we advocate these modes.”

She uses John Travolta as an example in that in many of his early films he, as she points out, played a submissive role (Urban Cowboy anyone?). This put female spectators in the dominant position allowing them to participate in this supposed masculine gaze. She points out that just because the gaze is masculine doesn’t mean it’s meant for men, but instead there will always be a gendered gaze inverting this innate hierarchy. In the case of our girl Lindsay, Kaplan would undoubtedly argue that she is objectified through tabloids and other sources of mass media. Lohan, like the idea of male dominance, is a construction of western society and the pressure put on celebrities might explain her irresponsible lifestyle. Lohan, to Kaplan, is neither a victim of male or female gaze but instead a victim of societal gaze as it seems that she is being used as an example of the negative impacts of, in her case, being a celebrity… and we see it time and time again, sadly/ironically to very people who work to entertain us.

Although each of these theorists offers an insight into film, Walter Benjamin is the theorist that in my opinion offers the best road map to understanding film and its relation to the world (big ‘effing statement, I know); but I chose his theory because of Benjamin’s explanations of the actor and the ‘reproducibility’ of film, which is on par to Lohan’s situation. Benjamin is the only theorist to point out the noticeable amount of pressure an actor endures while subjecting themselves on screen for the masses, knowing that it could potentially cause criticism that could make or break their career. Benjamin would argue that the reproduction of these largely negative tabloids have without a doubt caused Lohan’s (and seriously every other living actor) personal life to be put onto display and for her overall credibility, or arguably her aura as he might say, to be challenged as an actress going forward. I think many of us would agree, Mean Girls was sort of the last of Lohan’s best.

In the end, Benjamin, Metz, and Kaplan are theorists that share a passion for film but take a different approach on their insights to the overall essence of cinema. With the help of Lindsay Lohan, I hoped to have demonstrated only a portion of these theories via the intricacies of our pop culture.

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

Media Impact

Can We Believe The Gillette Ad?

The new Gillette Ad. It’s Pepsi #2. It’s poorly executed, laden with half-hearted strategy, an elephant in the China shop of gender relations.

Numerically speaking, it’s not what it seems to be either. 34% of the ad’s comments were deleted, far more than other videos in similar dislike territories. Gillette’s account might just have set the YouTube proportional record for deleting comments on a single video (the absolute record goes to YT’s own Rewind 2018).

Taking Count – What Numbers Are Real on YouTube?

There have been repeated claims, mostly by YouTube commentators, that dislikes and comments were deleted. Another claim group was that the proportion of likes to dislikes seemed manipulated since it changed from a 10:1 ratio to a 2:1 ratio within days. Some outlets picked up the story, but nobody dove much deeper than a few screenshots. Well, after a few days and 3.000+ measurements we have answers for you.

With the help of YouTube’s API and Archive.fo’s screenshots of the video’s public numbers, we were able to test the claims of whether Gillette’s dislike and comment count were being subject to unusual moderator deletion.

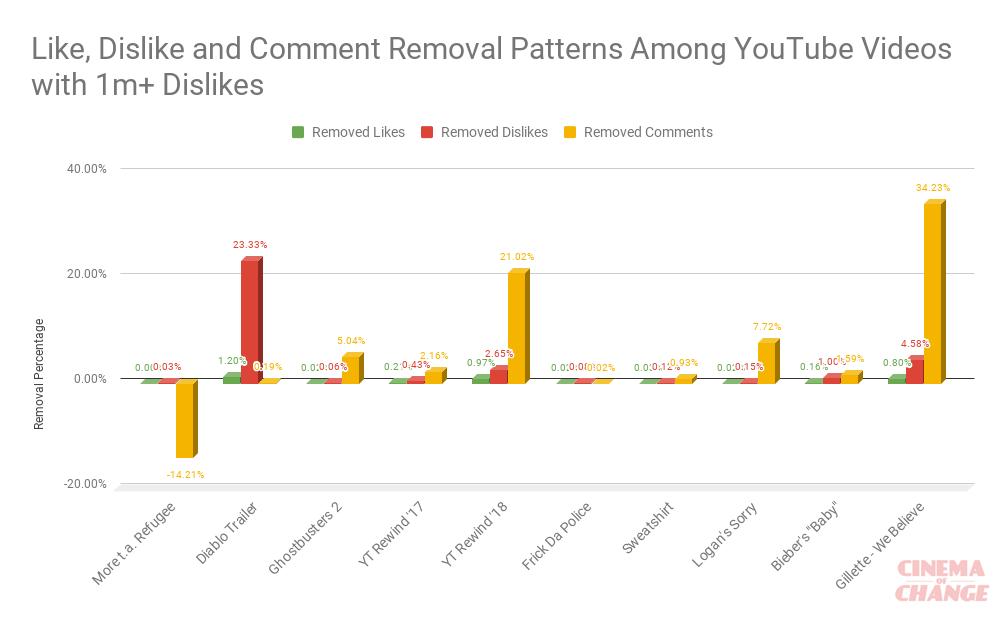

Before we ask that though, it’s important to know how much moderation usually goes on in other controversial videos. If it’s common to delete a certain amount of comments/dislikes, then the criticism of Gillette isn’t directly fair – it’d just be part of the YouTube ecosystem. To get a litmus test of “how common is comment/dislike moderation in similarly controversial videos”, we used a few close neighbors in the List of most disliked YouTube videos as comparables and measured the front-end/back-end discrepancy.

One of them was a “Diablo” game trailer that also received criticism that the publisher had deleted comments and dislikes. Our research was simple – we made API queries to YouTube’s server back-end over the course of a few days while manually transcribing screenshots of the front-end from Archive.fo for similar time spans. While YouTube’s server keeps all video interactions on record, even fraudulent or bot-based ones, the public front-end is influenced by a filtering mechanism that hides certain interactions.

Claim 1: The Gillette Ad Had A Manipulated Growth Pattern

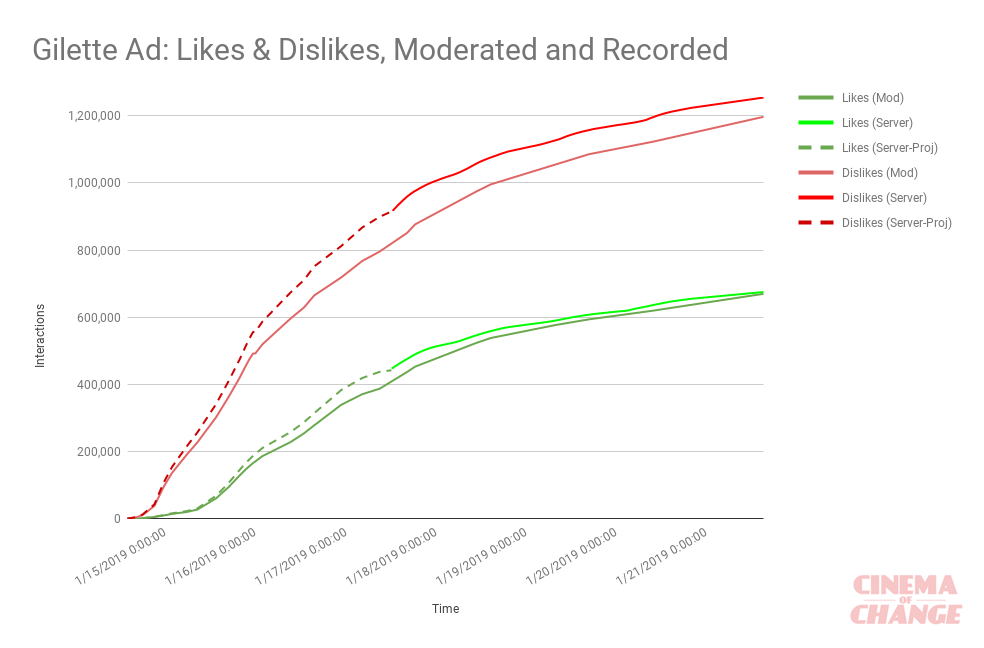

There was nothing really unusual about the growth pattern of likes and dislikes in the Gillette video while we were measuring it. But we started measuring server data on Day 3 of the video being public – the first 3 days we only know from public screenshots, and can project how the deletion pattern must have created a difference.

The growth and change of server-side as well as public facing likes and dislikes on the Gillette “We Believe” ad on YouTube.

You can see that in the beginning, dislikes took off very quickly, while likes had a slower growth, but eventually the growth rates approximately equalized, so now there’s a constant 500k lead on dislikes to likes. This is a simple explanation for the changing ratio from 10:1 to 2:1, and we have reason to believe there was no foul play at work there.

Interestingly enough, while there are more dislikes than likes that were hidden by moderators, the likes count disparity shrinks as time goes on, essentially un-hiding likes again. This might be a technical glitch, since a similar shrinkage of hidden dislikes seems to be going on as well.

The archival data only records public likes and dislikes, not comments – so we aren’t sure about the comment deletion pattern over time.

Like data? Take a look at the public spreadsheet.

Claim 2: A High Number of Dislikes and Comments Were Deleted

What was far more surprising to see was the comparison to other highly disliked videos. The server queries resulted in two real outliers – Diablo’s massive deletion of dislikes, and Gillette’s outstanding number of comment deletions. While Blizzard eradicated 220k dislikes on its Diablo Immortal trailer (that’s 23% of the total) from public view (Gillette only deleted 5%, slightly above average), Gillette deleted a whopping 34% of its comments – 172,000 comments to be precise. This is closely followed by YouTube’s own 2018 Rewind video, which has 21% of its comments removed and is the most-disliked video in YouTube history.

Gillette deleted a potentially historic fraction, 34%, of its comments on the “We Believe” video. Blizzard removed 220,000 dislikes on its worst received game trailer, and YouTube banned 21% of the comments on the latest Rewind video.

Here’s the underlying spreadsheet for that data.

There’s a reasonable argument that the comments on Gillette’s ad were so hateful that they had to be deleted, and the primary fuel to that fire would be the implicit attack on men in general, or the explicitly feminist message. The argument is solid when examining anti-feminist culture on YouTube; Feminist Frequency has their comments and likes disabled since the Gamergate controversy (also on server side), the most-watched pro-Feminist video is a TED Talk and has about 3,000/15% of comments deleted. Then again, semi-viral videos that would fit the “men will feel uncomfortable” category, like the Billie Bodyhair campaign or 10 hours of walking in NYC as a woman or #ustoo PSA, don’t have strong deletion patterns (approx. 1-2%).

If we want to know why Gillette proportionally deleted more comments than anyone else in that league, there’s only one way to know: For Gillette to give the public some insights in what their deletion policies looked like.

Note 1: “More than a Refugee” somehow has more comments publicly displayed than the server-side API query counted – I’m not sure how that’s even technologically possible.

Note 2: After talking with a number of large-channel YouTube managers, I was told that it was not possible to delete dislikes. Well – Blizzard’s 20% dislike deletion shows that YouTube makes exceptions.

Not Just Numbers – Let’s Talk Impact

After analyzing the numbers on YouTube engagements, the question to ask is: How did this happen? Why was the blowback so severe? Gillette was in a unique position to turn the gender relations conversation into a very engaging campaign that would have mobilized people positively. But they didn’t. Instead of focusing on progress, they focused on ambiguous, polarizing messaging.

In short, the “We Believe” ad was a waste of Gillette’s potential. And here is why.

I am all for purpose-driven marketing. I spend day and night thinking about and actually producing impact-driven content. And when that kind of advertising is done right by big agencies, it’s really quite incredible to watch positive impact unfold.

Well-Executed Campaigns as Primers

Take the Kaepernick ad by Nike. It asks people to dare to “dream crazy”, and took a political stance against the oppression of black people in the U.S by featuring Colin. That gamble played out well; the backlash was outweighed by support, and the market responded positively for a good run.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq2CvmgoO7I

.

Or remember the Winter Olympics ad, “Proud Sponsor of Moms”? Guess who did that. P&G, parent company of Gillette. Everyone loved that. And in case you don’t watch much advertising, they did more of those, with bold themes and increasingly diverse casting.

P&G followed it up by tastefully celebrating black people’s identity and appearance with “Dear Black Man”:

.

Patagonia didn’t even use a video – they just turned their website dark and said “The President Stole Your Land” as a response to Trump’s threatened shrinkage of National Parks, and then sued him. The market liked it.

There are countless other examples of brands choosing more aware, purpose-driven marketing campaigns.

Watch at least a few of those above to get a primer of “what works”.

What all of them have in common is that they picked an impact area that was either agreeable to most their viewers, or close enough to their company ethos that controversy wouldn’t erode their loyal, primary customer base.

How Not to Do It: Gillette Ad & Pepsi Ad

Now compare this with the below:

Pepsi – “Jump In”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dA5Yq1DLSmQ

Gillette – “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPmuEyP3a0

.

Pepsi co-opted a social movement with a reality TV character and then preached unity when the world looked starkly divided. And even though some Pepsi drinkers might also watch the Kardashians, they saw through the half-hearted charade: Pepsi had nothing to do with activism, period. It was an “out of the blue” decision to capitalize on something happening in the world, and it felt fabricated.

Gillette did the same. Gillette has nothing to do with feminism, or with anti-bullying. Someone at Gillette decided to make this a cause out of the blue.

Gillette co-opted legitimate movements and issues like #metoo, but instead of sheepishly celebrating a soda version of a harsher reality like Pepsi did, it opened with s bad apples as representatives of its core base without delineation, and then sprinkled in a sugar coat of suggestions for all men on how to be better. Nothing new there, it’s just political now.

As a reality check, “toxic masculinity” is a pretty confusing nomer for negative aspects of masculinity. A Gillette ad for women opening with “Abusive women” wouldn’t work just like a US Army ad opening with “Un-patriotic Americans”. The conflation of two words creates ambiguity outside of an academic debate – is the adjective-noun pair describing the quality of the noun, or is it referring to a sub-part of the noun that matches the adjective? To further go into a grey zone, the “toxic” voice over is largely drowned out by “harassment” in the ad, resulting in a “sexual harrassment masculinity” sound upon first listen.

We’re not on a college campus dissecting word pairs here – we are in the world of impact-driven advertising to mass audiences, and you can’t afford ambiguity in this arena. Anyone that looks past these sloppy linguistic choices is providing Gillette a biased playing field.

.

The rest of the video is full of caricatures of bad men mixed with normal men, and an eventual return to “being the best”.

But by then, the base has tuned out, and Gillette has lost. Not only many of their customers, but an opportunity: To actually reshape and contribute to masculinity. To actually make an ad that men will watch, will love, will share, and will actually make them better men. An ad that all men can agree with, without reservations. An ad that doesn’t open with bad apples as representatives. An ad that encourages men to be present in their boys’ lives. A campaign against bullying.

Something that every man can stand behind, and a standard that we’re all proud to live up to. But that chance was wasted for something phony.

Gillette’s skin-tight ads in 2011 remind us of what the brand used to think about women – and how it appealed to similar sentiments it now criticizes, without acknowledging the hypocrisy.

Looking Inward and Forward to Do Better

Why do so few see the charade here?

Gillette could have acknowledged its treatment of women for the past 100 years and apologized, if they wanted to. Nobody really seems to see the irony in applauding to the feminism of the ad and Gillette’s unacknowledged past in contrast.

How about something as complicated as implicit biases by men (like what the boardroom scene tried to address)? Well, they could have done a boy’s version of their Always Ad #LikeAGirl (it’s a bit clunky but the idea is highly effective, and I’m sure it’d have worked with boys too).

All these topics take time and care to implement in separate campaigns. Gillette’s current ad is the impact equivalent of a “YouTube Rewind”, and is heading into similar mashup-dislike-count territory. There have been prior (Harry’s) and later (Egard) attempts to make “men’s issues” themed feel-good ads, but nothing comes close to the “primer” ads on the top, which had an impact edge to them.

A new Adweek Article suggests that the ad was primarily meant for women in the first place, to change their perception of shaving from “disgust” to “joy”. It’s a bit questionable to criticize men as a vehicle to position the brand better for women.

Doing ads that honestly criticize without alienating – that is hard. To Gillette’s credit, they at least failed at something challenging – and that is brave.

Non-Profit Tie-Ins Need Care, Not Just Cash

To finish on a slightly hopeful note – it’s wonderful that Gillette decided to donate $1M to the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Awesome. But that’s all that Gillette had to say on their new thebestmencanbe.org website. No roll-out, no strategy, no content, no pipeline – just a promise of money and a single link to a great nonprofit. That’s the laziest impact follow-through effort I’ve seen in a long time. Sloppy ad, good nonprofit choice, obvious lack of involvement in the actual impact.

Gillette is a big company, and they can absorb a blow. 1.1M dislikes on YouTube isn’t even close to what Justin Bieber gets. But unlike Gillette, Bieber’s team left the negative comments rather untouched.

.

In the world of purpose-driven advertising, I like to hold companies, agencies and decision-makers to higher standards. Not a peer-pressured applause for intentions, but well-earned respect for nuanced execution and actual impact.

Because we all can be better.

And Gillette should be the best they can be.

Companies

Aging and Nuclear War in the Writers’ Room

Have you ever heard of Hollywood, Health, & Society? Most likely not.

Yet, you have probably watched something that they have worked on. With over 1,100 aired storylines from 2012-2017 including those for Grey’s Anatomy, NCIS, and black-ish, Hollywood, Health, & Society (HH&S) serves to provide entertainment industry writers with accurate information on storylines related to health, safety, and national security. This pretty much includes everything from aging to nuclear war.

For example, that April 30th, 2017, episode of American Crime that included immigration, opiate abuse, and human trafficking in the plot? Data analysis is currently in progress for a cross-sectional study of viewers.

With the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center, HH&S not only pairs experts with writers, but also conducts extensive research on their impact and the correlation between seeing things on screen and audiences’ changed perceptions of those topics. HH&S maintains a low public profile, but is very much involved in the writers’ rooms and guilds. Their approach is two-fold:

1) Reactive – responding to requests and needs for HH&S services, which manifests in the form of phone calls and/or emails to the center, expert consultations, guidance on accurate language.

2) Proactive – introducing writers and entertainment professionals to subject matter experts through panel discussions, screenings and immersive events; a quarterly newsletter, tip sheets and impact studies.

Students, you are welcome to use this resource as well! HH&S serves writers at all stages of their careers, although of course, shows on the air or already in production have priority.

To learn more about the research and impact studies behind HH&S:

– Featured list of tip sheets for writers

– CDC’s list of tip sheets from A-Z

– On location trips for writers to gain understanding for certain topics

Follow Hollywood, Health, and Society on Facebook and Twitter to stay updated with their work and upcoming opportunities.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films