Media Impact

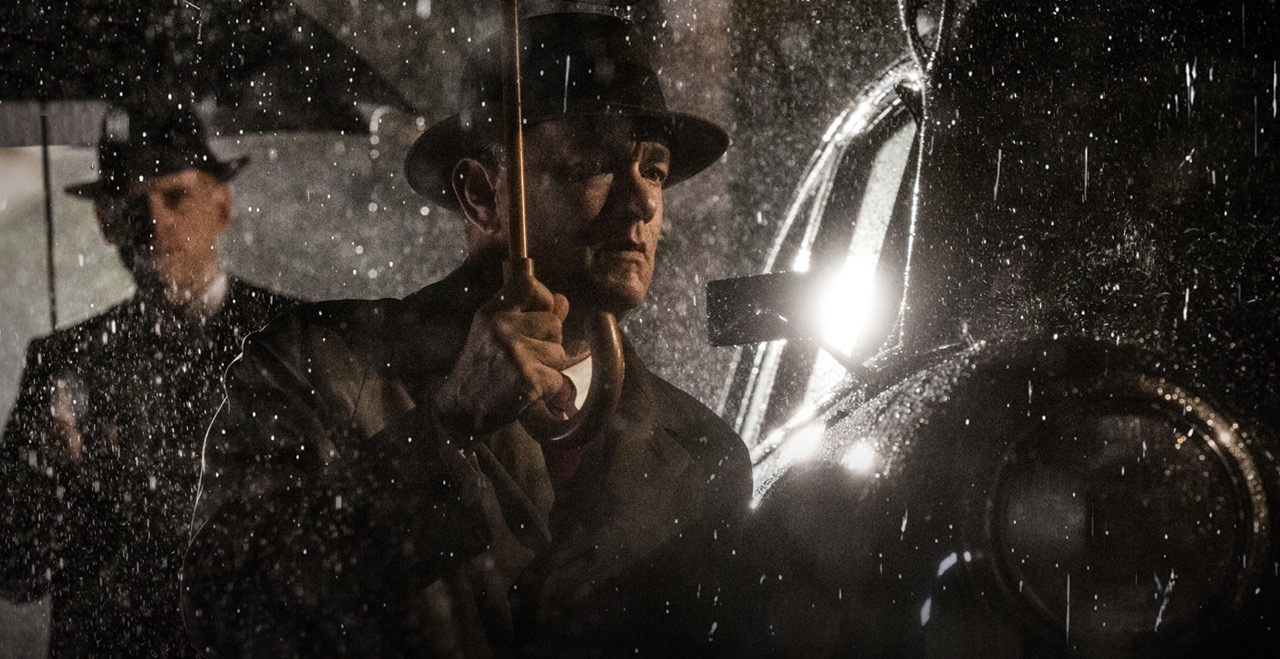

‘Bridge of Spies’: A Thriller of Words, A Drama of Understanding

★★★★★

“Aren’t you worried?”

“Would it help?”

It is exchanges like these, not grueling battle scenes or mercilessly woven plot threads, that become the blood of Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, one of the very best movies of the year. I have long been fatigued by wartime period pieces, so I was shocked by how immediately this one had me in its grip. As soon as it was over, I was ready to see it again.

From its opening image of a man quietly painting his self portrait, the film is a clean slate, slowly revealing itself as a triumph of seemingly incongruous dualities: sprawling in length but briskly felt, epic in scope but nimble in construction, clear in circumstance but morally cloudy. Spielberg, master that he is, keeps it all in the air without ever succumbing to the stealthy flourishes so often associated with spy movies. After all, this is not a film about spying — it is about finding your reflection in the eyes of your enemy and desperately hoping he sees his in yours. In a time when the world is being chewed at the edges by violent fear mongers and extremist groups such as ISIS, a movie like this leaves one wishing naively for the Cold War’s doomed ambience, when not even the threat of worldwide nuclear evisceration could get in the way of two intelligent men trading words over a glass of good scotch.

Tom Hanks stars as James Donovan, an insurance lawyer employed, to his bewilderment, to defend an alleged Soviet spy, Rudolph Abel. It’s clear beyond all doubt that Abel is guilty, but in a way, that’s hardly the point. Donovan, and indeed the film as a whole, views him not as a threat to be scrutinized but as a man deserving of empathy for doing a particularly difficult job. As he points out to a restless jury, Abel is doing the same work here that American men are doing in foreign territory. If we don’t treat him like one of our own citizens, what reason would the Russians have to treat our spy like one of theirs, assuming one gets captured?

And as it would happen, one does get captured, a pilot named Francis Powers flying the just-built U-2 reconnaissance plane to discreetly photograph Soviet ground. In the middle of his mission, Powers is shot down over Berlin and taken prisoner. Suddenly, Donovan’s argument is no longer hypothetical, and Abel becomes the center of a negotiation of trade with Russia, our man for theirs.

The screenplay, assembled by Matt Charman and refined by the Coen brothers, delivers its ideas through the simple actions of strong characters. Equipped with dialog that feels layered rather than deliberate, they make thoughtful statements about the nature of justice, about how someone guilty of heinous crimes should be treated humanely and with dignity, even if you believe they deserve otherwise. To villainize your enemies is to become exactly who they want you to be, and Donovan seems to understand this more than the American people that come to decry him. The best example we can make out of a person is a human one, and if you fail to do that, why should anyone else even try?

A friend of mine once criticized Tom Hanks for having such a distinct presence and charisma that you fail to see anyone beyond the actor. That this could be framed as a genuine criticism continues to confound me. Yes, there are actors who seem to slip into another skin, but others, like Hanks, find enough of themselves in a character that they don’t need to. Perhaps this is why Steven Spielberg is so attracted to him as a collaborator; no matter what story he’s telling or how gargantuan the production, he can always count on Tom to lead him through it with charm, humor, and gentle command. Would Saving Private Ryan be nearly as warm without him? More to the point, who would want it to be?

The true surprise comes in the form of Mark Rylance. Rylance, heartily acclaimed in Britain for stage and television, gives us a version of Rudolph Abel so carefully modulated that you’re kept at a distance without ever feeling as if you’re disconnected from the human behind the mask. He is a character who has slowly calcified over decades, and you’re never sure if what you’re getting is the man himself or the image he projects. It occurred to me about a third of the way through the movie that Abel might not even be conscious of his own limestone demeanor. Maybe that’s why he’s such a good spy.

One-hundred-forty-one minutes. That’s nearly two-and-a-half hours of runtime, and it dissolves like sugar in water. When so many films strain to be great art, Bridge of Spies is first and foremost great entertainment, with everything else following surely behind. The ending is one only a director as seasoned as Steven Spielberg could render so unforgettably: a pulse-pounding climax made from nothing but a few government agents and a snow-laden bridge, where two warring countries stand in pin-drop silence, each side waiting for the other to make the first move.

NOTE: The movie contains a majestically terrible in-joke that I am convinced was intentionally placed there by the filmmakers. The U-2 that features heavily in the story is the namesake of the Irish rock band U2, which seems like nothing until you realize that Eve Hewson, the actress playing James Donavan’s daughter, is also the real-life daughter of the band’s lead singer, Bono. It remains to be seen whether or not Hewson was cast for the sake of this gag, but I thought it was worth mentioning. I was quite proud of myself for catching it.

Spencer Moleda is a freelance writer, script supervisor, and motion picture researcher residing in Los Angeles, California. His experience ranges from reviewing movies to providing creative guidance to fledgling film projects. You can reach him at: spencermoleda@gmail.com

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Media Impact

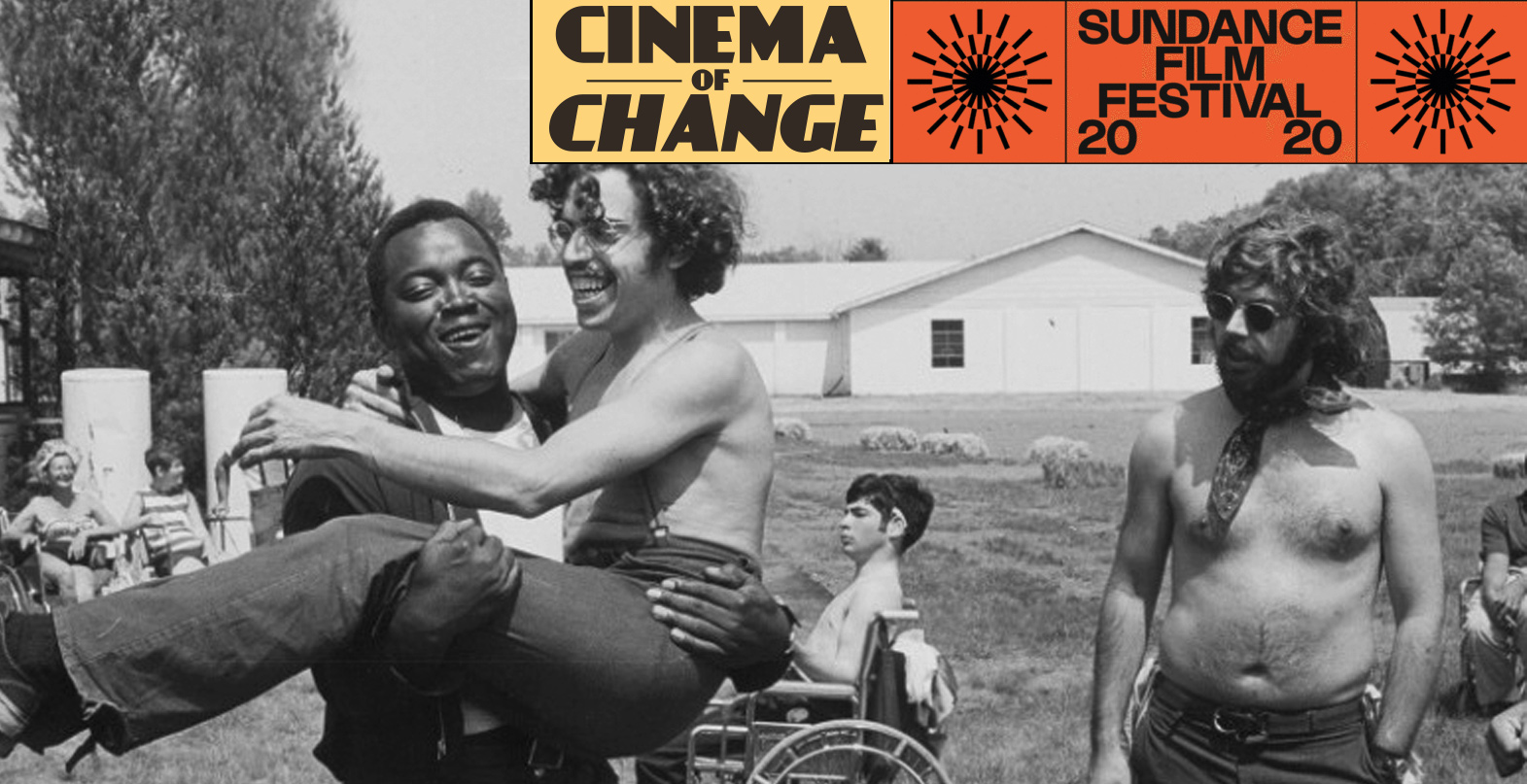

“Crip Camp”: Unified Disability opens Sundance 2020

What happens when a bunch of teenagers go to summer camp in their height of puberty? The wreak havoc, have a great time, try some contraband drugs, and fool around with each other in a virginity-defying quest for adulthood. What happens if these teenagers have Polio, Cerebral Palsy, Down Syndrome, Spina Bifida or MS? The same thing. Just with a lot more wheelchairs involved in the baseball games and make-out sessions.

That’s the world “Crip Camp” introduces us to – for the first 40 minutes of the film, we are immersed in a wonderfully “inappropriate” summer camp Jened in upstate New York. This camp, founded by parents of kids with Cerebral Palsy, operated for nearly 20 years (approx. 1960-1980 with a second 25-year-run in another location until the early 2000s, which isn’t mentioned in the film) and provided an un-sheltered source of freedom for disabled teenagers, and an opportunity for human connection and growth to camp counselors from all over the United States.

Pity VS Profanity

Many films about disability utilize pathos, pity and pain. They are careful in the treatment of their characters and not to step on any toes – a bit like the THR review of the film. And while there is a lot of that in a disabled person’s life – and in many people’s lives regardless of ability – there’s plenty of joy, profanity and profound insights to be had in a film about disability. And, unlike the THR tip-toeing, it’s massively liberating how the film dealt with disability. Not as weakness or fragility, but as a simple fact of life. These are awesome people sharing hilarious and moving insights in what it’s like to be in their shoes.

I might be stepping on toes here, but in my experience with friends and acqinantes with disabilities, none of them want to be linguistically or physically babied or touched with white gloves. There are obvious physical needs that different disabilities come with, but I don’t think it’s productive to be all too sensitive around a person with a disability – it creates the same sort of “separate but equal” impression that sending them off to their own school does. And I think this true equality, making fun of each other and treating each other like we’re on the same level, leads to much more honest relationships.

One of my personal favorites of this level-headed approaches in the film was one of the camp alums recounting a story of his first date in the camp, along the lines: “A camp counselor taught me how to kiss the night before. That was the best physical therapy I’ve ever received. And then the next day, I had my first date with this girl at the camp. She touched my … cock. It was wonderful.” I’ve had similar conversations with quadruplegic friends in my personal life. Many disabled teenagers are perverts just like the rest of us.

These are simply not the things you’d expect if you’re an outsider – but they are the common thread that break assumptions and prejudice. When someone curses on screen, you know you can practically trust them, and there’s no need to put on a pity party. The use of humor is brilliantly applied in Crip Camp to remove barriers – whether it’s barriers between disabled groups, or barriers between the disabled world and the other 80-ish% of the population.

You might say, oh please, we all have disabled people in our lives, and things are much better now. Sure, most of us know a number of people with disabilities. They make up about 20% of the world’s population, practically forming the largest minority on the globe – and it’s hard to avoid getting to know 1 in 5 people. That doesn’t change anything about the fact that there’s still no true equity, and while a lot has happened since the Camp Jened era of the 1960s, 2020 is still full of employment discrimination and false assumptions. As long as you’re not personally affected by birth, disability is easy to ignore. Well, chances are that 1 in 4 of 20-year-olds will become disabled before retirement.

A line in the film profoundly illustrates this invisible divide. Jim LeBrecht, one of the two directors of the film (along Nicole Newnham) and himself having been born with Spina Bifida, recalls his father giving him advice when he was admitted to a public school: “You’ll have to introduce yourself to other kids. You have to approach them and say hello, because they will be afraid to talk to you.”

As filmmakers from all walks of life, the portrayal of people with disabilities on screen is a challenge – not so much in this film because it’s a film made by the community for the community. For those that don’t quite have good access or understanding of disability, RespectAbility’s “Hollywood Disability Toolkit” is a truly comprehensive 50-page guide to do things better. Unfortunately, the guide doesn’t directly recommend to make your disabled characters swear and talk about teenage sexuality – but that doesn’t change anything about the fact that these are powerful tools to disarm your audiences’ potential “fear of the other”. In the end, we’re all just people that can relate to each other’s human experience.

Record Occupations and Missing Footnotes

The film allows us to follow the teenage troublemakers of Camp Janed into their adult lives, where a number of them become political activists, deeply involved in pushing disability rights issues. Crip Camp focuses on one of the campers with Polio, Judy Heumann, who leads a street blockade in 1970s New York for disability rights and then graduates to West Coast activism, gaining continuous steam for the cause, up to the epic mid-point of the film, where hundreds of people with disabilities stage the “504 Sit-In” in the Health, Education and Welfare offices of the Federal Building in San Francisco. Joseph Califano, administrator of the HEW at the time, was unwilling to sign Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was supposed to ban publicly funded discrimination against people with disabilities. Judy and a number of other well-organized community leaders took over the building and made history: The sit-in was the longest occupation of a federal building in the existence of the U.S. (which the film doesn’t quite mention in its historical gravitas). Even Drunk History made an episode on this badass move.

The “Capitol Crawl”, where wheelchair users of all kinds shed their wheelchairs and climbed the non-accessible stairs to the highest symbol of U.S. politics, the capitol.

Up to this point, we’re wrapped up in a beautiful storyline of these teenagers-turned-activists, and appropriately traces the tremendous power the 504 sit-in and Judy Heumann’s delegation trip to Washington had with convincing Califano (after holding candlelight vigils in front of his house and following him to public appearances) to sign 504 into power.

The film then takes a bit of a leap of faith in simplifying the history of the American Disabilities Act of 1990, which followed nearly 17 years later. For the uninitiated, this is the act that put wheelchair ramps into place in all public buildings and gave a lot of protection to people with disabilities, opening up countless new avenues of opportunity – “to assure equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities.” I wondered many times what stars had to align for the disabled communities to have so much unified political power (as they had 30 years ago) to push through such an incredible piece of legislation. On an international level for example, countries like Austria and Japan have had quite pitiful disability laws in comparison to the U.S., usually lagging behind 15-25 years. The ADA was the first act in the world to give such wide support to people with disabilities, and positioned the Bush Senior-era U.S. as the global leader in disability relations.

The film’s narrative centers around direct action and activism like the Capitol Crawl. While these are cinematic moments and films need to simplify history to fit a narrative in a limited amount of time, it gives us a wrong impression of how history happens.

Work like the professional lobbying of Patrisha Wright, or the institutional recommendations of government agencies like the National Council on Disability were instrumental in shifting the tide in favor of the ADA, and the film unfortunately makes no mention of it. I’m not suggesting that the film is under an oscar-speech-style obligation of rattling down all people that should be thanked for the ADA, or that it needs to dive into the complicated politics at the top that made this happen. It would have simply been a nice gesture to have one of the interviewees give a footnote a la “a lot of other things had to work out, outside of our lead character’s activism, to get a historical bill like this put on the table and signed into existence.” As this film can serve as a role model for future activists, it carries some reasonable responsibility to not accidentally further a naive, romantic narrative of “magical activism and easy social change”.

Social change is incredibly difficult, and the people that achieve it study large scale systems, build powerful alliances and invest decades of their lives to utilize the right time in history in order to make a dent in the universe.

United towards Accessibility

This film is about people from all walks of disability and ability coming together to crush an unfair system and fight for accessibility. Together. United. The way it should be. The stories of Crip Camp and the ADA are rather rare exceptions to the usually fractured communities of people with disabilities. As you can imagine, each community has their own interests and doesn’t always see an incentive to support another community. Yet, politically speaking, individual disabilities usually make up single-digit percentages on a global level, but all disabled communities united form a 15-20% front, the “largest minority in the world”, according to the WHO. The more united this front, the more likely things like the ADA can happen again and re-balance the world.

Watch Crip Camp and get inspired. Join or support an organization like RespectAbility that actively works on re-unifying the disability community for political leverage. As humans, we are better than just shunning our fellow humans because of some genetic variation, accident or other circumstance. There’s so much to be gained from creating an equally accessible world for all – and right now, that’s not the case.

Media Impact

HBO’s Chance Morrison on Storytelling and Corporate Social Responsibility

“You are serving up medicine to people. You should be responsible enough to give people directions on how to take that medicine.”

Chance Morrison has worked at HBO for 11 years, holding various positions and currently working in the department for Corporate Social Responsibility.

Chance is a passionate advocate for impactful cinema, serving on the board of Bowery Residents Committee as Junior Board Chairwoman, creating the Ask Chance foundation to provide young women exposure to industry professionals, and earning herself the prestigious Time Warner Richard D. Parsons Award for Community Service in 2017.

She works on impact campaigns for all HBO content, ranging from Sesame Street to Euphoria.

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies7 years ago

Companies7 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact6 years ago

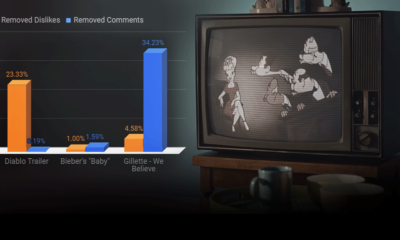

Media Impact6 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine10 years ago

SIE Magazine10 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers10 years ago

Filmmakers10 years agoMirror Mirror: An Exploration of Self-Awareness in Recent Hollywood Films