Films

Distorted screens: the false connection between deformity and crime

Through the dark and damp corridor she sneaks away, fearing and shivering, sweating and crying. Something is hunting her, a creature that knows how to move underground, who inhabits the sordid world that is below. Something powerful with rusty and large weapons, born already with the instinct of chasing, mutilating and killing. She turns around full of panic, and there it is: a big and deformed thing that does not deserve to be called human, grotesque body full of lumps and covered with filthy rags. A malformed existence that only lives to open wounds into the clean, peaceful and well-balanced reality of those who reside on the surface. She screams, but her voice is soon drowned by the blood that floods her throat.

What I described could pretty much summarize the plot of dozens of terror movies, especially those of the slasher and gore subgenres. But even more specifically it could fit the storyline of what should be also considered a whole subgenre by itself: films about disfigured or disabled evil people. The list of titles could occupy the whole article, but it is enough to say that some of the most famous killers onscreen were affected by some kind of mental and/or physical handicap or deformation: Jackson, Leatherface, Freddy Krueger, and many more (including all the main antagonists in the The Hills Have Eyes series). Whatever the reason that pushes them to crime (pure instinct, social rejection, family manipulation, revenge, etc.) their looking and ‘awkward’ behaviors are used as visual ways of accessing to their dark soul.

The cinematic use of deformations both of the physical appearance and mental states is as frequent as misleading. Deformed bodies, difficult speech, strange movements of the limbs, all are used as visual means to reinforce or directly signify the ‘there is something really wrong with that person’ idea, through the pure image. Nonetheless the link established is not natural, not real.

That association between body dysfunctions and criminal or violent behaviors is a simple fallacy: disabilities and physical handicaps don’t lead to crime. These are biological conditions, while crime is a social problem. However, believing in that connection has been one of the repeated obsessions of many criminologists, like the infamous Cesare Lombroso, self-proclaimed ‘scientist’ (though his methods did never accomplish the scientific model) who proclaimed that facial ‘animalistic’ looks indicate a genetic predestination to crime. Such a statement has always been rejected by the bulk of the scientific community, and never proved by its promoters.

Audiovisual media needs to find ways of converting abstract concepts into the specifics images we as spectators are going to watch. Choosing to signify criminal conducts through physical attributes becomes troubling when considering that the social understanding of crime is nowadays mainly conformed not by justice institutions (such as police and courts), but by mass media. There is then a responsibility towards the public, an ethical duty for cinema creators and distributors. We need to be conscious that the visions of crime movies transmit are going to be, together with the ones that TV broadcasts and Internet spreads, the ones that will crystallize in the common imaginary.

The risk then is to use these features in a way that is insufficiently justified by the plot, to display those characteristics as a lazy and unimaginative resource to augment the fear or disgust of the audience, without critiquing or commenting on the real reasons behind the criminal acts of the characters. It is cinema professionals’ task to endorse through their movies a discourse that doesn’t stigmatize disabled people, labeling them as prone to crime when there is no evidence of that. This brings into my mind the ending of 8mm [SPOILER], when Nicolas Cage’s character Tom finally unmasks the snuff films killer, and discovers that the face he and the audience were willing to see has no malformation, that the feared criminal mind was not a disabled or challenged one, as he expected. Tom looks at him with incredulity, as the killer finally states: “What’d you expect? A monster?”

Films

An Infinity War Review, or A Marvel Cinematic Universe Retrospective

1) The Russo brothers have created Marvel’s best directed film.

2) This film is Marvel’s most important development since the original Avengers.

The Origin Story

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has always been an ambitious project. No other franchise had ever successfully created a cohesive universe like this. But with that, Marvel Studios realized the unique challenges they would need to overcome to maintain their cinematic world.

Steven Spielberg once claimed that audiences would grow tired of comic films, and that they would go the way of the Western. Although I love Marvel’s films, I once agreed with Spielberg’s sentiment. Each premiere brought the question back into my mind: “Is this where the downhill trend starts?” Several times, I walked out of the theater thinking “yes.” Only for the next release to prove me wrong.

The comic book movie is not a genre anymore. The tropes that defined comic films through the early 2000’s hardly exist today. The only aspect that defines these films today is an incredibly rich catalog of source material. A source material that has been reshaped and reinterpreted countless times over several generations. These characters are timeless; they represent the ideologies of previous generations, yet are constantly developing to the present day climate. The MCU is the newest interpretation of this modern mythology.

Over the last few years, Marvel’s film-making experiment started tackling issues like government oversight, mental health, institutional racism, and more. Moreover, these films started adapting established genres (political thriller, space opera, heist flick) to the comic book “genre”. This could only be done because of talented directors who respected and understood the source material. Marvel was learning how to make different types of films with their properties. They helped to deconstruct the comic book genre and laid the foundation for their franchise’s longevity.

While Marvel’s individual films could thrive by adapting their source material into genre films, the team-up films (The Avengers, Age of Ultron, and Civil War) were still finding their footing.

The Avengers (2012) was groundbreaking. It showed that the Marvel’s bets could pay off, but it also showed everyone the problems they would need to overcome. This film spends a lot of time setting up the team, and for a majority of the run time, the Avengers are learning how to work with each other instead of working against the primary antagonist. More than a few characters were pushed to the wayside as well. In the end, the film was only about establishing the Avengers as a group, not developing that group as one entity. Regardless, the film proved that team-up films could work and more importantly, set up the future development of some of its key players.

The Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015) might have been a much better film if Marvel decided to make it an Iron Man film with Avengers as side-characters, similar to Civil War. At its core, Age of Ultron wanted to be a film centered around Tony Stark and his reflection, Ultron. But there wasn’t enough time. The solo film’s formula could not work in the Avengers films. And with the Avengers together from the start, director Joss Whedon struggled to develop each individual and the group as a whole simultaneously.

The Avengers showed audiences a tease of what team-up films could accomplish, but there was no precedent for developing the entire group over a full feature. Consequently, Age of Ultron showed how difficult that task was. Civil War was successful and well-received, but it was centered on Captain America while the rest of the Avengers took a backseat.

Enter The Avengers: Infinity War (2018).

The Review

What makes a film good? What makes it bad? How much of that judgement is determined from objective metrics and how much of it is influenced by context?

Genre does not excuse poor storytelling. “It’s just a comic book movie” cannot be an explanation for a film’s shortcomings. But genre, background, and source material do provide a context to judge art mediums appropriately. Metrics of quality adapt to new art, not the other way around. We don’t criticize The Odyssey or Gilgamesh for plot holes; we accept them as part of the story and we realize that much of those stories’ impact wouldn’t be possible without their faults. Stories are a product of their time, and they can not all be judged on the same rubric.

Adaptation needs to occur on both sides. As much as source material needs to be changed to fit into the medium of a film, film as a creative medium should adapt to comics.

Infinity War hopes to define the future of team-up superhero movies. The Russos are outstanding directors and they know the technical faults of this film better than anyone. But direction is about choice. What did this film choose to sacrifice to create what it did?

Infinity War challenges the audience to keep up. Modern film making has been hijacked by today’s media consumption. Binge culture has changed how audiences watch media. Infinity War is a film that can assumes you have kept up, because it is so much easier to do so today than it was 20 years ago. And that assumption allows it to explore a story on a larger magnitude without worrying about set-up.

Although the MCU is a series of movies divided into phases, we should not think of the Avengers films as finales to television seasons. They signal the start of a new development, not the end of the current one. Most main characters in this film have completed their character arcs before the movie begins. The Avengers films are about conflicts whose aftermaths set our characters on a new journey. Because there is so little screen time for so many people, the best way to develop our heroes is to use the team-up films as a starting point for each character, not as a conclusion.

Many characters lacked satisfying arcs because their arcs don’t exist in this one film; they existed in the films leading up to it. Giving meaningful presence to each character is an act of futility; it eats up too much time. Instead, Infinity War takes these fully developed characters and begins pushing them to their limits as a group.

Infinity War isn’t about watching these characters change and evolve; it’s about showing how these characters haven’t grown enough. The Avengers, as a group, have not developed properly in the past 6 years. From that, the ending of this film punctuates how these characters need to grow to move on. Our heroes needed to have a definitive loss. And we all need to let that sink in. Infinity War acknowledges the character’s and the franchise’s faults and sets them on a path to resolve them. We leave thinking less about the movie and more about how it fits in to what came before and what is coming next.

The Aftermath

Art always adapts to its current audience; our support and criticism shape the evolution today’s media. Our biases are rooted in the past and, consequently, our expectations as well. Although we are inspired by the past, we cannot push art forward with breaking the status quo.

The MCU is not a film series. It is a web of interlocking stories; a living project that grows and develops alongside it’s audience. There are endless branches of stories and events that intersect, combine, and grow together. It is the closest any medium has gotten to becoming a comic book series (shocking, I know).

Infinity War was never trying to be a good film. A film like this can’t spend its time adhering to conventional views on what a film “should be” because it is spending its time trying to push those standards. It is a film that puts traditional structures aside because it can rely on the structure of the franchise. It can set aside establishing characters because the audience knows them already. The title of this entire article summarizes my main point. You cannot speak about this movie without speaking about the franchise as a whole.

Infinity War is the best directed film in Marvel’s Cinematic Universe.

As a film, it’s not perfect. Some could probably make a good argument that it is a bad film. It has issues ranging from pacing, character arcs, etc. But Infinity War, and the Russos, are very aware of that.

Infinity War suffers as a film to establish something new. It utilizes every inch of its run time to create an incredible chapter in a larger story line. It is designed to be appreciated in context of every film that came before it in the past 10 years. Infinity War succeeds in telling a jaw-dropping moment in Marvel history by efficiently using every lesson the previous 17 films have learned. It never forgets to stay true to the characters, humor, action, and larger picture of the MCU.

Infinity War compromises where it can, but where it can’t, it doesn’t.

—

By guest writer Emanuel Flores.

Academia

Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

Welcome to the Cinema of Change podcast with Tobias Deml and Robert Rippberger. Cinema of Change is a magazine and community that challenges the conventions of film and its ability to effect change in the world. This episode is an interview with entertainment attorney Mark Litwak called, “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution.”

Mark Litwak is a veteran entertainment attorney. As a Producer’s Representative, he assists filmmakers in arranging financing, marketing and distribution of their films. Litwak has packaged movie projects and served as executive producer on such feature films as “The Proposal,” “Out Of Line,” “Pressure,” and “Diamond Dog.” He has provided legal services or worked as a producer rep on more than 200 feature films.

Litwak’s significance can be see in Disney’s Wreck it Ralph – where the filmmakers decided to name the owner of the arcade which encapsulates the entire plot, “Mr. Litwak”.

Content of this Episode:

- 0:22 – Introduction

- 1:33 – After learning filmmaking, what business pitfalls are common for young filmmakers?

- 5:15 – How is the Film Industry like the Wild West – creatively and in dealmaking?

- 9:11 – How can first-time filmmakers survive the Sharks in Sales and Distribution?

- 12:10 – Reporting the Bad Players: What was your Litwak Filmmakers’ Clearinghouse?

- 15:53 – CAM (Collection Account Management) – how do they help with accountability and fairness for the filmmaker?

- 19:52 – What happened to the Filmmaker’s Clearinghouse?

- 20:40 – Even Ethical Distributors will be out for their own best interest – is that true?

- 22:20 – What criteria do you base your client selection on? What homework should a filmmaker bring to a lawyer?

- 26:44 – How is New Media influencing the market and distribution?

- 34:38 – Can Indie Distribution even compete anymore with vertically integrated SVOD platforms like Hulu and Netflix?

- 39:03 – What progress can be made in the Filmmaker > Sales Agent > Distributor workflow?

- 42:44 – How can a producer put their best foot forward towards a lawyer?

- 45:50 – How can a filmmaker prepare for working with an Entertainment Lawyer?

- 46:46 – What resources exist in the film industry that even the playing field of sales and distribution a bit in favor of the independent filmmaker?

Litwak is also the author of six books: Reel Power, The Struggle for Influence and Success in the New Hollywood (William Morrow, 1986), Courtroom Crusaders (William Morrow, 1989), Dealmaking in the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 1994) (winner of the 1996 Kraszna-Krausz award for best book in the world on the film business), Contracts for the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 3rd Ed. 2012), Litwak’s Multimedia Producer’s Handbook (Silman-James Press, 1998), and Risky Business: Financing and Distributing Independent Film (Silman-James Press, 2004).

He is an adjunct professor at the U.S.C. Gould School of Law where he teaches entertainment law.

Litwak has a B.A. and M.A. degrees from Queens College of the City University of New York. He received his J.D. degree from the University of San Diego in 1977.

We hope you find this conversation interesting and insightful. Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss an episode. Until next time, be the change that you want to see in the world. Then turn it into cinema.

Films

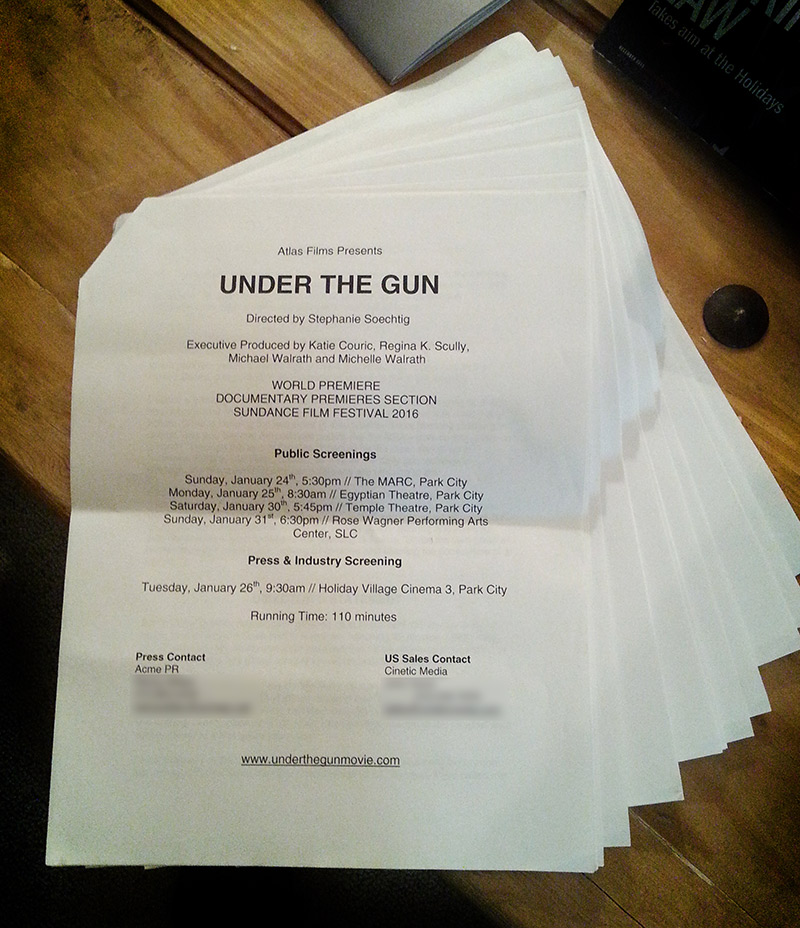

“Under the Gun” – Nonviolent Weapon at Sundance ’16

This is what you get when attending a well prepared documentary press screening: A big packet of information, statistics and insight in the film’s making.

Going to Sundance ’16, I didn’t actually plan on seeing any movies. There were too many exciting events, too many great panels, and a plethora of VR experiences. On an early Tuesday morning, I happen to miss a screening together with a fellow Berkeley journalist, and so we decide to watch some other movie rather than returning to our desks. The movie that we choose coincidentally: “Under the Gun“.

When you go to Press & Industry (P&I) screenings, there’s some empty seats and you’re surrounded by journalists hastily typing on laptops, accessing wordpress layouts and other backend sites for major magazines, all the way to when the film starts and laptops close. Not exactly conducive for “getting in the mood”, but objective and work-oriented.

I had no expectations and had done no research about the film, except for attending a press line with the filmmakers. All I had going for me for this screening was 100+ hours of gun culture debate with friends, TV consumption and online research in the topic, spread out over the past 7 years.

A little review doesn’t remotely do the film’s power any justice; you have to see the film yourself. This article is a discussion of meta-information and potential learning lessons the film gave me.

The Passive Demographic

Every good documentary uses facts and statistics to back up its emotional claims; no different in “Under the Gun”. Out of the data presented in the film, it became apparent to me that there was a political issue of legislative influence in the debate that I hadn’t considered previously. Let me explain:

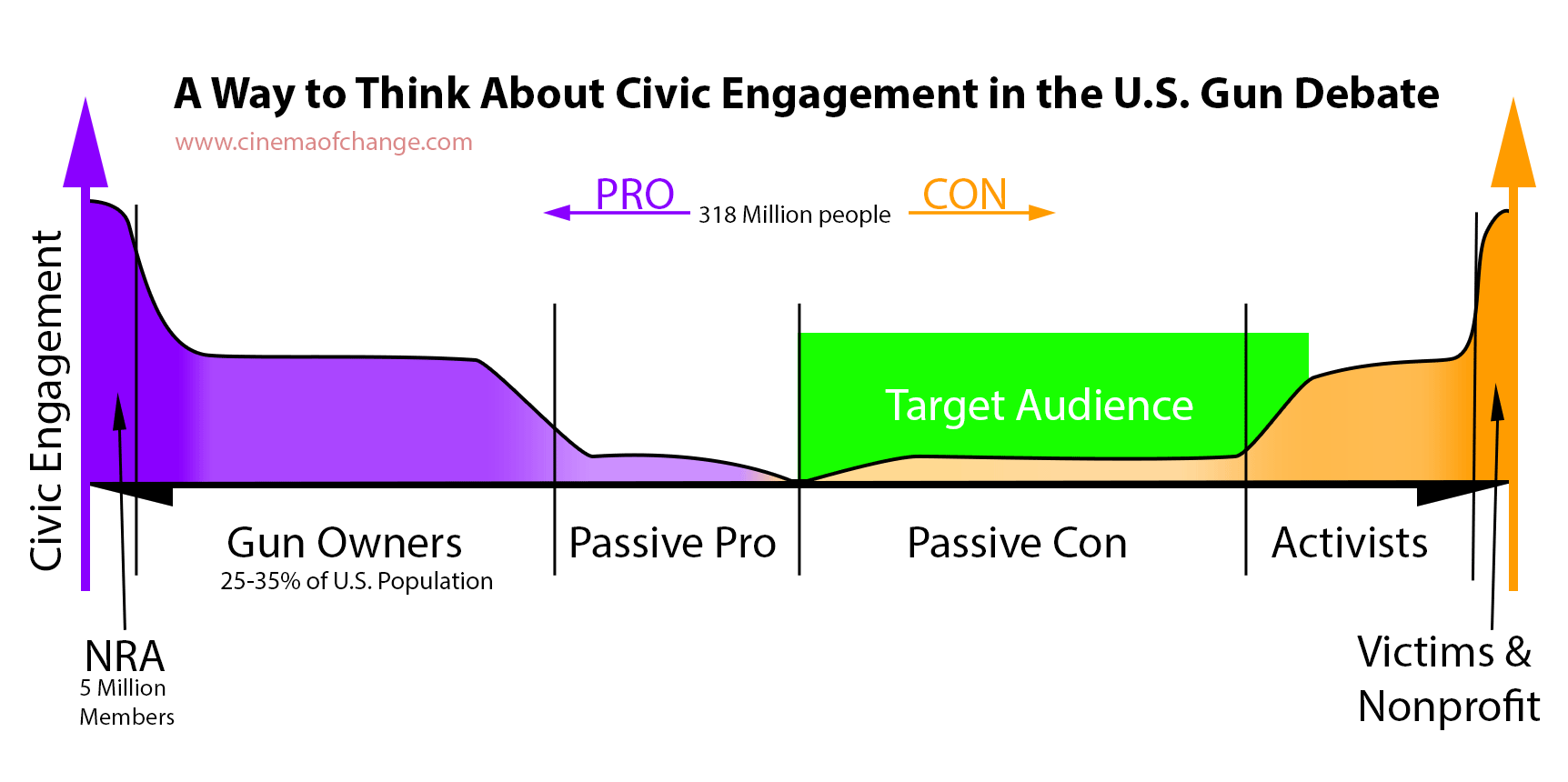

In the gun debate, there are two ends of the opinion spectrum and civic engagement: Pro-Gun and Anti-Gun (Pro and “Con” on the graphic).

Pro-Gun usually means that one supports the wide distribution of guns, believes strongly in the 2nd Amendment, wants more relaxed laws on who can own guns and which/how many guns can be owned by an individual.

Anti-Gun is a position that supports stricter laws (i.e. mandatory background checks in all gun sale situations), has less investment in the 2nd Amendment, wants to limit which and how many guns a private person can own, and generally supports the notion that less guns will make the U.S. a safer country.

What is significant is the political power and passion in civic engagement that these two ends of the spectrum encapsulate.

On the pro-gun end, we mostly have the NRA (National Rifle Association), an extremely powerful nonprofit that has 4 decades of lobbying experience with the federal government, a history going back 144 years (!) and a passionate group of supporters – 5 million gun enthusiasts. In the US, for every 100 people, there are 112 guns. The number of people owning a gun in the U.S. seems to be between 22-30%. Just because you personally don’t own a gun doesn’t mean that your family is without one; 34-43% of people live in an armed household (according to Pew Research), which widely varies by state. The NRA reported a revenue of $227M in 2011 and $347M (!) in 2013.

On the anti-gun end, we have 63 non-profit organizations. Most of the organizations were largely formed as reactions to gun violence such as school shootings and inner city violence or to lobby for stricter gun laws, and have $5M/year or less revenue. A few of the organizations (such as Amnesty International) are international nonprofit behemoths with 7 million+ members and $100M+ of revenue, but cover a wide range of worldwide issues outside of U.S. gun control.

If you think of psychological investment now, you have a 5 million NRA members and some 100 million of casual gun owners and family members. On the other hand, you have around 1-2 million members of the gun-dedicated U.S. nonprofits, and a few million supporters on the behemoth nonprofits. These supporters have some skin in the game, but only if they believe that gun violence could hit them or their communities. It is much easier for the pro-gun group to mobilize their members and supporters to civic engagement (i.e. “they will take your guns away”), and infinitely harder for the anti-gun group to mobilize its passive group of semi-supporters who see it as an issue of someone else (“I feel bad for the victims in Newtown”) .

This is where “Under the Gun” comes in, as far as I can see that: It intervenes with the passive anti-gun group and gives factual insight, emotional connection and holds a mirror to the apathetic audience: Just because it didn’t happen to you personally, doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be actively involved in changing the political landscape.

From the Nazi era to the Milgram experiment, we know that the Bystander Effect is an extremely dangerous form of behavior. And sadly, the crowd of bystanders that lack civic engagement on the anti-gun side is much larger; my speculation is that this is due to lack of personal investment in the cause (as compared to the group of passive gun owners that value their possession and active choices).

Making the film for this demographic is the most effective; instead of trying to convert gun supporters, the film catalyzes passive protest into active civic engagement. I would count myself into this group of apathetic, passive bystanders. The film does a great job at delivering emotional involvement and empathy to the audience, which is the first step to taking action.

EDIT 2/1/2016: My point on target audience selection was speculative-observant. I was lucky to run into the “Under the Gun” producers of the film on a Sundance party, and they didn’t give me a clear answer when I asked about my target audience theory. Attending a Q&A a few days later, on the film’s final SFF16 showing, I turned my head when an audience member asked exactly the target audience question. Soechtig replied:

“Our target audience is the apathetic middle… the demographic that doesn’t vote on gun issues.”

This statement supports my earlier theory of target audience selection. A Collider review criticizes the film for “still missing its target” and that the film “won’t change minds” – in reality though, the reviewer simply missed to properly observe the film’s target audience. A Guardian reviewer described the film as “providing an incentive to get involved in the debate”, which is on point.

My takeaway on this issue was: The problem isn’t pro-gun supporters. They have a well-formulated framework of thought and genuine passion for their cause. The real problem are the passive bystanders that are against guns but do absolutely nothing about it. Dangerously passive bystanders, like myself – who need a wake-up call, and the movie does exactly that.

Social Impact Ratio of Consumption: 100+ Casual Hours < 110 Intensive Minutes

In the past 7 years, I spent a good deal of time debating whether gun policy needs to be changed or not. TV and Internet were sources of information and entertainment. The result? A re-affirmation that I don’t like guns, accompanied with passivity and apathy. The film demonstrates this well by pointing out the pattern that occurs reliably after every mass shooting: Breaking News on TV, a public outcry, public officials taking a position, people dropping off flowers and candles, public grieving, and … then life goes on. Every time, just increasingly depressing.

For me, these 100+ hours of media and debate didn’t do anything; I was treading on the same spot. And then I watched 110 minutes of a powerful, extraordinary documentary. The result? I cried multiple times during the film and didn’t wipe my tears, and told 6 people on my 30 minute trip back home that they absolutely have to see the film. I went straight back to our writing desk and blasted my twitter and facebook, and then did a few hours of research. In the subsequent 2 days, I probably gave another 10-20 people my minute long pitch as to why they should spend their last Saturday at Sundance watching this film. My behavior was observably impacted by the film.

This reaffirmed two theses of mine:

- Films do have a massive power over the individual audience member; not only during their showing, but after as well.

- When it comes to social change media, quality beats quantity. (This curiously goes against the propagandist adage “If you repeat a message often enough, people will believe it”)

To compare casual to intensive engagement with an issue, I propose to establish a (for now, subjective) Impact Ratio of Consumption, where time consumption is variable and social impact stays constant.

In this particular case, the Impact Ratio of Consumption was 60:1 – making “Under the Gun” 60x more effective than CNN, personal discourse and internet research combined. I propose that observing, measuring/estimating and using a ratio system can be very useful for tracking media effectiveness as well as promote films. At this early stage, the Impact Ratio of Consumption seems to have the weakness of being highly subjective, but conceptually it has much potential.

An Emotional Rollercoaster

Just like a good fictional narrative film, “Under the Gun” gave me an emotional ride through highs and lows. I didn’t expect to feel any particular emotion and came into the film quite emotionally sober – yet cried three times during the screening. I considered wiping away the tears, but then decided that I have no need to hide genuine emotion from my fellow journalists. There were moments of elation, moments of deep empathy and thoughtful acts, moments that made me really angry and moments where the entire audience gasped in disbelief.

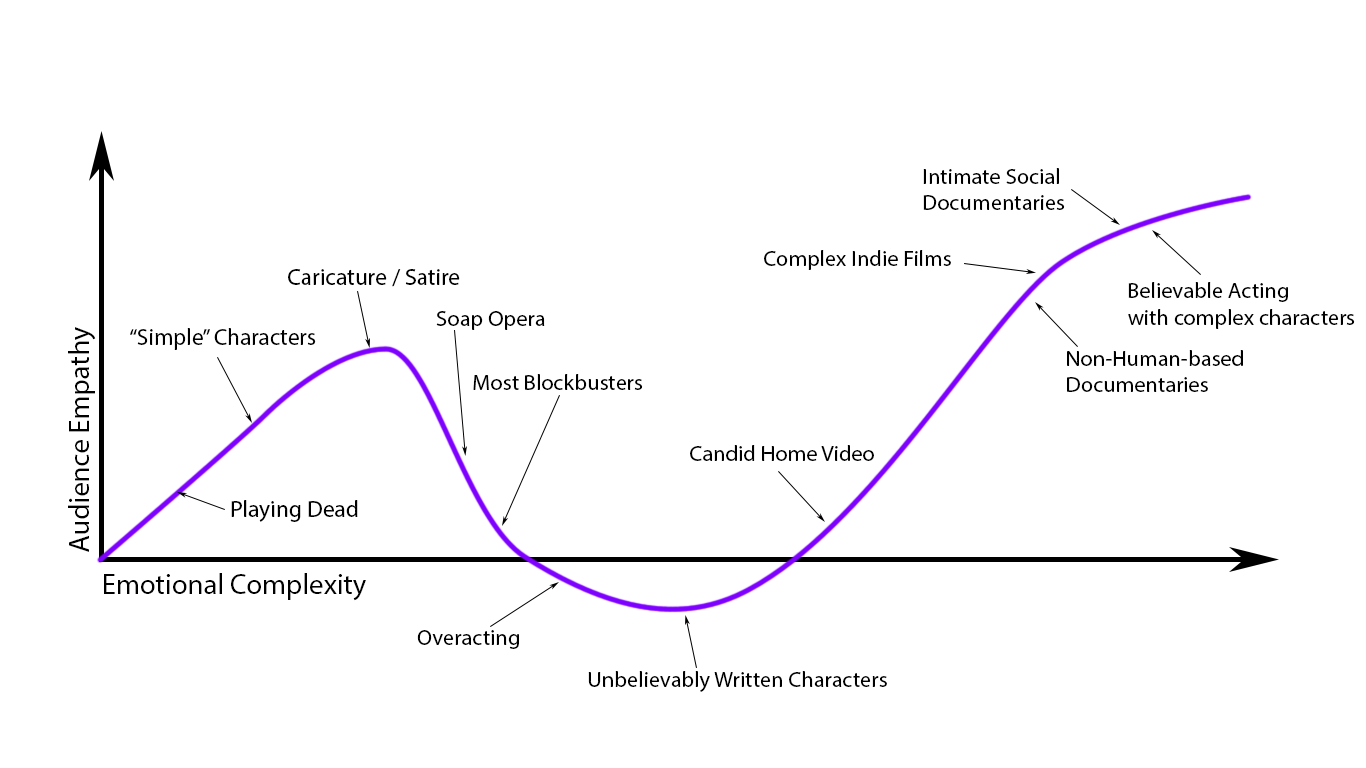

The emotional quality of the film stands for me at the center of its catalytic quality: If it were not for the emotions, I wonder if my wall of apathy could have broken. It is the storyteller’s essential currency – emotional connection to plot and character. Over the past years and with a rise in media literacy, I saw myself care less and less about on-screen characters because I no longer believed their genuine existence. To use a reference from computer graphics, I propose the existence of an Emotional Uncanny Valley. In CGI, the Uncanny Valley refers to the believability of nonexistent characters in animation, going from a stick figure to 2D-Disney to 3D-Pixar to Beowulf and Final Fantasy, to hyperreal CG characters such as Avatar.

A stick figure animation will be perfectly believable, Finding Nemo as well – both of them establish artificial worlds and stylized characters, and are on the rising ledge of believability. Films like Beowulf fail because they pretend to be real yet cannot fool us about the artificial nature of the characters – landing on the bottom the believability Valley.

In Emotion, storytellers can elect to tell a simple story with little emotion or deep stylization, and we will pay attention. Caricatures and silly comedies don’t pretend to be real; they create an artificial world where the laws of physics and human emotion are slightly different. The moment the story and characters become complex and realistic though, we can become highly judgemental to evaluate wether these characters are as real as they pretend to be. We look at decision-making, emotional capacity, reactions and microexpressions. For me, a lot of films fail this judgement test, and I don’t believe the character’s decisionmaking, and subsequently have neither connection to nor care for the character.

With “Under the Gun”, the valley is well crossed; the characters in the film are complex, real people that have such strong and genuine emotions stemming from gun violence that one can do little but empathize with their story. In a way, the audience is given wings to imagine “what if this was me”, and the variety of people (in gender, age and race) portrayed in the film allows identification for most viewers.

At this Sundance, VR has been termed as the “Empathy Machine”. For me, even without VR, “Under the Gun” was one of the most empathy-triggering films I’ve seen.

Update 2/6/2016: Here is the first footage of the film, and an interview with Stephanie Soechtig, the film’s director:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOhncnH9ezA

This article was cross-published at BFF at Sundance.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films