Academia

Storytelling Superheroes Who Don’t Want to Be

This article is part of the CoC@SXSW2015 series.

Back in March 2015 I attended SXSW in Austin, Texas. After six months of endless work, finally this article sees the light of day.

In one of the panels I visited in the crowded convention center – entitled “Storytelling Superheroes“, the name “Oppenheimer” flashed up on stage. If you ever want to see a deeply traumatizing and tragically beautiful film about genocide, Joshua Oppenheimer is who you should study. Joshua made the groundbreaking 2012 documentary “The Act of Killing” and screened the companion piece “The Look of Silence” at South by Southwest in 2015 – in his hometown of Austin, Texas.

In one of the panels I visited in the crowded convention center – entitled “Storytelling Superheroes“, the name “Oppenheimer” flashed up on stage. If you ever want to see a deeply traumatizing and tragically beautiful film about genocide, Joshua Oppenheimer is who you should study. Joshua made the groundbreaking 2012 documentary “The Act of Killing” and screened the companion piece “The Look of Silence” at South by Southwest in 2015 – in his hometown of Austin, Texas.

To give you a quick impression of both the work that Oppenheimer does and what he’s like in person, here is a 10 minute clip from the Daily Show:

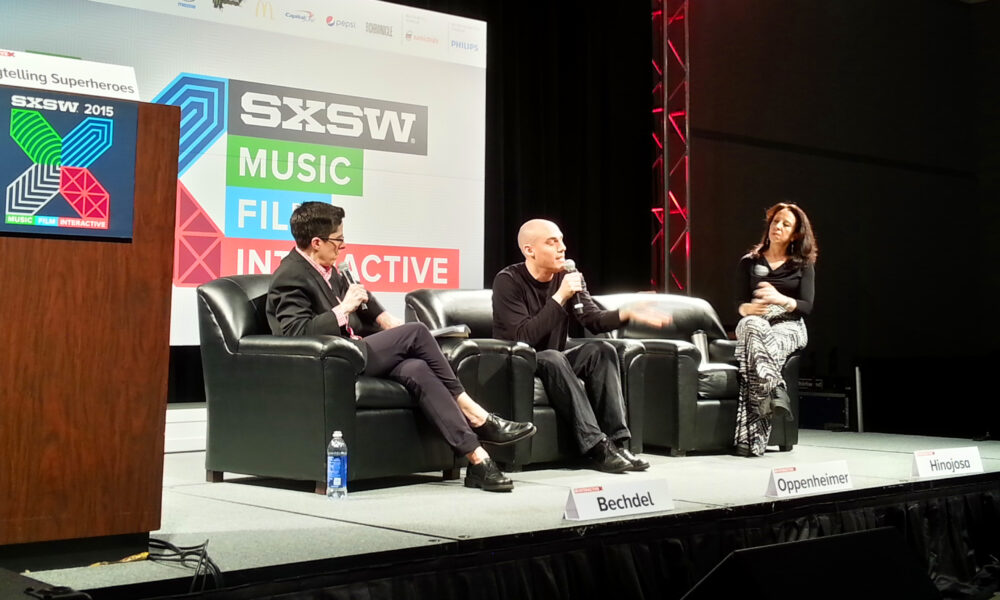

Next to Oppenheimer’s name tag was one that said “Bechdel”. I rummaged through my brain – where did I hear this name before? Could it be … no way – the Bechdel test? A quick check on Wikipedia confirmed: The woman that was reading from her latest book “Fun Home: A Tragicomedy” right in front of me on the podium was that Allison Bechdel who created one of the most accessible ways to understand gender bias in works of fiction.

For those not familiar, a recap will be a wonderful addition to your toolset as both a media maker or media receiver. Apply this test to any given story:

Does a fictional work [1] contain two (named) women, who [2] are talking to each other, about [3] anything else but men.

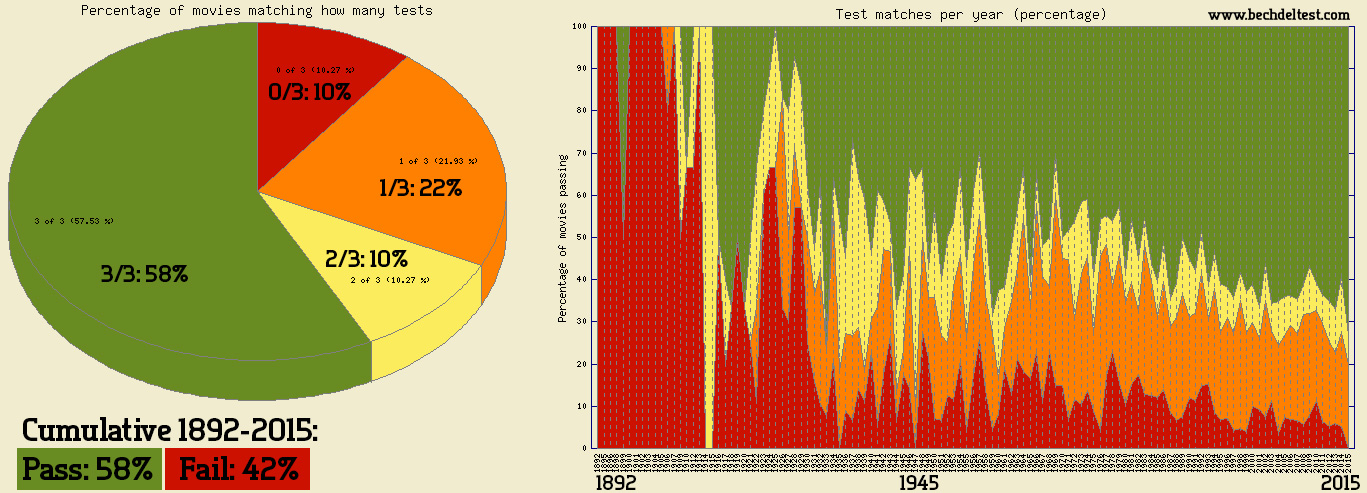

Instinctively, this seemed like a strange question to ask for myself, I never thought about it before I went to Berkeley – but reality looked rather troubling. Bechdeltest.com collects user-created test results (with explanations) and currently stores over 5,000 films – here is a quick statistical breakdown of the current status quo:

As you can see, the trend is heading towards less gender bias, but is still at a rough 60-40 split historically – when really, it should be close to a 95-5 (accounting for films that happen in all-male environments such as male prisons) or even less.

After discovering the test and measuring it against my own films – failing miserably by the way- it shook my up in my storytelling approach, and I try to tell as many other filmmakers about it as possible. I can’t go on making films that are adolescent at best in their self-reflection. I had great intellectual admiration for Bechdel to popularize this test through her comic, and suddenly I got to meet her, unexpectedly, at SXSW2015.

Moderating the panel was Maria Hinojosa, who leads the documentary series “America by the Numbers”, a statistics-oriented PBS show about US-American challenges around ethnicity.

Now that we have the players established, what they said might be more meaningful to you in context to their prior work.

Explorer VS. Storyteller

Oppenheimer believes that a true documentarian is much more of an explorer than a storyteller. His rationale fascinated me – instead of going out to tell the story of someone else, you should take a step back and clear off your preconceived notions of what your subjects are all about. Instead of constructing a story around the facts you think you know, dive deep into the world of your subjects and explore it. Oppenheimer spent years in Indonesia to craft his masterpieces, as a direct participant and active character behind the scenes.

Oppenheimer feels that even during the editorial process, the first two thirds of editing are all about exploration and discovery – finding the “golden nuggets” is more important than to craft a cohesive idea of what you’re looking for in the footage. Essentially, staying completely open-minded to what this film could be until a few months away from picture lock. Only THEN is it appropriate to become the active storyteller that shaves off pieces and funnels the story and characters in a designed fashion. It’s the last third of editorial where you can translate your insight into story.

Oppenheimer feels that even during the editorial process, the first two thirds of editing are all about exploration and discovery – finding the “golden nuggets” is more important than to craft a cohesive idea of what you’re looking for in the footage. Essentially, staying completely open-minded to what this film could be until a few months away from picture lock. Only THEN is it appropriate to become the active storyteller that shaves off pieces and funnels the story and characters in a designed fashion. It’s the last third of editorial where you can translate your insight into story.

The Camera as a Weapon of Truth

In contrast to the “don’t steer your exploration” statement, Oppenheimer’s documentary style is one of “Cinéma Vérité”, where the explorer is a quite active participant in the unfolding of the truth. He observed that people generally like to present an idealized image of themselves in front of a camera – but sometimes that is so obvious that the “hidden truth”, the reasons for the subject’s over-compensating, comes to light.

Oppenheimer goes further than many “fly on the wall” filmmakers would (which you could call “Direct Cinema”), and follows more in the footsteps of Werner Herzog. Herzog has a concept he calls ” Ecstatic Truth“, and the basic tenet of this truth-finding is to influence participants and story elements to show the truth. That truth which the camera could not record were the specific filmmaker not present. If it weren’t for Oppenheimer interviewing and filmmaking for ten (!) years in Indonesia, a lot of the film’s content would actually never have happened.

Oppenheimer explained at the SXSW panel, and I am paraphrasing:

Oppenheimer explained at the SXSW panel, and I am paraphrasing:

I use the camera as bait to make things visible that were not; I create situations and confrontation that didn’t exist before.

That is an important piece of insight for documentary filmmakers – Oppenheimer baited his subjects to engage in the production of the film, out of which arose the production of a theater play, out of which subsequently came a lot of painful reflection for the perpetrators in question. Without Oppenheimer’s presence, they would have probably never experienced these reflections and dealing with their past. But Oppenheimer is not a “colonial fisherman” if you will – he spent an entire decade making two films. He describes these ten years as a “Journey of discovery together with the people in my films” – Oppenheimer sees himself more as a catalyst for unearthing truth rather than an active manipulator.

One of the audience members stood up and told us – deeply moved – that her father had opened up to her after decades of silence about his experience in Indonesia – only because he watched Oppenheimer’s film. That is not only powerful Cinema of Change in effect, that is a new confrontation which would have never occurred were it not for the filmmaker’s indirect involvement.

Oppenheimer refuses to condemn the people in his films as monsters – rather, we as an audience are afraid to see them as people.

Rather than judging, he urges us filmmakers to find the deeper truth in our explorations. We have an obligation to make sense of the wealth of information we unearth and then distill useful information for the rest of the world.

Conflict of Journalistic and Artistic Truth

Towards the end of the panel I asked the three panelists: What when journalistic and artistic truth are in conflict? Who is deciding objectivity?

This is an essential dilemma with filmmakers as well as politicians – which kind of truth should you project out into the world, and how can you hold yourself accountable?

This is an essential dilemma with filmmakers as well as politicians – which kind of truth should you project out into the world, and how can you hold yourself accountable?

The collective answer can be summarized as follows:

Storytelling is a mirror where we recognize ourselves better. Bechdel uses her stories to understand her own deeper truth. Stories have real world effects, they have consequences – so it is imperative to stay accountable as an artist, especially if we bend or select the truth to tell. Hinojosa’s perspective was a quantitative one: Find data on the real world before you start forming your opinion – do not assume, research.

We have to think about it in a bigger picture of capitalism too:

In television for example, the product is not the show, as we might think. It is you, the audience member, that then can be sold for cash to adverisers.

In television for example, the product is not the show, as we might think. It is you, the audience member, that then can be sold for cash to adverisers.

Oppenheimer contended that we keep anesthetizing ourselves through escapist entertainment, and it is our choice of what kind of programs we watch – the Television and Cinema-moguls will follow the audience wherever it goes, since that is the sole resource to cash in on advertisements.

For us artists, there is an importance of doing nothing, of creating spaces and times of silence – in order to find inspiration.

For us artists, there is an importance of doing nothing, of creating spaces and times of silence – in order to find inspiration.

If you’re committed to telling a story, don’t give up. You don’t know where it will end up, and what lives it could change.

And that’s really a basic assumption of Cinema of Change: The stories you tell will inadvertently influence and change someone.

So pursue that dream of authenticity – and keep the vigilance towards your own bias.